Zora J Murff and I met a few years back in New York. I have since had the pleasure to lecture and exhibit with him on multiple occasions. Last year, we both applied for the Light Work Artist in Residence Program and were both selected. Luckily, we were fast to choose our months and decided to spend our time together this past June. About a week before the residency started, Ashlyn Davis, Executive Director and Curator of Houston Center for Photography, asked if we would conduct this interview. Perfect timing. At times, this will sound like two friends with familiar backgrounds catching up. Some questions go unanswered, some are purposefully concise. All of my queries are in response to the poignant imagery that Zora produces. These conversations occurred while walking sweatily through the streets and during the long thoughtful nights of Syracuse.

Kris Graves: Why did you start making this project in general? This was after you got into grad school, were you already thinking about something like this, or was it just something that came to you after you started to learn more about photography?

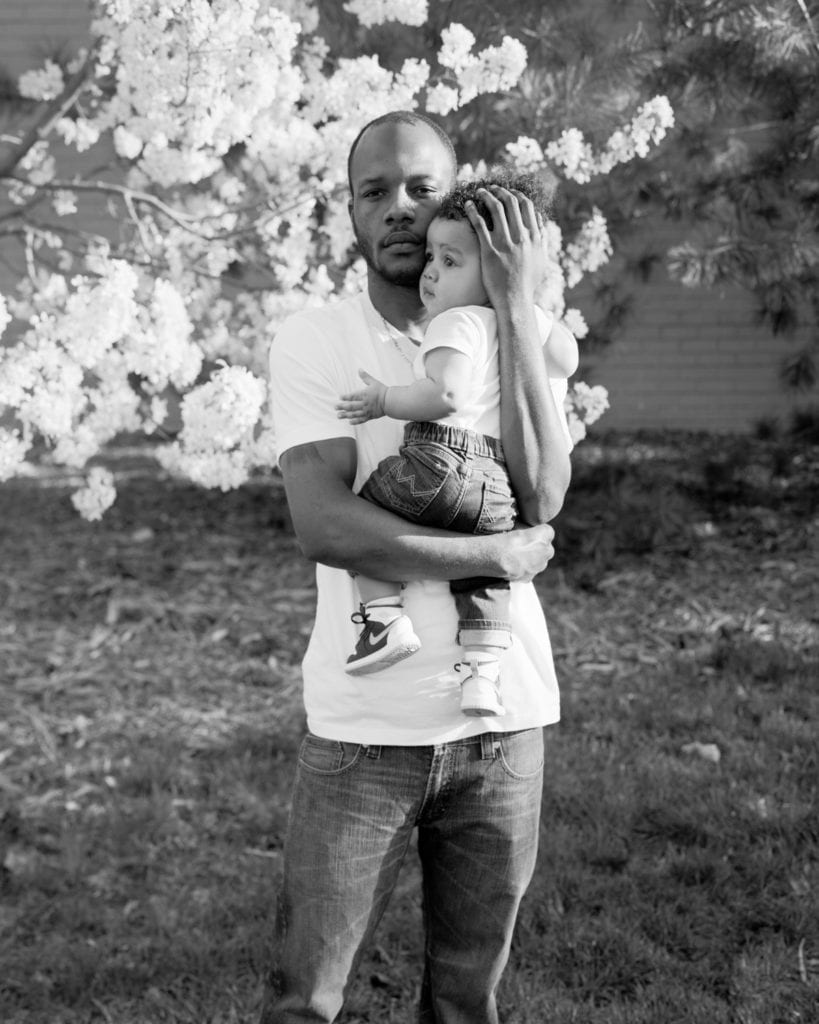

Zora J Murff: I did not go into making the project with a strong intent or clear idea of what the work would be. I came to it gradually, and at a time when I was trying to learn about and understand photography’s many uses. The first time I visited North Omaha was because I dropped a friend off at the airport and decided to drive through the neighborhood rather than get on the interstate. It was the first time since I had begun living in Nebraska that I was in a space where everyone else looked like me. I then noticed the state that the neighborhood was in; it became very clear that it was a place suffering from economic inequality. I wanted to know more about that.

It was through that specific line of inquiry that I found out about redlining. I then began to find these other histories—tragic stories—that helped shape this place and the individuals who lived there. These included the spectacle lynching of Will Brown in 1919, a man murdered extrajudicially because he was accused of raping a white woman; and the police murder of Vivian Strong, a fourteen year old girl who, in 1969, was shot in the back of the head as she was running away from a white police officer.

Between these stories, one interesting phenomenon that I noticed was that concurrent with both of these occurrences were large scale riots. In the documentation of these events—primarily newspapers—the term “race riot” was used to define dissent. The important thing to understand was the reversal of the term in the societal lexicon between 1919 and 1969. In 1919, a “race riot” was often defined as a white mob descending on neighborhoods where people of color live and causing harm. In 1969, a “race riot” was defined when oppressed communities would exorcise all of that hurt, all of those frustrations, all of the bullshit that we were put through. These are often defined by a crucial flash point. In this case, the acquittal of the officer James Loder, who murdered Ms. Strong. I became interested in that relationship, that reversal in terminology and understanding, and started to think about what that means in a larger societal context.

In my first year of grad school, the Chicago Police Department was forced to release the dash-cam footage of the murder of Laquan McDonald in Chicago. I was astounded at the parallels between McDonald, Strong, and Brown. In all of these instances, race played a crucial role in understanding what happened. I started to connect those stories into the history of redlining and began positing redlining as another form of violence, one that is more insidious because it was designed to operate subtly.

KG: What do you mean by that?

ZJM: If one looks back through US history, there is a clear thread between the forms of oppression of black individuals and the evolution of oppression from overt to covert means. Post slavery we see the implementation of black codes, we see Jim Crow laws (including segregation), and now, mass incarceration.

Without segregation, redlining would not have been possible. Redlining was implemented by the federal government, who sent assessors to metropolitan areas to find the financial value of land. One way assessors could determine value was by looking at the racial makeup of neighborhoods. Neighborhoods with large concentrations of people of color are deemed to have “lesser value.” Because they are deemed to have lesser value individuals are discouraged from investing in those areas, and simultaneously, banks would deny loans to people of color. Over time, those areas become economically stressed because those individuals don’t have the resources to invest in their own communities.

KG: How long did it take you to feel comfortable photographing in a place that you’ve never been before?

ZJM: I was immediately comfortable. The best way to describe it was as a feeling of familiarity, a feeling of solidarity because my presence wasn’t questioned, it was welcomed.

KG: How did you know that you had completed your project?

ZJM: I ended the project because I was moving away to start teaching, and I was ready to move on from working on this aspect of it. Looking at my career long-term, I feel my work will continue to elaborate on things like housing, the shaping of communities, etc., but the subject matter of this work was heavy, and I couldn’t continue working with it. My moving provided a natural wrapping up, much like with Corrections. Since both projects were made while I was a student, I knew there was a point when the work would need to end. I’m excited to devote myself to a project for a longer period of time.

KG: That seems like a natural way to conclude.

ZJM: I like the idea of not being so caught up with those boundaries. Being at Light Work for the last month, I’ve had a lot of time to think about what comes next, what that work might look like. I’m also asking myself questions about how I can make something different than I have before. There’s nothing wrong with saying, “for the next six months, I’m going to devote my time to this sculpture that I want to make.” So, during that time, I’m not actively making photographs and reminding myself that is okay.

KG: Do you think it was your first cohesive body of work?

ZJM: I think Corrections was cohesive, there is a lot of naive parts about the work, but still fairly cohesive.

KG: What do you think has changed in your mindset, the way you produce work? Between these two projects it’s only been a few years.

ZJM: It was early, I was a student who barely knew what I was doing, and I was so caught up with trying to figure out when I would become an artist. Would it be when I get this or that degree? When I get a certain job? When I exhibit at a specific place? At that point, the entire time I had been an artist, I had been so caught up in those “rules.” Between the two projects, I just continued to push my boundaries further as my education in art progressed.

KG: In the project, did you feel you were unable to photograph something you wanted to? While you were out there, could you do everything you wanted, or were there still things you wanted to investigate?

ZJM: There are always those sorts of things that happen, but you make the decisions while you are in the midst of it, and you have to make peace with those choices. Ruminating on the what if can drive you crazy. I think if I could go back and make the project again knowing what I know now, I’d probably work with people a little more in-depth. I wonder how the project would change if I found three or four people that I consistently worked with.

KG: But then you become the photojournalist that you do not want to be?

ZJM: Not necessarily, but I think it’s maybe more attached to how deeper my knowledge might be, and thinking how that would manifest itself in the work visually. How would the work change?

KG: While making this project or after, have you been met with skepticism? Have people come up to you and hated this work? Have people had problems with this work?

ZJM: Yes, but that’s an important part about being an artist. I know the work is difficult. It talks about the normalization of violence perpetrated on black individuals and it talks about photography’s—and the photographer’s—relationship to that. Some people have looked at the work and have said they feel they need more information, it is too cerebral, maybe I should add in more writing or factual snippets of text. I feel like that was the way that I did not want to work. I am talking about photography’s objectivity, and that comes from how we see and decide to believe in imagery.

KG: What do you mean by that?

ZJM: Photography is never 100% fact. Objectivity comes from how we understand images, how they are contextualized, how they become politicized. Including a litany of factual information begins to take away from that ambiguity that I wanted to explore.

KG: To make it more of a mass concern?

ZJM: I want the viewer to have to question what they are looking at. Why do the images appear in this specific order? Why are there shifts in scale or emphasis? What are the formal similarities between photographs? What might those similarities signal? I am interested in giving these hints, and the viewer having to dig more deeply than they would if I had just said, “here is this thing, here is this information.”

KG: Who were you studying while you were making this? Were you interested in some specific photographers, or artists, or filmmakers?

ZJM: Some of the first work that really got me to think about subtlety and nuance in work were William Pope L’s Skin Set drawings of text and doodles made on graph paper. He is very clever with wordplay, you read it and think, “yeah, I get that.” And then you think about it a little more and have to read it again, and maybe again, and maybe one more time. Reading and re-reading to try to assemble the message. That level of critical engagement with art was something I had not experienced a lot. So how do I get my viewer invested enough to stick with it?

KG: That is an interesting point. As the world changes around us, making art has become different. The ‘good projects’ are different than they were thirty years ago—we hope. Most of the time, we are just regurgitating the stuff that has existed for thirty to forty years. At some points there are artists that break that mold and they change the lexicon for everyone. As a twenty year old going to college now, they are not learning about Ansel Adams—they are still learning about them as they exist within history, but they are so far from the student’s life that being able to relate to their struggles is very difficult for an eighteen to twenty-two year old. Different than when I was in school, learning about things that happened twenty years ago from then—people like Jan Groover, people that a kid going to school now might not necessarily know or relate to. The world is changing in a way that allows these projects to be understood. If you made this work twenty years ago, people would think, “This is not the problem, why are you showing me these photographs? I cannot tell what’s happening in these photographs. I need to be able to tell.” That was the photojournalistic world. “By photographs alone, I need to be able to tell what’s happening.” So, I think that is also what is changing. That is what I see in the work; that is why it works.

Have you seen a change in the photography world while working on this project? Even as you began the work, was there a theme in photography that you felt was happening? It might not have been exactly what was happening, but how you felt about photography. Then and now.

ZJM: I am trying to think of what photobooks I was buying at that time…

KG: Five years ago?

ZJM: I felt like I had a lot to learn. About myself, about the world, about art. I still feel the same today, still very curious and working to find the answers…I think I lost the question here.

KG: That is fine—these questions are made to get lost in. I was asking what artists were guiding your work.

ZJM: When I was leaving Iowa, I bought a copy of Daniel Shea’s Blisner, IL. I didn’t understand the work at first. I looked at it repeatedly, trying to figure out what he was trying to accomplish. While confused, I was also intrigued by the work. My own work at the time was really serial and straightforward. When I saw Blisner, it seemed very abstract and complex. That was something I wanted to try to see if I could do, because it was something I didn’t know how to do.

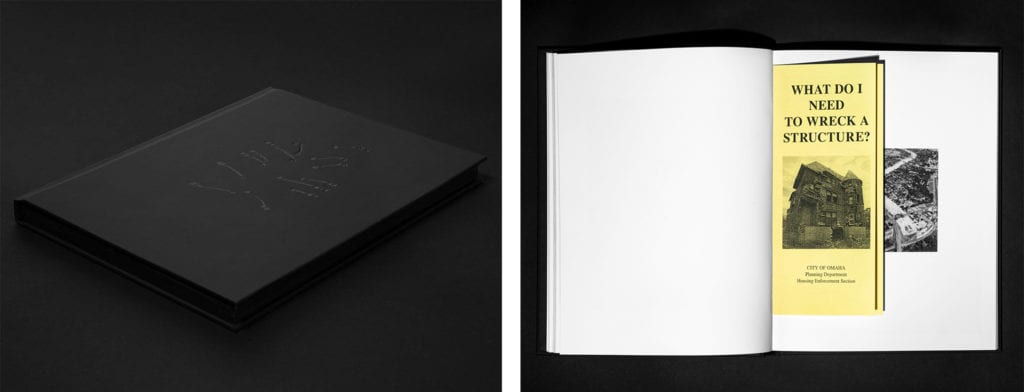

KG: Let’s talk about the book. It’s beautiful. You should be applying for everything. Who cares if you win things or not, that’s not why we do it. What are the technical specs of this book?

ZJM: It is 7.25 x 9 inches, vertical, one hundred pages, matte stock paper with site specific varnish. There are also inserts, tipped in pages. We finished the book with a painted black fore-edge, black faux leather cloth and an embossed design on the front and back.

KG: Who is the publisher?

ZJM: Dais Books, a new imprint by a fellow photographer, Shawn Bush.

KG: How did you meet Shawn?

ZJM: Shawn became familiar with my work through the Lenscratch Student Prize. He was a juror the year that I won. He reached out not too long after that to see if I was interested in publishing my work with his help. His model for his imprint is to provide funding to artists to produce a limited run, hand constructed book. The process is deeply collaborative, he and I spoke on the phone almost every week between November and now. He was very up front with me that this wouldn’t be a mass-produced book and that I would have a heavy hand in the book’s design. It was important for me to make this book exactly how I saw it in my mind, so working with him was definitely the right choice.

KG: When did you start working on it?

ZJM: We started working on it in November of 2018.

KG: And now it’s June 2019 – When does the book get released?

ZJM: The book will be released for pre-order this July. Shawn farms out the printing of the text block, be he will be—in my book, for instance—tipping in all of the end pages, sewing in all the inserts, making all of the covers, clamshell boxes for the special edition, so it is a lot of work on his end, but the investment should be well worth it. There is a hardcover version and special edition. The special edition is the hardcover book in a clamshell box, and it comes with an insert of a redlining map from Omaha. The hardcover is $70, and the special edition is $150.

KG: Cool – ok, a few last things. Close your eyes. Who on Instagram, what photographers work do you want to see when you open Instagram first?

ZJM: I would have to say D’Angelo Williams.

KG: He’s amazing. His work always comes slow.

ZJM: Yeah. It’s always a great moment when it pops up.

KG: Any advice to the young photographer?

ZJM: Keep trying. Keep making things. Keep trying new things. Keep failing. Keep trying.