“When we got to Richmond, my father took me on a tour of the city…He took me first to the area of the city where he had lived and that has since become Interstate 95. For thirty minutes we stood by the highway, cars barreling by, as he perused the few surviving landmarks. ‘We used to live over there somewhere,’ he said, frowning and pointing to a spot in the northbound, center lane. ‘Must’ve been somewhere over there, near that overpass.’”

—Steven Gregory, author

Black Corona: Race and the Politics

of Place in an Urban Community

My first introduction to gentrification and urban renewal came by way of the last course I would take in graduate school, “Social and Ethnic Issues in Historic Preservation,” taught by the brilliant Dr. Mary Corbin Sies. Historic Lakeland was an all-Black community established in the 1890s, situated directly across Rt. 1 from The University of Maryland, College Park. Lakeland served as our case study for the course, an intensive community study largely informed by the participation of its descendant community. What we learned that semester is that this once storied, thriving community had been decimated by the expansion of the Green Line subway route of METRO, the Washington, DC-area transit system. We learned that declarations of perfectly good dwellings as “uninhabitable” resulted in their being condemned and subsequently snatched by eminent domain, and these tactics were used to force a mass exodus of generations of Black families from the community. One can imagine, given the subject matter, that we were forced to grapple with some very challenging realities over the course of the semester; however, there is one week in particular that will forever stand out. The class embarked on a walking tour of the Lakeland community, led by Dr. Joanne Braxton, a Lakeland descendant. Walking from Embry AME Church, one of two remaining churches in the community, past the original elementary school building, we arrived at Lake Artemesia and gathered around a plaque that detailed the community’s founding. It was at this spot—serene and picturesque, with its mature trees, park benches and running trail—that Dr. Braxton pointed toward the lake’s center and shared that the location of her family home was just about there. Somewhere, over there.

Richmond, Chicago, New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Washington, DC—nearly all of the major metropolitan centers of this country share in this ubiquitous story of gentrification, urban renewal, and the disruption to and displacement of predominantly Black communities. Texas is hardly exempt from this narrative, wherein the state’s major cities share in the same refrain. Right here in Houston, the soon-to-be third largest city in the nation, the march toward “progress” has resulted in the irrevocable erasure of much of the Fourth Ward, the city’s first settlement of free Blacks that dates back to 1865. Historian Tyina Steptoe points to East Texas, Galveston, and the “Sugar Bowl”—the area south of Houston which encompasses Fort Bend, Brazoria, Wharton and Matagorda counties—as origin points for the formerly enslaved African descendants who would settle in Houston as free men and women, having learned of their freedom two years after Lincoln signed the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation into law. Fourth Ward, with its swampy conditions and prevalent flooding, proved to be the land least desirable to whites, making it one of the only areas in the city where Blacks could settle—and settle they did. Steptoe suggests that by 1870, a mere five years after their arrival, Blacks accounted for forty percent of the population. Freedmen’s Town quickly became the social, cultural and political hub of Black Houston. Homes were built; Antioch Baptist and Trinity Methodist churches were established; businesses were started; mutual aid groups were created; and in 1870, with the aid of abolitionists, the Gregory Institute was founded, becoming the first school for free Black children in the city of Houston.

There would be other Black settlements and communities to come—Pleasantville, Independence Heights, the Third and Fifth Wards, Acres Homes; but Freedmen’s Town/Fourth Ward, with its close proximity to Downtown Houston, was very much the epicenter of Black life in the city. Pulling data from The Red Book of Houston, the index of “Houston’s colored population” first published in 1915, Patricia Pando writes.

One enterprise was not present on San Felipe Road or in any of the wards other than the Fourth. Professionals. Black professionals gathered to do business in sight of Market Square, primarily in the 400 blocks of Milam and Travis, with some on connecting Prairie. Of the seven physicians including the well-known B. J. Covington, all but one practiced there. C.A. George had his dental office on Milam, while J.L. Cockrell did his drilling on Travis. Lawyers and notaries joined in, as did insurance companies, a contractor and builder, a job-printer/publisher, and several realtors.

Pharmacists, tailors, grocers, and barbers all worked diligently to supply this thriving community with necessary services and daily conveniences. As Blacks were denied access to the utilities and public works the city provided, brick masons hand-laid bricks to not only create streets but to elevate the physical boundaries of the area. To this day, a portion of the brick streets remain, and amazingly, Freedmen’s Town rarely floods.

Research shows that while the population of Fourth Ward was overwhelmingly Black, home ownership was not, a fact that would ultimately factor in its demise. The majority of homes in the area were leased to Black residents by Italian and German owners or landlords. This reality, coupled with the fact that Fourth Ward was physically landlocked by other entities, limited the creation of new development necessary to sustain the community by both maintaining the old and attracting the new. As early as the 1920s, Fourth Ward’s Black population had begun its slow and steady decline. Historian Tomiko Meeks suggests that by the 1930s, the area was already on the radar of city and federally-funded redevelopment programs. The early 1940s saw the erection of San Felipe Courts, a public housing project built and funded by the Federal Housing Administration for white World War II veterans, initiating the decades-long extraction of land and housing from Black residents through eminent domain. After decades of increasing development, demolition, Black flight and neglect, Freedman’s Town would again become a target in the 1970s. Meeks points out that as it was perfectly situated between River Oaks, Montrose and Downtown, Fourth Ward was deemed a prime location to provide more living space for citizens who worked Downtown. A master plan was created to demolish dilapidated homes and sell the land to developers, putting into motion a now decades-long battle for the preservation of this historic community. Martha Whiting, granddaughter of Jack Yates, crusaded relentlessly to save Antioch, which had been siphoned off from the remaining community by the Pierce Elevated and the expansion of Interstate 45. Long-time residents like Gladys House and Lenwood Johnson became activists for their beloved Freedmen’s Town, mobilizing to get the services and capital that had been denied the area for decades.

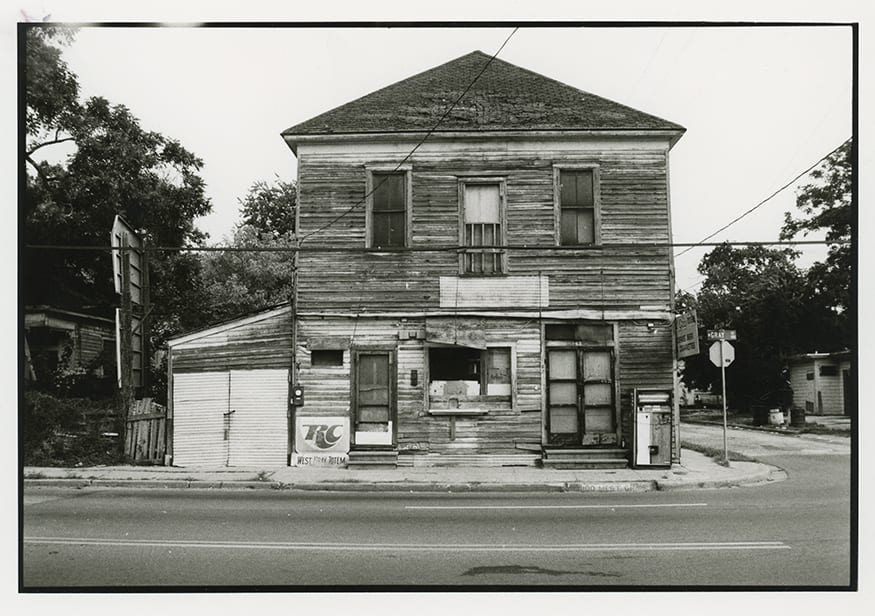

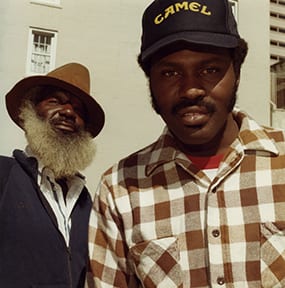

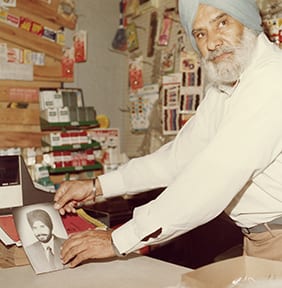

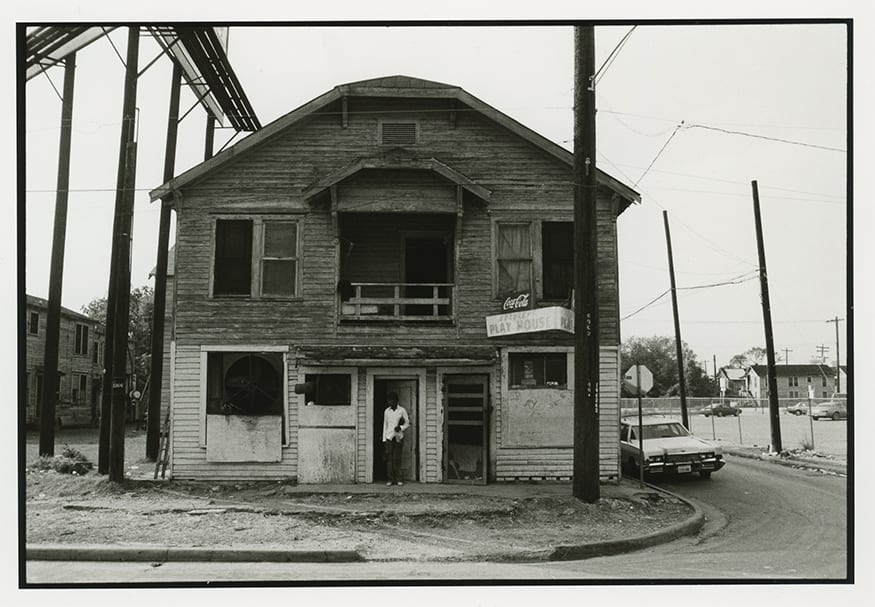

Elbert Howze focused his lens on Fourth Ward in the 1980s. By that time, the battle for the soul of the community had long been underway, and the physical landscape bore witness to the fight. However, Howze’s work isn’t about the built environment, bruised and fractured as it was. He plainly and succinctly admonishes the viewer that his work is about the vibrant, beautiful cultural landscape that the people of the community create. In an introduction to his collection of images, Howze writes,

Today, the area consists of street after street of delapidated [sic] and crumbling structures which are rotting away around the people who occupy them. The enclosed photographs are not about the physical neighborhood of Fourth Ward, but rather the people who live there. Prosperity is no longer monetarily evident, but there exists a wealth of history and pride in this area. The Fourth Ward is more than just a place: it is a state of mind, but more importantly, it is people.

And so, it is my hope that everyone who views the Elbert Howze collection does so with his words ever-present and at the fore; that we, his audience, challenge ourselves by not using his work to serve as confirmation of the many narratives of pathology surrounding disempowered Black communities. Instead, may we honor Howze’s deliberate efforts to show the abundance of life in Houston’s Mother Ward, a “somewhere over there” where community, family and history converge.

All photographs © Elbert Howze, Motherward, Houston, Texas, 1985