Long before American primetime audiences were introduced to freedom colonies through the ancestral histories of celebrities like Michael Strahan in Dr. Henry Louis Gates’ series, Finding Your Roots, freedom colonies around the world have been documenting, preserving, and sharing their histories—including Houston’s own Freedmen’s Town, also known as The Fourth Ward. Centuries of systemic, institutional, and structural racism have re-envisioned and in many cases erased these places and their important histories. Houston’s Freedmen’s Town was founded in 1866 by American freedmen escaping slavery to create community, self-reliance, and prosperity by banding together family groups and maintaining a safe space from the terrorism of post-Civil War culture. Instead of running north or sharecropping, freedmen created at least five-hundred and fifty-eight such settlements that were established on the ancestral, pre-colonial lands of the Caddo in what is now Texas. As was common in these freedom colonies like Shankleville, Texas where Strahan’s own family settled, the community archived, recorded, documented, and recounted their history since inception, celebrating the sesquicentennial of its founding in 2017 at the annual Homecoming, and the 30-year anniversary of its Historical Society last year in 2018.

These freedom colonies, also known as freedmen’s settlements in the US, had a greater measure of protection from the direct effects of Jim Crow. “Such places were defensive communities, where black property owners had circled the wagons against outsiders—a “fortress without walls,” Sitton and Conrad found. “Freedmen’s settlements were black enclaves that kept to themselves and until the end of Jim Crow, few whites wished—or dared—to live there.” It’s no wonder, then, that mainstream histories often overlook this “more general response of the freedmen’s settlements. In a profile for the non-profit organization Next City, Texas Freedom Colony Project founder, Dr. Andrea Roberts, explains that most freedom colonies made sure to stay hidden from the violent and often deadly racism of white supremacy. “Despite their important role in reconstruction, many Freedom Colonies never sought recognition from state or local government. “Courthouses were a little bit dangerous to show up at in 1890 and declare ‘Hi, I’m an African-American and I own all this land,” she told writer Nina Feldman.

Blacks who acquired land, education, and other markers of wealth, mobility, and prosperity were branded as “uppity” and consistently targeted, as evidenced in the numerous lynchings and violent massacres in places such as Tulsa, Oklahoma, Rosewood, Florida, Slocum, Texas, Colfax, Louisiana, and Elaine, Arkansas. Of course, these are just a few that have become famous due to the horrific use of institutional forces like the National Guard, police departments, and other law enforcement to carry out systemic “white terrorism.”

There are many similar stories and opportunities for preservation organizations like UNESCO, and state and local governments, agencies and societies to extend conservation efforts. Five-thousand freedom colony societies have been identified in the US and in Texas alone, according to Dr. Andrea Roberts’s groundbreaking research at Texas A&M. An untold number of others exist along every pathway of the Western colonial circuit. As systemic, institutional, and structural inequalities from redlining to “urban renewal,” from mining to oil industries, converge over centuries to exponentially replicate the displacement and destruction of these historic colonies of freedom, the necessity of preserving these places and their stories are now more important than ever. With the celebration of Elbert Howze’s work, we continue this important tradition, while honoring those who have come before.

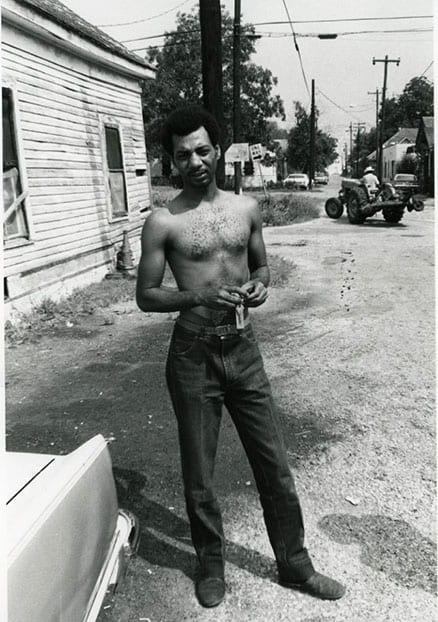

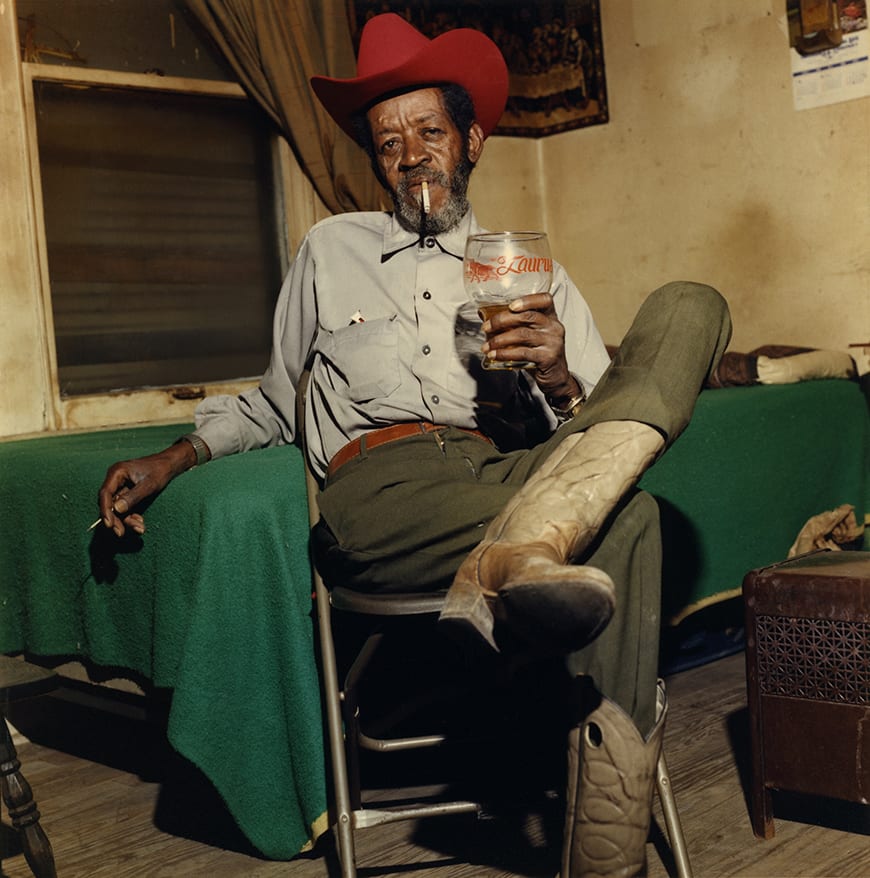

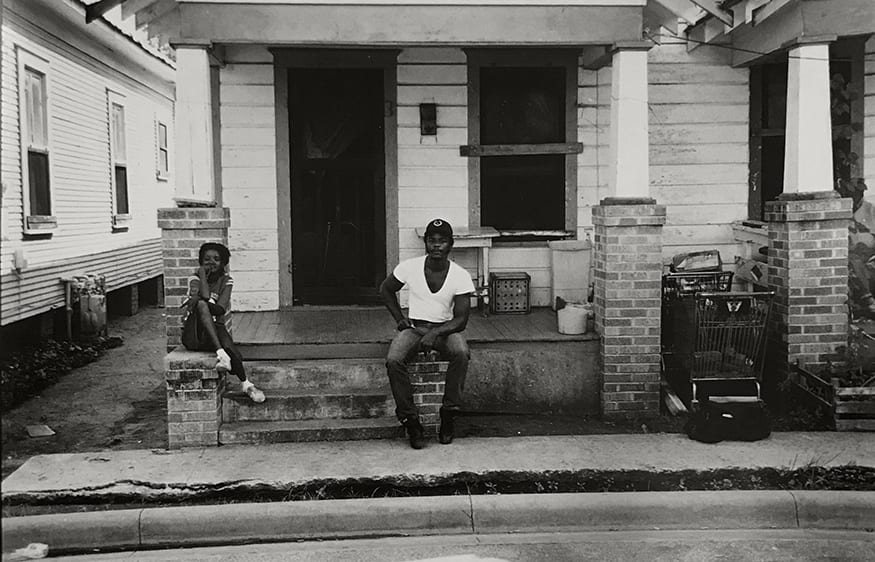

All photographs © Elbert Howze, Motherward, Houston, Texas, 1985