Tarrah Krajnak was born during a tumultuous period of military rule in Peru, adopted by Americans, and raised in the Midwest. She uses images, found and original, to navigate this personal history and experience. Krajnak‘s work offers insights on the nature and history of photography, international politics, and familial relationships. Her photography-based practice has grown to incorporate video, performance, and now with El Jardín De Senderos Que Se Bifurcan (2018), artist books.

Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett (EGJ): Let’s first start with the very basics. What is this book project and how did it come about?

Tarrah Krajnak (TK): El Jardín De Senderos Que Se Bifurcan is an extension of work I started several years ago in Peru called SISMOS79. I’ve been exhibiting this work now for the last three years and in that project, I was interested in understanding my relationship to larger social and political histories of Lima and the circumstances of my birth and adoption. The book project became a way for me to think through many of the same ideas, but with some distance and through the use of meditative poems and experimental text. The task of the book is different from SISMOS79 in that the book looks at the “process” of tracing origins; it attempts to make evident the nature of trying to figure out where one comes from.

EGJ: And so, the images in this book took place over what period of time?

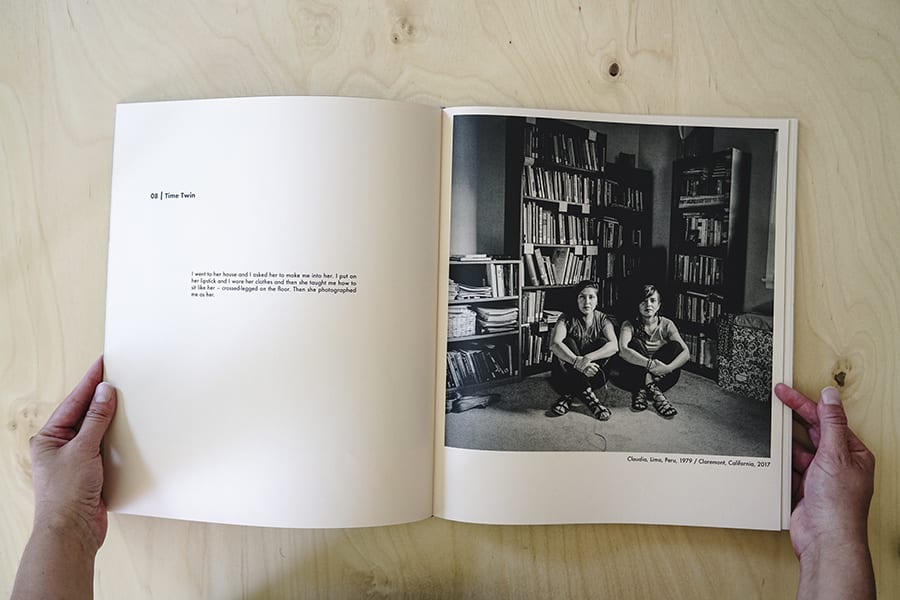

TK: The images in the book were all made over a period of several years, and some were taken from earlier points in my life from unfinished projects. The writing occurred much later as I started to reflect upon the materials I used in SISMOS79. I collected over two hundred 1979 Peruvian political magazines over a couple different trips to Lima. Many of the archival images you see that have that dot pattern were Xeroxed from that collection of magazines. I made an earlier project in color with those magazines that were more about sculptural forms and color. I wanted to use the magazines in a different way here. I started marking incidents of violence against women in the magazines and then used those photographs in the book. The collection of passport photographs you see were found and collected over a three-year period and then the portraits of women born the same year as me that I call Time Twins were taken in 2014 and 2017. The images at the beginning of the book were taken at completely different points in my life. One of the themes in El Jardín is this idea of twinning or doubling. I went back through my archive and curated images that seemed to fit. The images emerged. I realized that a lot of photographs I naturally take are so well balanced and have this formal aspect that relate to the double or twin or halving. I also think that the book has a lot to do with photography itself and my relationship to the medium, so there is a lot of repetition and re-photographing.

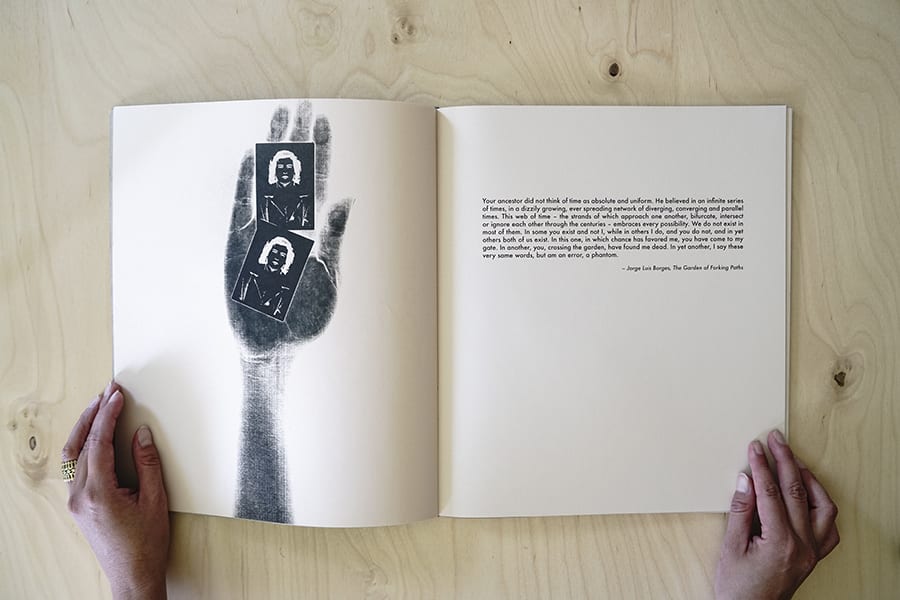

EGJ: Moving through the book, I get a sense of time being conflated—portraits from the 1950s and 1970s, periodical reproductions, your own original photographs. Combined, they convey a sense of moving back and forth. It makes me think of magical realism in Latin American writing, especially as you begin with a Jorge Luis Borges quote from The Garden of Forking Paths. Can you walk me through how this element of metaphorical or abstract narrative became a part of your photographic process?

TK: I started with the Borges story because I loved this idea of simultaneous or parallel existence. It relates to the experience of the transracial, transnational adoptee. In the early days of international adoption, total assimilation was the unquestioned goal for many parents, mine included. Children like me passed between families, races, and histories. An identity that emerges out of this experience is one of instability–one that could never be seamless. When I went back to Lima for the first time since I was an infant, I was almost thirty years old. I felt outside my body, but as if my body belonged there. I did feel this intense sense of parallel existence and of loss or mourning at this bodily exile. I look like the people there, but they talked to me in Spanish and I could not respond. I felt shame. This experience of instability is what motivated me to find other women born the same year as me in Lima to find my Time Twins. I found them through ads, then I photographed them and recorded their stories and personal histories. I put this work aside, and then several years later, I listened to these stories again and again, memorizing their words. I began to repeat their stories in my own voice out loud to Google translate. This led to mistranslations, which became a way of experimental writing. I created a parallel story with the text that is both my lived experience and theirs through mistranslation, mis-remembering, and mis-pronunciation.

Time moves in all different directions in the book and the photograph itself is also deceptively “still”. The images you see from the 1979 political magazines are re-photographed and Xeroxed, then re-photographed again. In one of the images, I placed dried roses on top of the Xerox and copied them again. So, my relationship to the archive is one of resurrection—trying to re-claim this history through repetitive acts of copying.

Here, I am thinking about the photographic process itself as a way into abstract narrative. The act of photographing for me and the way the image exists in different times–the time it was taken, the time I found it, the time I studied it and re-photographed it, and then the time of viewing it in the book. Does that make any sense?

EGJ: Yes, that is what I was trying to get at, but now I want to pull out two things that you touched on in this answer. First, the materiality of the book. You use a Xerox, which places this book in line with self-produced zines, but your book is a little more sophisticated than the usual DIY aesthetic. There is an intention in the way you crafted the book that is evident in the different textures. It starts with soft cardboard binding, and the black images are printed on a smooth, rosy, manila paper. Some images have the heavy texture of a Xerox copy and others are crisp, taken directly from your image. How did you make these choices?

TK: The materiality of photography has always been an important part of my practice. I take pleasure in photographs as objects and in handling and holding them. Books give you a similar living, breathing experience in the turning of a page—the way different books feel in your hands, the way they can sit on a shelf, spine out. The size of my book is fairly large at 22 x 25 inches when opened, so the action of turning a page is more tangible and less precious. The book itself feels soft and smooth in your hands. I like the humble qualities of the materials as well: chipboard cover, Xerox, the softness and warmth of the paper on skin. The scale of my own hands are reproduced on a one-to-one scale, as if I am reaching back through time. The choices I made in relation to image quality allow the viewer to understand the movement between time and space as you mentioned earlier. I use the lo-fi quality of the Xerox or pinhole (twin bed photo) to create distance, while other images like the Time Twins were taken with a really sharp Hasselblad lens so they appear closer and more recent.

EGJ: This brings me to the second point: a sense of traversing is also echoed in the language of the book. You have text in English and Spanish, the latter being your birth language and the former your native. At this time especially in our country, it seems the like the words we choose are especially loaded, potent ways of identifying ourselves and our allegiances. How much of the text do you expect readers to understand or learn?

TK: The way I use Spanish in El Jardín is connected to the understanding of language as a home or, as philosopher Martin Heidegger calls it, a “house of being.” In this book, Spanish is a home I can’t enter, and yet, it’s the language of my ancestors. So much of the text in this book is meant to carry meaning in a different way then and to be read as one might read a photograph of a re-photographed, Xeroxed magazine page. For example, the text in the Time Twins section is made from so much movement between Spanish and English and so much mistranslation and faulty memory that what remains is a ghost text; it’s not entirely there. Then, paired with the close-up portrait of Rosa whose mouth is slightly open, one can see her speaking, but there is no “real” access. I wanted the poems to function at this level. The poems need the photographs and the photographs need the poems.

The questions of identity are so much more intensified right now, but for anyone who straddles multiple identities—people of color, biracial people, mixed race families, immigrants—we have grappled with these issues our whole lives. Who are my people and where do I belong? At the heart of the “American” experience are these essential questions and the myths of unity and cohesion that underlie the notions of national identity, origins, original past, birth place, birth mothers, native. These are ideas I have explored as an artist now for over a decade. There is something profoundly unsettling about trying to trace one’s origins and then finding orphanhood at the beginning of things, finding absence. I find comfort in writers like Borges or Ana Mendieta who confront this condition. “There is no original past to redeem,” Mendieta writes.

EGJ: And those issues seem to have always been a part of your work going back to the Kloes series. This reconciling of yourself with your surroundings is especially present in your photography and performances of the Ansel Adams body of work, but that series seems more intellectual than personal to me. I think of your academic side attempting to change the narrative of modern photography, or at least integrate it. It is interesting to me that the project stems from a book by Adams. Let’s talk more about your interest in the history of photography and engagement with it. What brought you to this medium? And how did you decide to integrate performative elements?

TK: Yes, sometimes I think it is difficult to see the conceptual threads that tie my work together because I use so many different approaches and the resulting aesthetics vary so much. My book project, my recent Kloes series, and the Ansel project are all concerned with return or tracing my origins and questions of belonging or positionality. These questions are equally intellectual and personal in each of the series. I often think about the histories handed down to me and how I am shaped by these inherited narratives–whether it is my own family history or the history of photography itself. In the Kloes project, I documented the ruins of a century-old garment factory in eastern Pennsylvania where my grandfather worked for nearly 50 years until his sudden death in 1997. I returned 20 years later to discover the decrepit building still standing and full of his personal belongings as if he never left. The project is ongoing, as I am unraveling a deeper history of labor exploitation and the ways that the mining industry left palpable psychological and ecological wounds. In tracing my own lineage as a photographer and thinking about how we teach the history of photography to younger generations, I started to re-visit “fathers” of modern photography– figures like Ansel Adams and Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson. I titled this work Master Rituals, and I began by trying to embody these photographers. I wanted to “be them” and this initial desire turned into performative gestures. I started shooting street photography with a Leica, learning how to shoot 8 x 10 and 4 x 5 large format photographs at an aperture of f/64. I studied diaries and notes and watched films documenting how my “masters” worked. In the case of Adams, I became really obsessed with his book The Making of 40 Photographs. In it, he looks back at his long career and picks his top 40 photographic “hits,” so to speak, and describes how he made them. It’s actually really boring technical information and the writing itself is tedious, but hidden within his text I found beautiful, poetic language. I started to create my own poems through redaction of Ansel’s text. I placed my own top forty hits over Ansel’s. I then took this gesture further and further and performed it several ways: with my hands, with my hair, with my body. What emerges out of these performances straddles homage and erasure. I’m still working on this series now.