“It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world, we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relationship between what we see and what we know is never settled.” (John Berger Ways of Seeing, 1972; page 7)

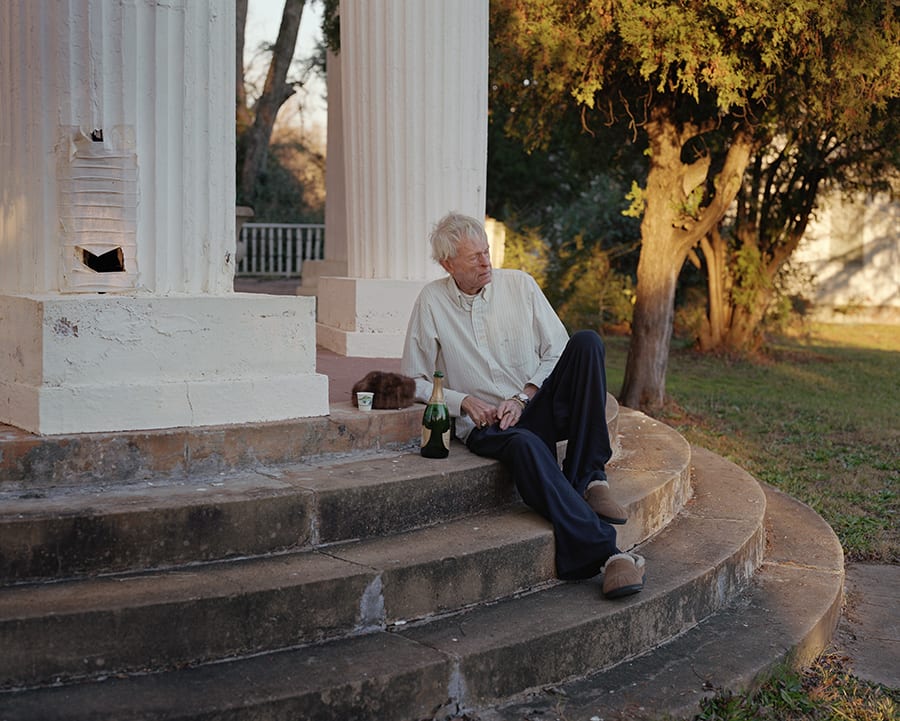

Morgan Ashcom’s sprawling project What the Living Carry intentionally muddles and confuses the conceit that photographs help us to see and perhaps better understand our world. Instead, these images play with the narrative potential of the medium. Oscillating from landscapes with lush foliage to run-down buildings and streets, these pictures call to mind all too familiar news stories on broadcast television. In their vague familiarity, these photographs illustrate the ongoing desire for photographs to tell stories. They give the impression of a singular place that has been impacted by an unidentified, yet widespread, hardship. A difficult past, along with a seemingly limited potential for the future, is evident on the faces of those who periodically appear. Specificity is essential in the creation of both meaning and myth. The crumbling structures, overgrown plant life, and what appear to be potential crime scenes, all point to a feeling that one is seeing a town stymied by economic depression. In such places, mythologies about the past often loom like a shadow and can be hard to escape. Successes and failures are tied to these spectral mythologies and are often passed from one generation to the next, embedding the weight of their trauma into our genetic codes.

This play with fiction and fact is a central theme. The sites depicted are not a single place, but include a wide geographic span along the East Coast, from upstate New York to Southern Georgia.1 The story becomes further complicated by the inclusion of letters addressed to a person named Morgan from a scientist, or perhaps a lab-technician, named Eugene. This mononymous man of science works at the enigmatic Center for Epigenetics and Wellness of the Spirit, a place with a name that vaguely recalls the New Age movement of the 1970s but is concerned with the study of the physiological expression of genetic mutations caused by trauma, a subsection in the field of neuroscience. Complete with a generic Yahoo email address, we learn a little about Eugene’s temperament and Morgan’s desire to have his DNA tested. It’s a one-sided correspondence as Morgan never responds. The letters are both amusing and frustrating as their relationship with the photographs in the project is never fully articulated.

The tangled mass of trees that populate much of the terrain reveal the romantic potential of a place that also bears the weight of the violence that defines large aspects of this country’s past. The literary legacy of William Faulkner is reflected in the tone of these images and perhaps rivalled only by the heroic landscapes associated with the Hudson River School. These versions of the American landscape can coexist in this place not only because these images serve as a stage for a story, but also because every place is ultimately an amalgam of different people’s ideas. Despite working towards a composite narrative, Ashcom’s photographs trace the reality of the sites photographed. One only needs to look at the photograph of the bright red house with shutters, wooden columns, and an empty brick flowerbed painted an electric blue. The windows on ground floor reveal the reflection of the photographer and his tripod.

The photography historian Liz Wells has written eloquently about the way visual culture can function as empirical proof and characterize the photograph, specifically, as witness that offers descriptive testimony. She argues that this approach to photography “ultimately rests upon the view of reality as external to the human individual and objectively appraisable. If reality is somehow there, present, external, and available for objective recording, then the extent to which the photograph offers accurate reference, and the significance of the desire to take photographs or to look at images of particular places or events, becomes pertinent.” 2 While Ashcom’s photographs offer traces of individual sites that exist in the real world, one needs to move beyond this reading and consider the litany of visual references that inform his approach to making pictures. These photographs operate at the intersection between fact and fiction and are driven by a narrative that is never made explicitly clear and instead invites the viewer to consider multiple possibilities.

Despite the factual existence of these sites, the photographs that comprise What the Living Carry remain enigmatic. Views of verdant foliage, densely crowded webbings of thin leafless branches, old growth forests, and a river meandering into the distance as the evening sun casts a warm glow over barren trees—all of these pictures help to establish atmosphere. The landscapes are somewhat homogenous in their appearance, despite the broad geography traversed by the photographer. Some of the images function predominantly as devices to establish tone while others as sets for a scenario that has yet to unfold. Along with the broad views that give a sense of scale, there are an equal number of pictures where individual details like the surface texture of a column or the attire of a person are of paramount importance. While the influence of modern cinema plays a role in understanding these pictures, they are more closely aligned with a view of the world as articulated by photographers as disparate in approach Walker Evans and Lewis Baltz.

As is the case for most artists with a formal education, Ashcom’s photographs are laden with allusions to the work of those who have come to define the broader history of the medium. The divide between architecture and nature is a recurring motif in this project and can suggest the influence of many different twentieth century photographers. The documentation of the vernacular and the interest in the aesthetics of functional objects closely align these pictures with the work of Evans. Clément Chéroux, the curator of the 2017 exhibition Walker Evans, notes in his essay The Art of the Oxymoron: The Vernacular Style of Walker Evans, that the notion of the vernacular played a significant role in creating a national self-identity. While “in Europe the vernacular had largely contributed to the formation of regional cultures, in the United States it participated fully in the development of a national identity.”3 Evans’ presentation of the vernacular was part of an expression of a distinctive national style that was defined in opposition to high culture and therefore considered democratic. The dissemination of his photographs in magazines like Fortune, further underscored the accessible nature of these self-consciously artistic images of quotidian subjects.

A lifetime separates the works of these two photographers, yet the geography traversed by each is largely similar. In looking at Ashcom’s photographs, a viewer becomes aware that his subjects bear the physical evidence of the passage of time. Pictures that emphasize the accretion of paint on a surface or cracked windows desperately in need of repair are testaments of such changes. Two black-and-white pictures that feature signage located in nature are especially pertinent, despite the vastly different spirit of each. One, an official signpost that directs people towards the Department of Corrections, is set amidst a landscape thick with lush foliage and powerlines receding into the distance. The painted arrow points the way to a state prison and the thick overgrowth of nature reinforces the idea of confinement. Yet this photograph also embodies the dichotomy of freedom associated with nature and the notion of enclosure as literally spelled out by the sign. The other photograph depicts two hand painted signs located in the middle of a chaotic composition. Hanging one on top of the other, they read “Hypocrite” and “Sex Pit Help Me S U,” and peek out from behind the branches of a coniferous tree. To the left, a barbed wire fence is barely visible and functions as an ineffective barrier between the two rusted steel containers and a foreground littered with felled powerlines. While both photographs suggest the presence of people, the visual clutter in the foreground of the latter also indicates the remnants of physical force. Both of these pictures point to the importance of the role of the vernacular in understanding how communities define themselves.

In thinking about these photographs representing actual locations without conforming to established definitions of the documentary tradition, it is also worth considering the work of Lewis Baltz. His 1984 project San Quentin Point walks a line between aestheticizing vignettes drawn from the landscape and depicting a completely dystopic view of human activity. To create these photographs, the photographer tilted his camera towards to ground and largely filled each frame with foliage and discarded trash. While the title reveals the location of where the pictures were made, this is a landscape that seems largely alien in nature. What the Living Carry is punctuated by similar photographs depicting dense foliage and traces of human presence, but most are rendered in color and largely avoid the feeling of Baltz’ oppressive precursor.

In a nod to the general role of fiction functioning within Ashcom’s project, the photograph of a white metal clad storage facility, with four yellow safety poles awkwardly leaning in different directions, seems a familiar subject. The depiction of this vaguely industrial landscape takes as its primary subject matter the bland and cheaply constructed industrial park that became popular during the 1960s and 1970s and which crept into urban and suburban spaces around the country. It became a favorite subject of Baltz during the early part of his career. This particular photograph by Ashcom seems to fuse two very different pictorial traditions that Baltz explored throughout his life. In subject matter, it channels Baltz’s photographs of the suburbs of Irvine, California yet in approach it is deeply invested of the cityscapes he made after moving to Europe nearly two decades later. This one picture collapses two separate approaches to picture-making by the same photographer.

Taken altogether, Ashcom’s photographs demonstrate a reflexive knowledge of the history of photography and provide carefully articulated references that position him in dialogue with celebrated practitioners of the twentieth century. These pictures are not traditional visual documents that aim to persuade through accuracy and objectivity. In her 1977 essay In Plato’s Cave, Susan Sontag suggests that photography has become the primary device for experiencing something and also giving the appearance of participation, but that the medium is “essentially an act of non-intervention.”4 Ashcom works on the periphery of this way of understanding the world. There is clearly an interest in blurring the lines between mediation and maintaining the façade of the objective viewer. He slips between these two worlds and prioritizes the potential of being confronted with something that looks familiar yet remains enigmatic. Using visual cues that can suggest stories associated with certain geographies, What the Living Carry celebrates atmosphere and mood over decisive narratives.