Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, resulted in the incarceration of one hundred and ten thousand Japanese Americans in ten concentration camps. The camps were all constructed at uninhabitable isolated terrain sites scattered from Arkansas to California. Two thirds of these prisoners were American Citizens, born, raised, educated, and loyal to the USA. Their alleged crime was looking like the “enemy” sensationalized and espoused by “Yellow Peril” press and politicians.

The late Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani was born on August 19, 1945, in Chicago. It was in Chicago where his parents John Shuzo Nagatani and Diane Yoshiye Yoshimura, both second generation Japanese American citizens, met. His parents took advantage of an early release program to contribute to the war effort, found work sponsors in Chicago, left their families in camp (Nagatani’s in Jerome, Arkansas; and Yoshimura family in Manzanar, California), and ventured out to an America still harboring resentment to humans with Asian features. It was within this era that Patrick was conceived.

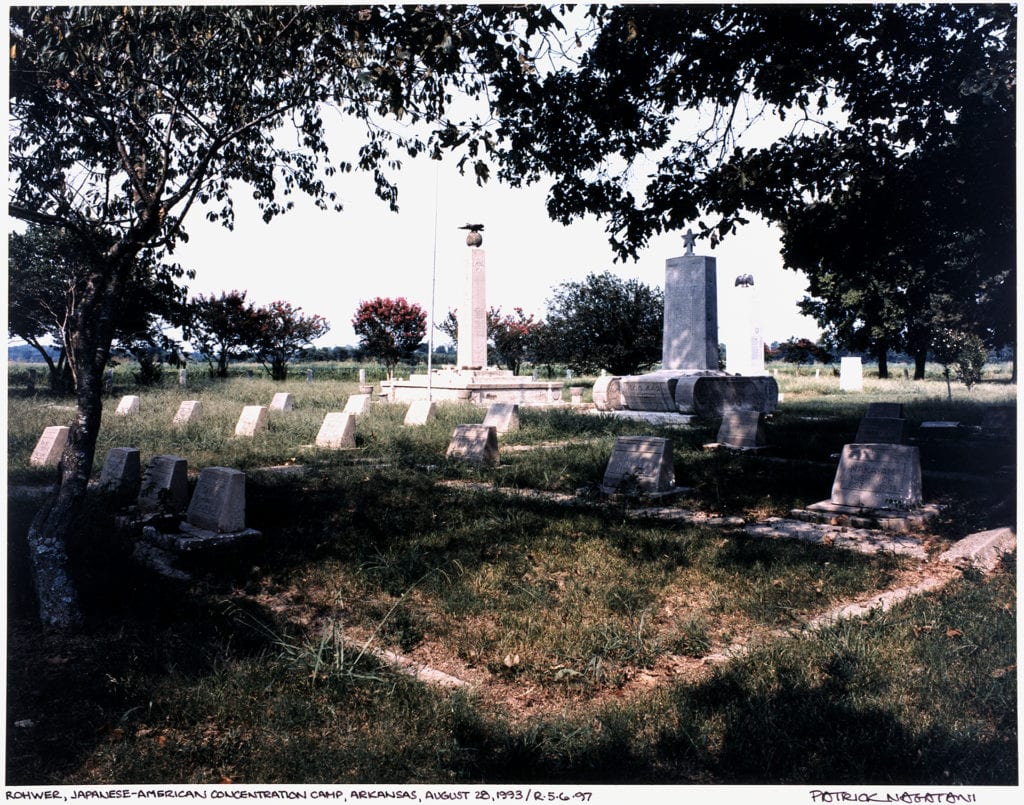

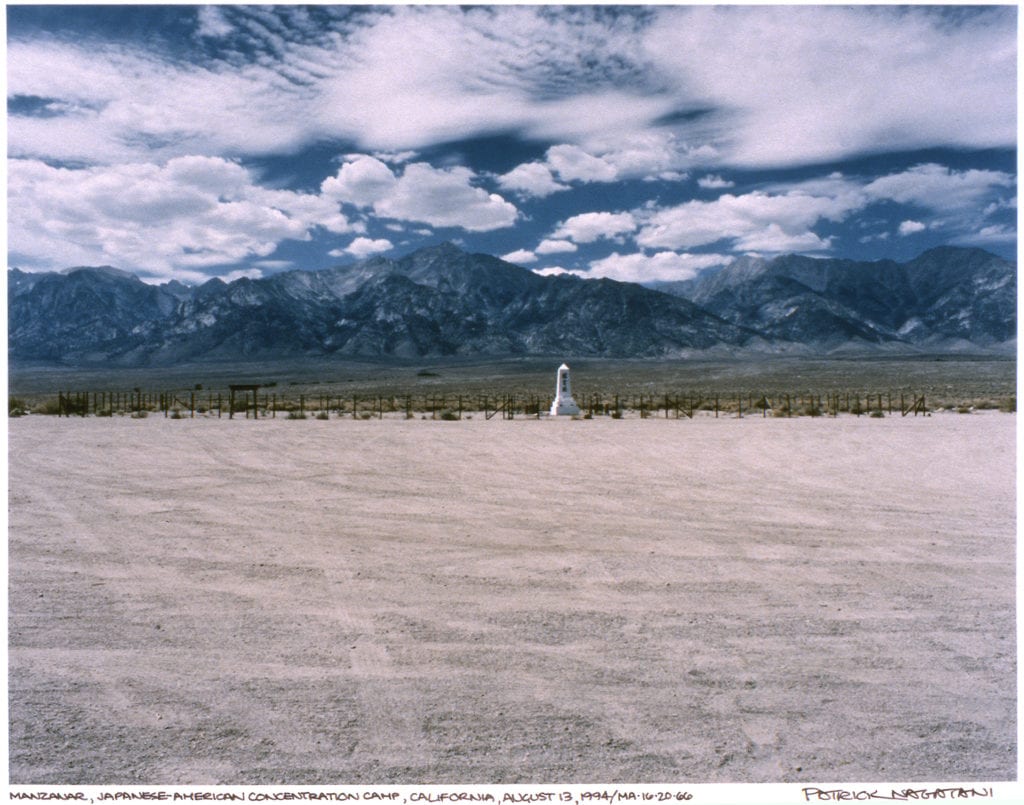

Later in life, photographic artist Nagatani made a personal pilgrimage to photo all ten camps. The terrains at these locations remained isolated and desolate, as if untouched by time. A few of the locations identified a previous camp site by a token” plaque. The most startling reminder that Japanese Americans were confined at a Concentration Camp was a Monument constructed in the gravesite at Manzanar, the monuments inscription reads, “Memorial Tower.”

To prepare for his camp photographic journey, Nagatani spoke with many elders who had endured the camp experience. While most were initially hesitant or reluctant to talk about this traumatic chapter in their lives, during the interview process they expressed vulnerable suppressed emotions. Through these interviews, Nagatani grasped a more complete understanding of the Japanese concept “Shikata ga nai.” Loosely translated it means, “endure, don’t complain, it cannot be helped.”

They shared with Nagatani personal life stories of how they managed to make the best of being confined with ten thousand others within a concentrated area, encircled by barbed wire, and “protected” by gun towers with weapons pointed and aimed “inward.”

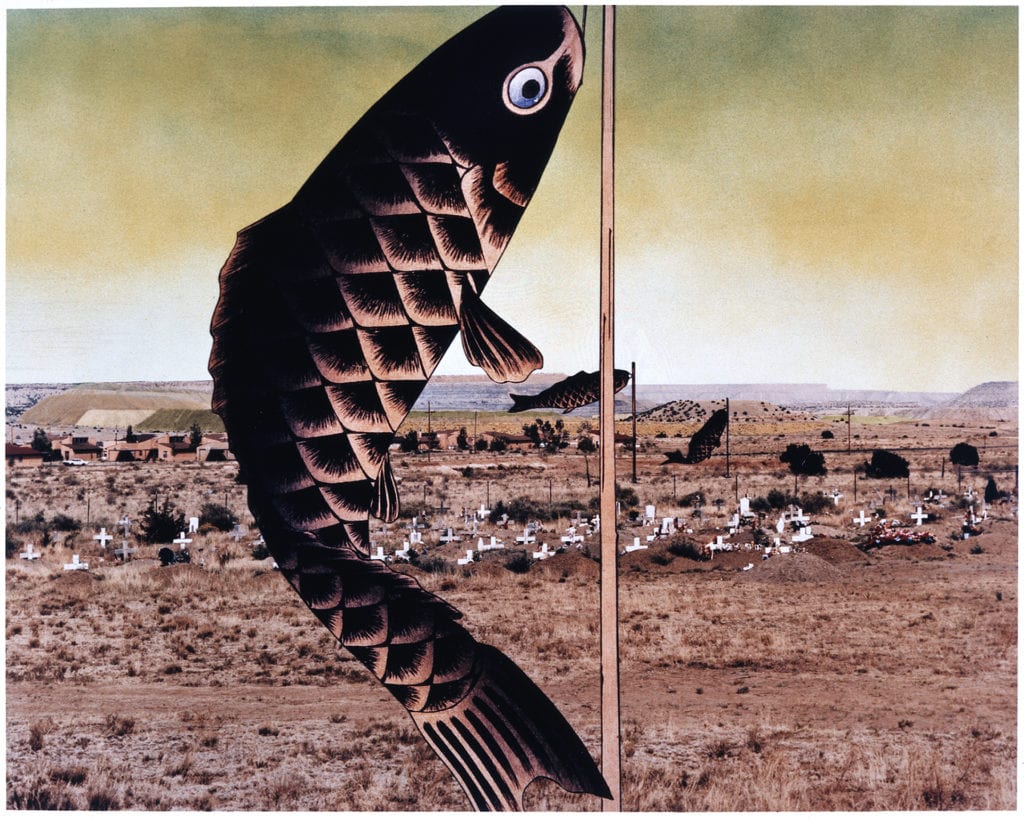

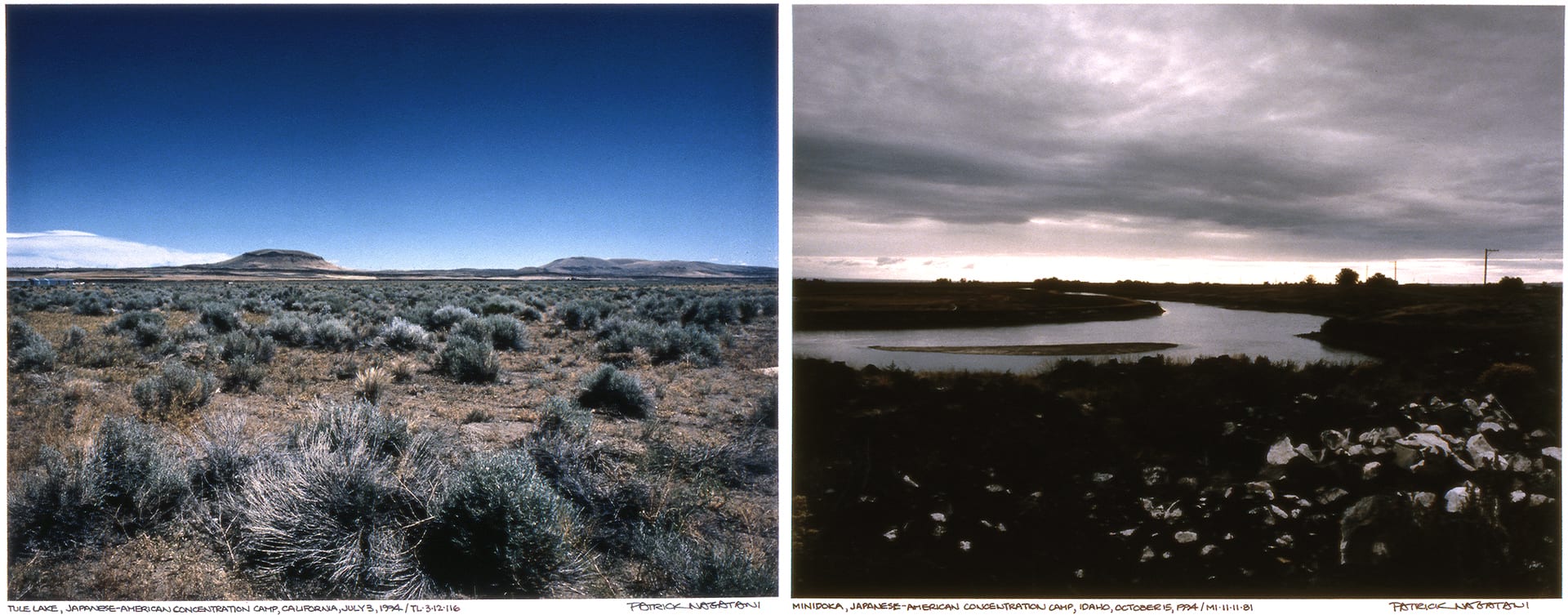

Understanding their hardships, Nagatani ventured to the individual Camps during the harshest conditions, his photograph captured the unforgiving frozen winter chill at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, and a scorching summer’s unrelenting heat in Camp Poston, Arizona. For Nagatani, the landscaped location of all ten concentration camps were spiritually connected to his ancestors, parents and ultimately, self-identity. The underlying depictions of these photographs are locations where one hundred and ten thousand Japanese Americans buried and planted their hopes, dreams, confusion and misconstrued shame. A reoccurring theme of the camp photographs illustrate glimpses of isolation and abandonment of life. Artistically, when all the camp photos are placed side by side, their horizons symmetrically “line up.” This is Nagatani’s attempt to demonstrate that while the uninhabitable terrain and weather conditions in each camp and photograph may differ, in essence, they are all one and the same and fall under the same sky.

Nagatani’s Concentration Camp photographic series is important and relevant in today’s political climate and agenda where immigrant children are inhumanely incarcerated , and traumatically separated from their families in prisons, disguised as detention centers. He unconditionally believed that mass hysteria based on gender, and/or racial classification circumventing Due Process requirements should never be repeated. His artistic camp photographs resound the message, “Never again means NOW!”

The origins of Nagatani’s Nuclear Enchantment photographic series is twofold. In the early 1900s, both paternal grandparents migrated to America from a small village on the outskirts of Hiroshima. Although they never returned to Japan, their families still lived in this countryside area. On August 6, 1943, Enola Gay unleashed an atomic bomb on Hiroshima City, the devastating blast killed over one hundred thousand men, women and children. Its giant radiation mushroom cloud, inflicted radiation exposure to future generations resulting in disfigurement and mutation.

In 1987, Nagatani accepted a teaching position at the University of New Mexico. He later discovered that on July 16, 1945 the atomic bomb was tested one hundred and twenty miles south of his new hometown, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Combined with the present-day uranium excavation sites, all located on Indian reservations, the Native American population is exposed daily to cancer inducing radiation.

Nagatani was a member of Atomic Photographers Guild (APG). The APG is an international collective dedicated to making visible all facets of the nuclear age. It emphasizes nuclear weapon mass production, nuclear power, reactor accidents, radioactive waste containment, irradiated landscapes, and radiated affected populations. Some of Nagatani’s Nuclear Enchantment works were displayed at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the 1990s and early 2000s. In October of 2015 an exhibition of Patrick’s work was displayed at the historic Hiroshima Bank Building in downtown Hiroshima. This building was one of the few that survived the atomic blast, being made of concrete and having a sturdy basement.

Being born a few weeks after the atomic bomb, having roots from Higashi-Hiroshima, and creating critically acclaimed art on nuclear issues, made Nagatani an important artist/activist who is recognized by the anti-nuke movement in Hiroshima. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, coupled with the current crisis in Fukushima, places Japan at the center of nuclear debates.

Many thanks to Patrick’s brother, Nick, for the thoughtful essay and to Lynn Estomin for the images. To learn more about Patrick’s work, Lynn’s film Living in the Story documents thirty-five years of his art-making and personal history.

About the artist

Patrick Nagatani was a teacher who utilized photographic art as his medium. For thirty-five years he taught photographic art, starting as a high school teacher in inner city Los Angeles, then as a Professor at the University of New Mexico. His teaching mantra never deviated, it was to find “passion” and “magic” in one’s work. His personal and profession forte was his immaculate focus and attention to detail, often bordering on obsessive. His passion was in the “journey” rather than reaching the “Inn.” While his photographs reflect an “image,” a mere moment in time when a picture is taken, the “process” in setting up the image was his passion and his reality.