Monstanto: A Photographic Investigation, devised by Mathieu Asselin, characterizes a shift towards conceptual documentary photographic practices that have expanded into terrain beyond the conventional documentary tropes of eye-witness testimony and photo-realism. Asselin’s approach is long-term, research based and adopts a number of visual and communication strategies that build the project as a multi-layered archive that can be adapted to various contexts and sites of presentation. Its depth and adoption of informational formats has the ability to communicate to wide audiences well beyond the art crowd of galleries and private views. It is a fight against a corporate, multinational giant, drawing attention to some very serious issues around agriculture, chemicals and food production on a massive scale. What it exposes affects millions worldwide and so being educated on Monsanto’s hidden world is pretty vital.

Photographers such as Asselin, passionately embroiled in their projects, can be thought of as social activists of a kind. They undertake what is an extension of photojournalism, borrowing its impulse and ethics, but is independent of news media or alignment with any public or private institution and so all decisions made about the project maintain authorial integrity. In this interview with Mathieu, we are joined by Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, an academic and a curator who has worked closely with Mathieu from the Monsanto project’s first public exposition. After a number of years of success and being widely acclaimed, it is a good opportunity to reflect on this work and discuss how it relates to social activism.

Sunil Shah: We last spoke in interview format at the Photographers Gallery and on American Suburb X in London during the Deutsche Borse Prize in 2018. From what I can tell, your project, Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation has not lost any momentum. Would you care to elaborate on developments as you see them?

Mathieu Asselin: The Monsanto project is a ‘Photographic investigation on Monsanto, a German multinational (acquired by Bayer in June 2018) specialized on agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology. By following the long and dark history of this corporation, I retraced the key moments that have shaped what Monsanto is today (contaminated sites, health issues on the population, economical and legal warfare, and so on) and to have a glimpse of what the future that Monsanto is shaping may look like.’ (Ref. Photo Monsanto)

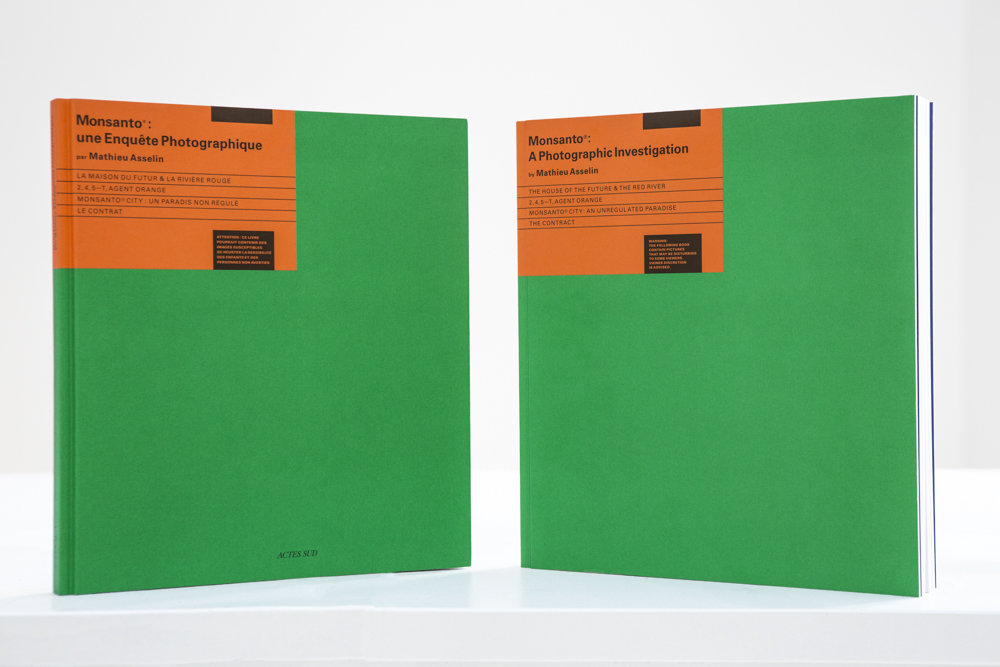

It all started with the idea of making a book and a 5-year photographic investigation that took me across the USA (2011-2015) and parts of Vietnam (2016). The Monsanto project is a book before anything, a book designed by the Venezuelan, Ricardo Baez. It was awarded several prizes and nominations and by 2017, I was invited to exhibit in Les Rencontres d’ Arles, a photographic festival in the south of France that has become its showcase point of reference for the photographic world. This marks the beginning of a new chapter for the project, a very important one—exhibitions. In 2017, I met the curator Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, who has become a key figure not only in exhibiting the project, but in helping me shape it into what it is today. Since then, the project has had twenty-five exhibitions in various forms and sizes (at museums, European Parliament, public and private galleries and schools), always adapting and responding to the social, economic or political contexts linked to the work (news, sponsors, locations, etc.). Each exhibition proposal, talk or workshop is catered to reinforce and preserve the consistency of the project and at the same time, the needs of the places or institutions that will exhibit it. It is a project that is very much alive, and this keeps me and Sergio on our toes, it’s a great feeling. Our next stop is at the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg later this year.

Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo: Yes, it has been quite a ride! Beyond meeting incredible people, we have learned to work as a team, together with Mathieu and Ricardo, and we have achieved a good critical dynamic. That is why we continue working on new projects together. Personally, as the curator of the show, I have taken on the organic character of the project very seriously. It is not simply a question of traveling with an exhibition and showing it again and again. It is about restructuring the subject and its concerns depending on the relationship each site has to its own environmental issues. This is the second challenge that the exhibition has presented us with—how to continue investigating creatively while we also showing the work—which is probably not common for a curator. I always say that my preferred definition of curating is as someone who takes care of something. This means taking care of every single aspect of this organic exhibition, from deciding the type of paper, the type and size of the frames, to the typography of the posters, the press release, to even asking myself who the sponsors are, every element in the presentation was made to count; the invitation card in the Amsterdam show, for example, did two things: serving as an announcement and as newsprint. Every detail presents a world of potential problems.

Mathieu: The fact that my research is related to a current issue has made us face important changes along the way, such as the moment we learned of Bayer’s interest in buying Monsanto. At that time, we were preparing the exhibition for the Deutsche Borse Prize, so we decided to write a new chapter in response. Not only was the space too small to tell the whole story, but we were facing a sponsor, the Deutsche Borse, who by selling Monsanto and Bayer shares, was an active part of my denunciation. It was an act of balance: on one hand, we have the sponsor of the prize actively profiting from the system we are denunciating through the commercialization of shares of Monsanto and Bayer. On the other hand, the privilege of being nominated by our peers in the photography world for such an important recognition. Nonetheless, it was also an opportunity we could not pass up. This opened new ways of showing the work, adapting it to current needs. This also triggered the creation of a new chapter we called The Stock Market and some new pieces: a newsprint containing the same information as the book—which we thought was a small luxury, new archival material concerning the circulation of my images in the actual press, and to me the most important piece—thanks to the free tablet application of the Deutsche Borse—two screens showing the price variations of Monsanto and Bayer shares in real time. Another important point I remember is the official announcement day of Monsanto’s purchase by Bayer in 2019. At that time, while traveling to an exhibition in Germany discussing how to react, we even thought of changing the name of the project for a second, which was impossible by the way. So, we designed and sent out a sticker of the Bayer logo, which we stuck on each of the newspapers for the show.

Sunil: I would like to turn to aspects of the project that reach beyond the context of art—photography festivals, awards related exhibitions, public and private art galleries and photobook related outcomes. For me, social activism is about breaking through to the public sphere and gaining purchase outside of the enclosed, privileged, intellectual, elite and institutional spaces. So, can you tell me to what extent this project transcends these private and protected spaces?

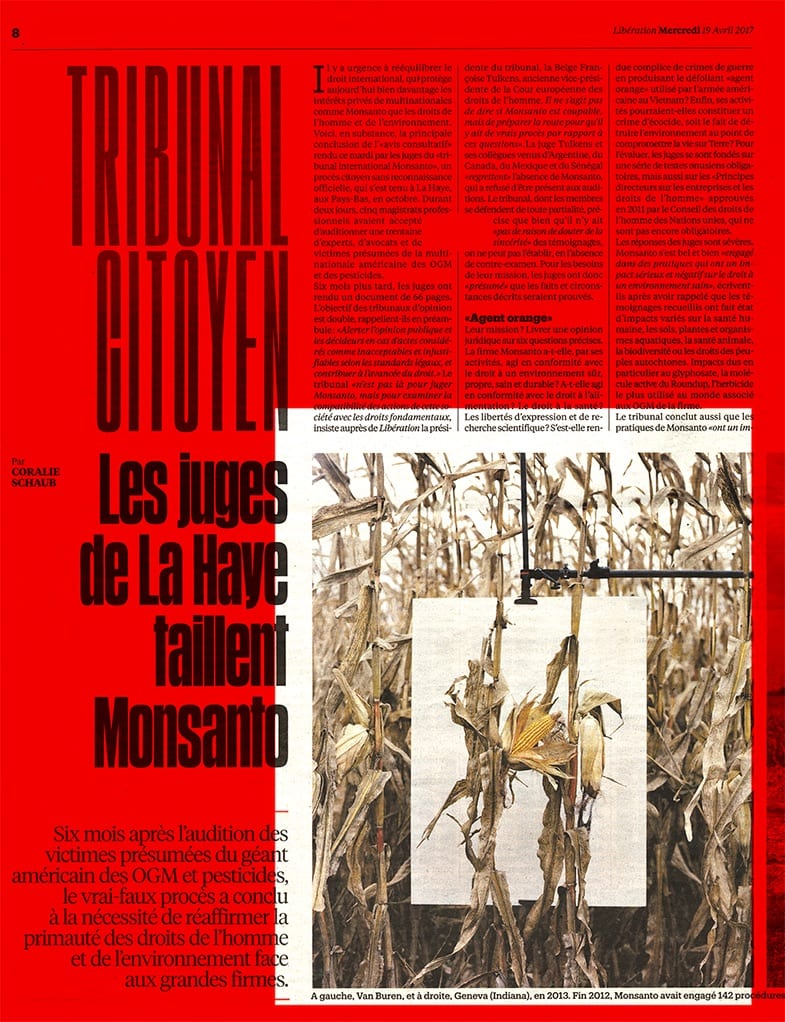

Sergio: There was one fundamental aspect that I understood, and that was that Mathieu’s work did not remain locked up in the field of art, although it was made visible through art. The project made a hole in the white cube and escaped. At that moment, the press “appropriated” it and the images began to actively fight against the use of certain phytosanitary products in agriculture in the context of the broad discussion about herbicides that was going on in parliament. Pictures were published in different media, the papers, the sizes where not the same, plus the words that now accompanied the images were: Glyphosate : How Monsanto is Wagging its Media War (Le Monde, 31 Janvier 2019), Hague Judges Carve Out Monsanto (Libération, 17 Avril 2017), Glyphosate, The Poison is in the Soil : Revelations on a Health Scandal (L’Obs, 5 Oct 2017). It was precisely in our programmatic decisions for the exhibition of Chapter 5: The Stock Market that we wanted to highlight the fact that we did not show the original photographs, but the chosen archival material, through a “gesture of quotation” (Ronald Kay), which were subject to various operations before being presented. The operations that we use belong quintessentially to photography in the mass media age: re-photography, enlargement, cropping, publication etc.

Sunil: I know last year at The Ravestijn Gallery, there was a public program attached to the Monsanto exhibition. Can you say a little about what that was, and which audiences were being reached through the program?

Mathieu: The exhibition at Ravestijn Gallery last year was the first exhibition of the project in a private commercial gallery, outside the context of a photography festival. Sergio and I came out with a proposal to Narda van ‘t Veer and Jasper Bode (the gallery directors) that transformed the gallery from a commercial space to an educational one for the period of the exhibition. The main focus was to open the discussion about Monsanto to a wider audience. For this, the gallery hired Macha Roesink as an educational content producer in charge of creating an “education program” and forging links between the space and the public.

Together, with support from the gallery, we are working on an alternative way to commercialize the project and to preserve its integrity: no individual prints for sale, only a full standalone series to avoid decontextualizing the work, as well making sure the series will be “publicly available” by avoiding the sale to private collectors where the work might be locked away, and instead focusing on non-profit institutions. For this, we are producing a Box designed by Ricardo Baez combining photographs, advertisements, documents, a first edition copy of the book, memorabilia, a curatorial text and digital access to the entire project. On a personal level, maybe this is not the smartest or simplest way of doing business, but I think these types of strategies are more sustainable and ethically viable in the long run.

Sunil: Has the Monsanto project been made visible to schools or colleges for educative purposes?

Mathieu: Yes, but not enough. I had a proposal to show in schools, public libraries and public institutions, some have worked, some not. Sergio and I have put in place a variety of exhibitions that can fit any budget or sometimes even, no budget. At the same time the work is publicly available, online or by contacting me. It has been already used by many institutions to teach photography and to talk about the climate urgency, agriculture, contamination, amongst other issues. The European Parliament, the School of Social Studies in Paris, schools, universities, public libraries, even a food festival, are some of the places where the project has been used for educational purposes. So yes, I think the work has been visible outside the photography world and we make sure that the mechanisms needed to pop the bubble are in place. But I understand that it is possible to do more; it is a learning curve.

Sunil: How much weight of responsibility do you carry with such a project? There is always a need to keep up to date with developments and as far as I can tell, it looks likely that this project could become a life’s work? In this respect do you think there might be strategies to move what you have started into a collaborative initiative that could become a foundation or a community?

Sergio: From my point of view, the responsibility we have today has to do first, with a global discussion and that is the problem of political art and its real political effectiveness: from the poems of Tzara to the works of Alfredo Jaar, including the reports of Larry Burrows. It is by no means a question of seeking to shine under the pretext of the injustice of the world, but to understand how to raise the pressure of what we believe needs to be said. In Mathieu’s words: “It is not the voice of an activist, but the result of the voice of a concerned citizen”. Monsanto is a seed that we continue to water.

In the meantime, our responsibility is to share our experience. Personally, I follow Luis Camnitzer’s statement: “art can also be understood as an educational process”. In 2019, we opened Double Dummy Studio (www.doubledummystudio.com) in Arles, a platform that creates a space for producing and showcasing critical reflections on documentary photography. The idea is to accompany the process of gestation and development of photographic projects centered around contemporary social-political problems in the form of talks and workshops. This is based on a relationship with the authors on constant dialogue and exchange. Which naturally brings together a community of photographers, critics, journalists and intellectuals to discuss and exchange information, ideas and experiences that highlight the current challenges, prospects and frontiers in contemporary documentary photography. Our next workshop The Camera as Political Apparatus II: An Unromantic Take on Documentary Practice will be held in June at the Annual Program in Noua Atelier in Bodø, Norway.

For more information on the last bilingual 2019 expanded edition of Monsanto: a photographic investigation, visit here.