Will Steacy describes both his old and new apartments as resembling Hollywood’s stereotypical serial killer lair with newspaper clippings covering every wall. He’s not wrong, but his immaculately-maintained version is simply poetic. He’s not targeting individuals, finding his way to a particular point. If he was, his point would be the various socioeconomic changes in the United States since the post-War boom, attacking every angle of it using every newspaper source possible. I mean that quite literally; he reads each and every major domestic newspaper, every day.

There’s an envelope pinned to one of these studio walls that just says “WILL.” I thought it might be his actual will because he seemed to have so much of his life so deeply and morbidly thought through. It was not. It was just a variation of cutouts of the word “Will.” Apparently they’re not as easy to find in newspaper headlines. In his books, almost every single piece of text is made of clippings. Perhaps a serial killer does live here: they remind me of those classic ransom notes. His book Down These Mean Streets is essentially one massive collage mixing these text clippings, a smattering of other appropriated images, along with his own photographs of urban decay. It’s chaotic, terrifying and psychologically accurate, at least to the intense experience of the struggling working class. It came out right before the 2012 presidential election.

Another book of his, Deadline, which has two printed iterations, is an immense treatise on the decaying newspaper business. It’s a matter that’s close to his heart: his father, grandfather, and his great grandfather all worked in newspapers. In fact, his great, great grandfather, Hiram Young, launched the Evening Dispatch in 1876. Had the industry not changed, he would have worked in the ink-and-paper newspaper business, too.

A year ago I spoke to him and he mentioned he was planning a sequel to Down These Mean Streets to launch before the new inauguration. I wanted to follow him in his process. The sequel didn’t end up materializing, so I went to his studio up in Hudson Heights, Manhattan, to ask why. Little did I know we’d end up seeing a different project he wants to sequel, one that happens to have been his very first photobook.

Romke Hoogwaerts (RH): You were in 8th grade?

Will Steacy (WS): When I did this? Yeah. The assignment was to trail someone’s career and I’ve always been obsessed with the post office. I marvel at the idea of putting something in a mailbox and that it could go somewhere else in the world. I took all these pictures, wrote this essay, laid out the pictures, captioned, blah blah blah, telling the story of what happens in one day at a post office.

RH: Wow. You were already interested in the art of photojournalism? You’re telling the whole story, and captioning in such a classic way. It’s cool!

WS: I was definitely interested in photography. I had a darkroom in my parents’ basement at the time; I want to say almost twenty years ago. Details are hazy. [laughs]

RH: You come from generations of newspapermen, so I’m sure you were around it a lot.

WS: Yeah. I found this in the past year. I dug it up in my parents’ house. It was fun to discover. I’m scanning it all now. I’m sure you’ve heard stories of the financial troubles the post office is having, with drone delivery, and so on. I’m close with my post office here and was thinking about doing a sequel to that. We’ll see what happens.

RH: Speaking of sequels, you were considering doing a sequel of Down These Mean Streets, right?

WS: Yeah.

RH: Where’d you leave off with that?

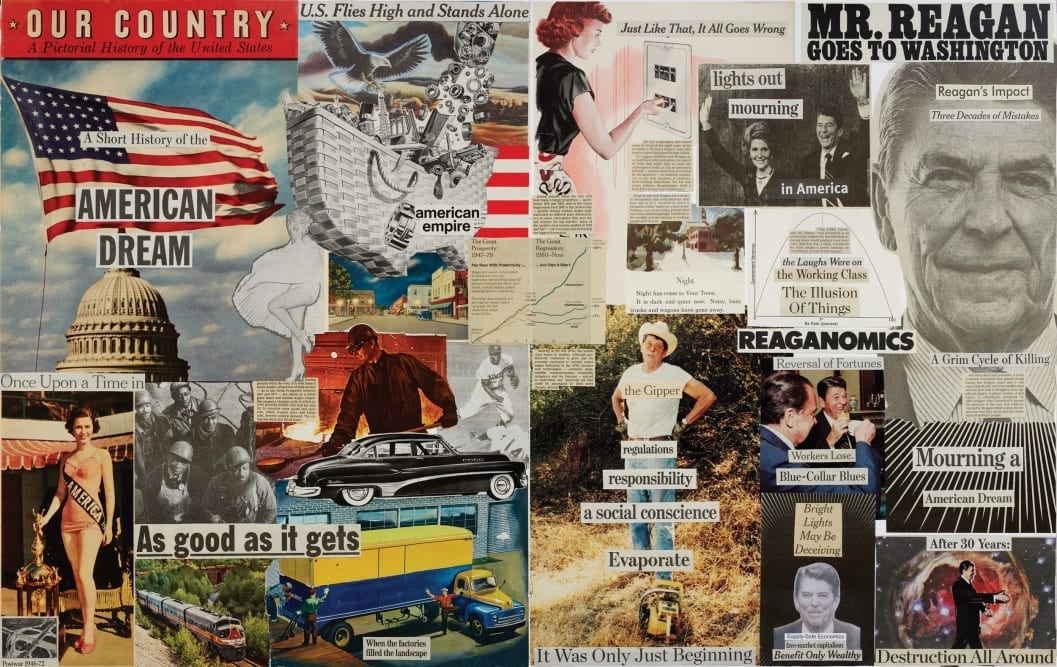

WS: Basically, the Mean Streets project [was published] on the eve of the previous election in 2012. It was addressing what I saw as the decline, the evisceration of the middle class and the American economy, to tell that story from the perspective of those who have been left behind in the ashes of the Great Recession. The project photographically began with me walking around at night with the camera documenting parts of American cities that have been abandoned and neglected. When it came time to make that project a book, I saw those photographs and my own journeys through the night as a metaphor for America today. Here we are as a nation: it’s dark, it’s late, we’re lost. I told that story against the backdrop of what I saw as the three most significant events within the past half century: the post-War manufacturing prosperity from 1947 to, say, 1973; the impact of the Reagan administration’s deregulation by using military spending to boost the economy at the expense of massive cuts in domestic discretionary spending, bridges, roads, etc.; and a shattering of the notion of American invincibility after 9/11. Those three aspects are continuously referenced in telling that story.

Before this election last year, I wanted to continue that story with what I saw as the issues, ironically which neither nominee talked about at all, one of which being the looming pension crisis, the effects of student loan debt which has crippled a generation’s consumer spending power in an economy that is based on consumer spending, which will continue to have limiting growth impacts in terms of annual GDP, a wide range of issues. I should probably tape that list up somewhere.

RH: That list would probably be pretty long.

WS: Yeah, it was quite a long list. I wonder where that is? [searches through his desk] It was like a manifesto, part two. [The first appeared throughout the first Mean Streets book]

Anyway, I made a huge collage, which ended up being the basis for the book. There was a collector who bought that collage. To make it, I spent at least six months getting three or four hours of sleep at night, working non-stop, around the clock; I needed to have it done and the book out before the [2012] election. Without funding to support the project, it’s not feasible.

RH: I’m sure you’ve had a lot of nights like that with the Deadline book, too.

WS: Yeah, [laughs] I’ve had a couple years like that. For the past couple years, from 2012 up until this year, that was how I worked.

RH: Are you still working that way?

WS: No. I’m actually now, after four years of that, getting sleep. I consider myself a sleep deprivation expert. [laughs]

RH: What, are you on polyphasic sleep or something?

WS: The biggest loss of not getting sleep is severe memory loss. After an extended time of really not getting sleep, my memories are [shot]. I used to be able to remember everything. I can’t remember anything anymore. I have a kid now too, so that contributes to it. But in many ways, I don’t even remember making Down These Mean Streets. You know how you get ‘in the zone’ sometimes? I was like that for about six months. I dropped out of the world, doing that. It was a fun time. It was a brutal time too, but looking back at it, I definitely savor the pain and suffering it took to create the work.

RH: You’re working in a different kind of news media, now. What was it like getting used to it?

WS: Well, to go from five, six, seven, however many years it was, to tell one story, to then in one day, telling a dozen, fifteen stories a day…It was a polar opposite change, but in many ways just a further evolution of what I’m doing, in terms of telling stories. For me, photographs and words have always been something that I have found very little contrast—I see them as synonymous mediums. I view what I’m doing now, which is writing all the copy for the NowThis Discover channel on Snapchat, which comes out every day, to me it’s meaningful. I have no idea how many people I was able to reach telling the stories I’ve been telling for the last decade, but to be able to reach a million people every day, felt like a more productive way to get millennials involved in the politics and economics of the world.

WS: When I was in eighth grade, I would come home from school and look at one photobook until dinnertime, looking at fifty pictures in two, three hours. Now, it’s as if we’ve looked at fifty pictures before we’ve had a cup of coffee.

In making the Down These Mean Streets collage and book in 2012, the media environment and newspapers were a completely different being, so to speak, the way stories were written.. And then now, it’s our so-called post-truth, ‘alternative facts’ era, in which people shifted and gravitated towards news consumption habits of accessing information that just reinforces their own ideology and political perspectives.

RH: I’ve heard people say that their Facebook newsfeeds changed entirely when they crossed state lines. What you read online on your own feed, which is supposed to be tailored for you, as you believe, it’s just not the case. It gets manipulated wherever you are. And I remember there was this viral picture a while back that compared all these people on a train reading newspapers, ignoring each other, with all these people on a train on their phones, ignoring each other, saying that times haven’t changed. But it’s entirely different! We went from everyone reading the same thing to everyone reading completely different things.

WS: Exactly. That, to me, is one of the bigger aspects, at least within the Deadline project. Cities and towns, used to have two, three, four newspapers. Within that local news environment, the same people—rich, poor, black, white, male, female, etcetera—who are on opposite ends of the social spectrum, were all unified and bonded by these set of facts. People were exposed to voices and perspectives and views other than their own. Now, that is extinct. There’s actually a story in Deadline that addresses that.

RH: “Thread of Democracy and Civic Fabric of a Community Unravels” by Stephan Salisbury. You commissioned this?

WS: These were written for Deadline. It was so much work, man. Basically I got seventy people to choose whatever they wanted to write about but gave them a list of topics to use as a guide.

RH: I remember you telling me that when you first started the project, you didn’t intend on it being about the decline of the industry.

WS: Correct. When I started the project in 2009, The Inquirer had just reemerged from bankruptcy. I expected the story to go as follows: a newspaper fighting back with its back against the wall and eventually surviving, prospering after an incredibly difficult challenging financial time, juxtaposed with the challenges of the digital news era. As the years went on, the bloodletting got worse and worse, and the layoffs and the buyouts continued, ‘til eventually the newsroom moved out of its iconic “Tower of Truth” building, which it been in since 1925, and moved to a single floor of a former department store several blocks away. It is what it is.