Amelia Lang (AL): Thanks for taking the time to talk with me. I know that you have been working on several projects that specifically address migration and families. But, first, I’d like to talk about your series Women’s Work. You started this documentary project after you had your son in 2012 and from looking at the work and reading about it, I get a sense that you knew what you were hoping to photograph. Can you talk a bit about why you started to photograph new mothers within the context of work? What were you looking to document?

Alice Proujansky (AP): I have always identified as a documentary photographer and when I had my son, I struggled to redefine my identity. I had the job of a photographer—work that I am fiercely passionate about—and then I got another job that required a significant amount of time, a completely different skill set and pace, and yet amidst this new role I immediately noticed that it wasn’t valued the same way. There were overwhelming logistics to consider—coordinating daycare schedules and carrying breast pumps to shoots, for example, and financial anxiety. But there has been a lot of conversation about those struggles, so I wanted to document working mothers navigating their entangled identities. We love our children, but parenting is also an intrusion on self and identity and I needed to look at that through work. I started this project, which I consider a personal project, because I wanted to connect with and learn from new mothers who were also navigating that. I am very aware that it’s not a representative project of working moms—there are millions of versions of what that could look like but my hope is that this project represents my transition (through the lives of other women) into working motherhood.

AL: Something I like about your projects is that they are very focused and feel almost like a thesis statement or specific investigation, and the images bolster that narrative as supporting paragraphs or pieces of evidence.

AP: Yes, well, I wanted to be very explicit in this project—to not just photograph moms with new babies but moms who are working and whose identity is intertwined with their work. Clearly, this project also touches on myriad current societal issues—parental leave, childcare, healthcare, cultural norms, stigmas, and so on. There’s a lot that is invisible about balancing work and motherhood and I wanted to make some of the invisible visible as a tool to understand and support other mothers experiencing similar personal, economic, and social issues. Caretakers, across the board, are poorly compensated and I believed that a mother’s work is not seen as labor.

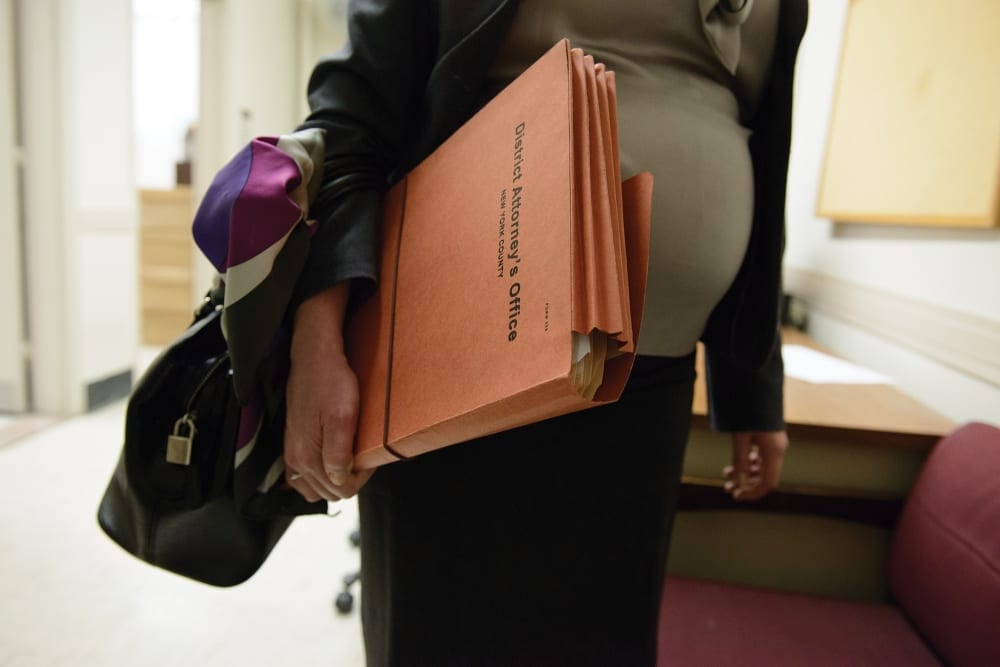

For example, I photographed Jen Carnig. At the time she was Communications Director at the New York Civil Liberties Union and this image was made directly after she led a press conference on the school-to-prison pipeline. I relate to it because it shows the contrast or the behind-the-scenes, yet for many of us this is really mundane and practical and shows the physical side of motherhood and the bodily routines that become the norm. Another woman I photographed was Lucy Lang, an Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan. This image shows her thirty-six-weeks pregnant in a courthouse on trial. She wore many hats with deep identity in each of them, and switches gracefully among them often. This goes back to the idea of transitions—how to leave one identity and way of working and transition to your other role.

AL: This transition between working and then being a mother and continuing to work has gotten more attention recently, à la Ivanka Trump’s book, Women Who Work: Rewriting the Rules for Success. It seems as though there are many conversations happening on this subject.

AP: Yes, it does show that the conversation is happening, but Trump Inc. has co-opted this struggle, draining it of all its complexities. For Ivanka, this seems to be a marketing tool and a way of packaging her identity. It is relatable to the least inclusive, smallest section of women who work. It is a book written for wealthy, educated, white, married, heterosexual women.

AL: Maybe we should re-title her book Wealthy, Educated, White, Married, Heterosexual Women Who Work: Rewriting the Rules for Success

AP: The question for me, and for many women, is not if they are going to work. It is how can I work and be successful, and by successful I mean make meaningful and impactful photographs, and also be successful at the work of being a mother. When I first got pregnant I was reluctant to tell my editors because I didn’t want them to hesitate to hire me. But now, after this project, it has become largely what I am known for. It’s united my life as a photographer and a mother. I am not questioning if I should work, it’s how to work. I think that’s my investigation.

AL: You tend to shoot in black and white and yet Women’s Work is in color. Why did you make that decision?

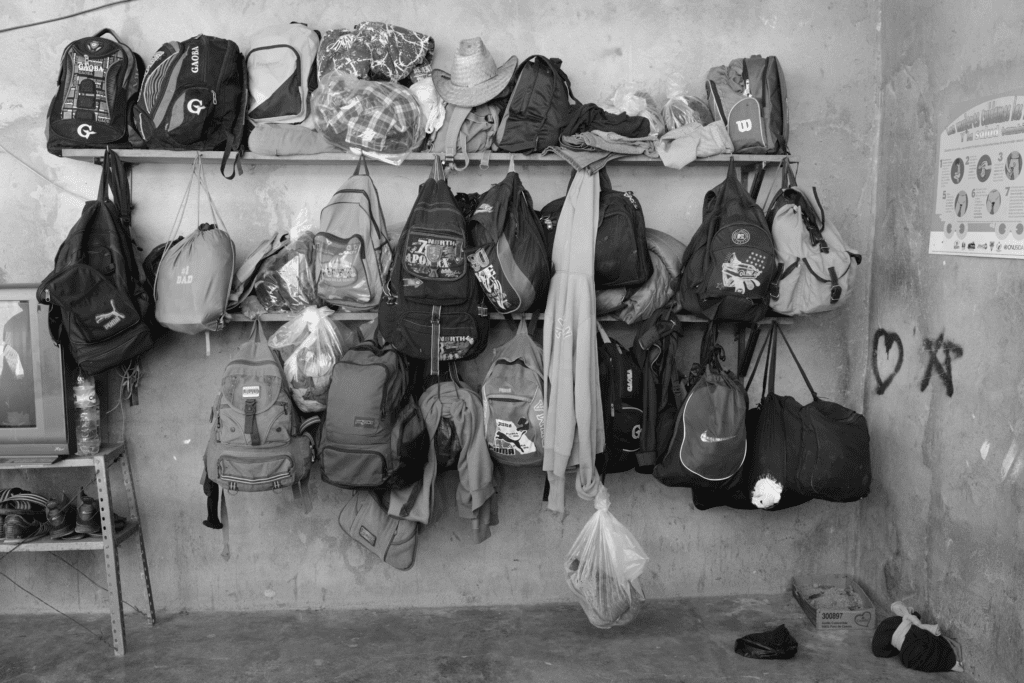

AP: I really love shooting in black and white. The Migrant Families and 24-Hour Daycare series are in black and white. And that was actually out of necessity. The daycare spaces had insane color palettes and I wanted to capture more subtlety and give the viewer space to reinterpret something that looks familiar. I think that you lose the nuance in those colorful rooms. But for the Women’s Work project, I wanted it to feel relatable and immediate, not as removed and thoughtful. I wanted it to look real, chaotic, and immersive.

AL: Why didn’t you photograph yourself?

AP: I have a lot of photographs of myself pregnant, and images of myself giving birth. But I don’t look at them often: I don’t want to replace my memories of giving birth with the images of that experience. I think that speaks to the power of images too—that they can replace our memories. I am not interested in setting up self-portraits. In many ways I did photograph myself, though—it was just through other women who were analogues of pieces of myself.

AL: Migrant Families is a project that you started in December 2016. You knew, based on Trump’s campaign rhetoric, that there was a lot of fear in relation to his stance on the US and Mexican border. Can you talk through how that project changed in these first 100-plus days?

AP: I went to Chiapas, Mexico on a group reporting trip organized by the International Women’s Media Foundation. There were mostly writers, but another photographer as well. As the trip got closer, and formalized travel restrictions and immigration raids became real fears, I realized this is something I wanted to focus on. I have been teaching an eighth grade photo class through Aperture in Sunset Park, Brooklyn where the majority of my students are Latino. There’s always been dialogue about immigration as Obama did not have a great immigration policy, but the rhetoric of the Trump administration shifted the conversation in a very palpable way. It felt different in my classroom. Young people became clearly anxious about the future and the fate of their families. The amount of fear that has been introduced—fear about whether or not a kid’s parents will be home when they get back from school—is so unacceptable. And given all that is going on, I’ve had the advice from various people in the field that you really have to focus on one issue during this period of time. I really believe that with documentary photography there is room to make work that tells stories in an intimate way and that means something to me.

AL: I read an article in Time magazine in late January. It was an opinion piece by Santiago Lyon titled “The Purpose of Photography in a Post-Truth Era.” The article was prompted by the photograph taken of Obama’s inauguration crowd, from above, and was featured side by side to Trump’s inauguration photo. As a photo editor, in 2017, I have been thinking about photography’s role in documenting current events and also making change. You just mentioned intimacy and I think that intimacy is one of those criteria that points to truth. When you create an intimate photograph, a subject is vulnerable. Intimacy, when achieved in a portrait especially, seems to cut away the fat and get to the meat of why and how pictures can slow us down and inspire change.

AP: Yes, I agree. It needs to be more personal than ever. I had an interesting experience of showing this work about migrant families in a classroom and one of the students was able to provide stories for each picture. He could recount context that was not obvious, making it clear that he had been to some of these places, and he used the images to share his immigration story with the other students. I also think that migration and especially deportation are abstract concepts to many people here. We tend to think of economic migrants, usually men, working in agriculture. And that’s a population for sure. But it’s not the only population. I wanted to look at what it was like for families and share images of a more complete story.

AL: You’re in the middle of this project on migrant families. What’s the next step?

AP: I am going to continue photographing the impact of migration on families, first deportees in Tijuana, and then youth in New York. New York was once a final destination for many families but now it has become a liminal space, much like Tijuana, where it doesn’t feel like a fixed home anymore. Young people in immigrant families are so cognizant of what’s going on politically as it will immediately affect them and the people around them. We cannot isolate ourselves. And I hope that this project reminds us of this. I want to make it clear that people are impacted by this rhetoric and these policies.

AL: And this gets into the conversation of impact—what kind of impact do you want to have?

AP: I feel that documentary photography does something. Maybe I am in the Joe Rodriguez camp of true believers, but I think it’s powerful and necessary. Photography may not be the single most effective tool, but teaching and being a documentary photographer and a mother are what I have to contribute and I believe in them.

AL: You’re in an interesting place by teaching through using images. I would guess that using photography in a classroom only reinforces your belief in the power of an image to make change.

AP: I see the importance of images all the time with my students and young people. When I teach, I get to watch people seeing, and that reinforces my confidence that photographs have meaning and it’s not only available to professional photographers. Also, I’ll say that something that I am really interested in, especially after this election, is collaboration. Images can go viral and they are sharable and people like looking at them, but when you partner with a writer or researcher who can unpack policy or legislation or describe how socio-economic dynamics have led to whatever is being pictured, then you are really able to tell a full story. We need visual information as an opener and collaboration to share and contextualize critical stories and information. I want to my images to be used to prompt and complement activists, policy-makers, and journalists.

AL: I am really interested in this idea of matchmaking photographs with the most powerful outlet or platform. There’s great work out there and I often wonder what’s the most effective place to share it. Should a project be a wheat-paste campaign? A billboard in Los Angeles? A gallery show? An Instagram handle? A magazine piece that’s quickly sharable? A photobook? Not to say that any of these options are mutually exclusive, but if we are trying to make change, what outlet will garner that change most effectively?

AP: For the migration project, I think first and foremost is the classroom. Through teaching with Aperture, I have witnessed how impactful images can be in this context, and I really believe that teaching visual literacy will open up the conversation. The Pulitzer Center, for example, gives grants to bring photographers to a classroom. Secondly, the work is news, so I like to see it in newspapers and magazines. And I’ve always believed in books.

AL: I am always heartened to hear that!

AP: Books make you slow down, you have to participate, and the process of making one is way more collaborative than any other form of publishing. Editors and designers help you see your work and present it as a more holistic package. But also, they are references and we go back to them.

AL: Yes, there’s certainly something to be said for printing a physical document to exist in the physical world and take up physical space!

AP: I look at Carnival Strippers by Susan Meiselas all the time. It’s honest, direct, and respectful. Or how Joseph Rodriguez did East Side Stories: Gang Life in East L.A. I think that we have to keep making books so that in twenty years we have them as records. And reminders. Photography books make you leave this world for a minute and reflect. Like when we look at Vietnam Inc. by Philip Jones Griffiths.

AL: This period of time seems like such a critical moment, and I think, in part, because I grew up with so much visual material documenting the Black Panthers and the women’s liberation movement—I learned about the 1960s because of photographs and books with photographs. It seems as though we need to mark or preserve this period of time with the same amount of commitment.

AP: It is a remarkable time and we must document it so that we can learn from it. As a photographer you are in a time and a place but you are always functioning in the past. And part of why I want to make beautiful work is because I want it to last, and yes, document, but also be worth keeping and returning to. Especially now.

AL: Especially now. Alice, thank you for what you do!