In the Spring of 2019, Derrick Woods-Morrow, self-coined activist-deviant-scholar, and artist, brought together a group of friends to collaborate with him on an experimental performance titled Box 64: Acts of Boyhood Divination. The guidelines for some of the interactions that would take place at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago were printed on a floating sheet of fiber-paper. They read: ‘‘Find someone of color / Tell them they can build their own future / Give them a box of 64 / tell them there is no center / There is no end (…) be hopeful they are queer.’’ To me, it read like a divinatory map. I pondered a long while on this offering. It, of course, made clear some of what Woods-Morrow’s work questions: issues of race, gender, identity, memory, but it also proposed an alternative. While a lot of the contemporary discourse around Queerx and contemporary Black practices refers to futuristic possibilities, I am drawn to practices that offer immediate, transformative, and generous gestures. What speaks to me about Derrick Woods-Morrow’s photographs, installations and videos are their anchorage in reality and their soothing impact. In many ways, instead of catapulting us into what’s possible, the artist makes the alternative future we yearn for already present. Whether it be by handing a kid a set of Crayolas in Box of 64, by creating a memorial to gay cruising in Washington Park, Chicago, which he did in the summer of 2019, or by reaching out to me when we were both feeling down, the moves we need to make, he has already made.

When I first encountered Derrick, we started an animated conversation around stillness. At the time, several of his installations were exhibited at Aspect/Ratio in Chicago, and he had developed a large body of works appropriating tapestry techniques resembling French toile de jouy. Instead of its usual pastoral illustrations, the linen fabric he reprinted featured characters extracted from Jim Crow era archival photographs that depicted Black folx in moments of leisure. In the gallery, the central space was occupied by a sculptural boxing ring made of wood indigenous to the artist’s native North Carolina; sand excavated from Rainbow Beach, Chicago and Lincoln Beach, New Orleans; and plush adult sex toys – covered in upholstered fabric. Sitting in the middle of the room, the piece questioned both the violence inflicted on bodies, specifically those of Black, queer, trans, non-conforming, disabled—the list goes on—people, and at the same time the softness, which they are not often allowed. We chatted about rest, and I remember mentioning to him an incredible series of drawings and paintings by Detroit-based artist Mario Moore, who chose to depict Black men at ease. Along the walls, a series of archival photographs, shot in black and white on a seashore, conversed with the depiction of Jim Crow era figures on the ring. The silhouettes on the beach were those friends, allies, non-binary and non-conforming folx, photographed along the Coastal South, where Derrick Woods-Morrow is from. By depicting them within these historical, scenic shores, the artist restituted some of what his and others’ ancestors were deprived of: a space to regroup and recharge.

The pastel tones, which colored his toile de jouy in blues and whites, seem equally perceptible in the artist’s most recent video, Much handled things are always soft, dated from 2019. Despite its energetic inaugural scene, the images slowly embrace and bathe the viewer in the dappled shade of Chicago’s elm tree leaves. As a result of Woods-Morrow’s encounter with longtime AIDS survivor Patric McCoy, Much handled things focuses on the effects of AIDS on the Black queer community. Conversations between friends, the artist, and McCoy constitute the film’s sonic backbone, while the images show a series of couples making out in the park. Two successive music segments from Whodini’s Friends and Freaks Come Out at Night together propose an entry point into the work. This musical introduction very aptly summarizes the core theme of this work: paying tribute to the many Black men lost to the global AIDS crisis and the history of public sex culture in Chicago, it could not have been better set in motion. Whodini’s lyrics still thump: ‘‘the freaks come out at night.’’

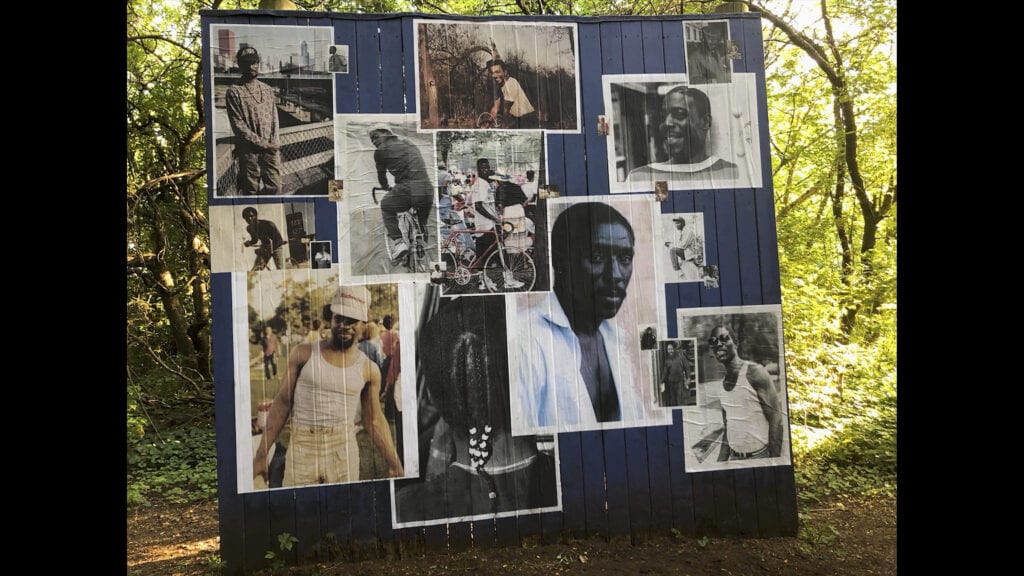

Sequences oscillate between intimate moments and documentation of a performance during which Woods-Morrow and his friends covered up with posters a wall that had been built to gate off a cruising ground in the park. The use of sound, however, disrupts this gentle pace. Rejecting a certain kind of respectable queerness—should it even be called queer?—Derrick Woods-Morrow’s works question concepts of rest and love, sidestepping logics of productivity and embracing joyful sexual practices, including those often dismissed as obscene. For the artist, the open exposure of kinks constitutes a practice in itself. I remember reading him say in an interview: ‘‘at the dinner table with my mom, when I go home, we talk about glory holes. It is very much like activism for me to be so vocally sexually charged.’’ The dissonant sonic moments in the video operate similarly, casting a shadow of doubt on the respectable and easy confidence displayed by the folx interviewed or filmed in Much handled things. Five minutes into it, we’re assailed by distorted, sour laughter, which disturbs a moisty kiss as if to remind us of the incessant vociferations of the oppressor, the homophobe, or the bully.

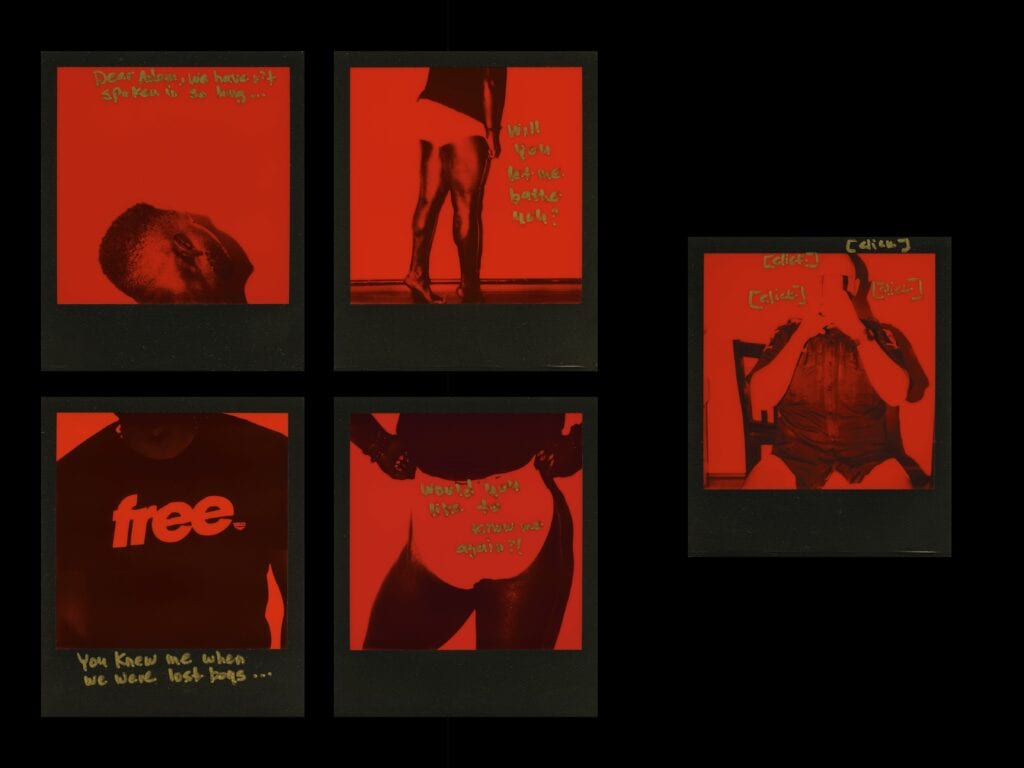

The artist’s use of the off-camera space is both consistent and incredibly masterful. In this video, he chose to insert black frames between saccadic sequences of lovemaking, creating blank spots in the viewer’s vision—moments of intimacy that hint at a space beyond sight. Similarly, his earlier film, The Roach is Coming (2018), revolves around a cleave between visual scenes displaying two twin white adolescents performing under the director’s vocal direction and off-camera moments. The artist discusses shared experiences with a childhood friend he’s bathing. Once a lover, Adam, the bather, has become a police officer. Concerns around the performativity of boyhood, manhood, and race, emerge in the interstice between the visual and off-camera scenes, initiating a co-performative process in which Derrick Woods-Morrow, making his directorial role present, participates both as a filmmaker and often subject of study.

This role is further developed in the series created along with the video, which includes a set of sixteen Polaroid pictures, annotated in red and blue, and large black and white photographs. Each of the Polaroids includes handwritten captions, each of the colors corresponding to one of the protagonists, Adam and Derrick’s conversation overflowing the space provided by the small 4 x 3 inch prints. The set of larger black and white photographs depict Adam more frontally, but the photographer remains as visible as his subject. Adam is often portrayed hiding from sight, his hand raised to mask his features, and we feel a certain ambivalence towards the camera, as well as Woods-Morrow’s inquisitive gaze. In one of the Polaroids, fully tainted with red, he sits on a chair, holding his cell phone in front of his face. Playing with the captions, Derrick Woods-Morrow forces our eyes to tilt back inwards. “Click,” “click,” “click,” reads the caption. This time, it’s not Adam’s body on the line; no fixed positionality here.

The notion of liberation is central to many of these works, Woods-Morrow’s exploring restricted or complex accesses to freedom, not restricted to, but including, Black sexual freedoms. For an ongoing body of works that began while he was at the Fire Island Artist Residency in 2016, he established contracts with predominantly white men, who, in order to have sex, gave him access to their image archives and sometimes their clothes. In this project, the digital realm and the lovers’ cell phones are both mined as source material for the work. Relinquishing their rights over their image, participants gain sexual freedom. But is that really what freedom means? Isn’t all sex transactional? The fluctuation between the give and take, and the objectification a body can be subjected to, are key to this and several works created by the artist during the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent example of this would be a conversation recorded with Oakland-based fag icon, writer, musician, dancer, and director Brontez Purnell, which turns into an intergenerational exploration into possibilities for pleasure and intimacy in a 2020 context. An online installation, the upcoming INTIMACIES, pushes the idea further. It aims to create an expansive archive of Black folx stories, engaging with Internet communities and digital sexual alternatives such as Jack’d or OnlyFans. Using the social media platform utilized by over five million BIPOC gay and bisexual men and OnlyFans, a subscription site that allows content creators to monetize their influence, the artist explores how new digital opportunities have provided a haven for Black folx, lovers, and sex workers alike.

Evocative of the ceramic sandcastle sculptures the artist used to build, this new digital project constitutes a safe space full of holes, cracks, kinks, and loops. Like the constructions made out of his childhood playground’s clay, INTIMACIES is porous and ever-changing. A process-oriented work, it will evolve over time, depending on the contributions, intimate connections, and interactions inherent to Woods-Morrow’s practice. Members of his chosen family—his queer-kin, as he calls them—have a central role to play in it. As such, INTIMACIES isn’t only a space of validation of Black queer folx. It creates a platform for mutually beneficial exchanges and new structures of the sexual economy. And while 2020 has been for many an incredibly scary year of isolation, fear, and depersonalization, the queer-kinship Derrick created for himself, and others, feels incredibly homey. In continuously co-creating this home as a space for multi-dialogic experimental encounters, the move he makes sounds more powerful than the many others I’ve seen, constructed over ideas of family, blood, or shared custody. For all these reasons, and while we justifiably worry about what the future will bring, I’d offer you the same guidance the artist offered me for the days that are here and the ones we foresee:

“Be hopeful they are queer.”

About the artist

Derrick Woods-Morrow’s (b.1990) work is a meditation on deviation and disruption of language and representation – the laborious and the playful. Originally from Greensboro, North Carolina, Woods-Morrow is currently based in Chicago where he works as a sexual health advocate and activist. His artistic practice explores black sexual freedoms, the complicated histories concerning access to land, and the navigation of the American terrain by black and queer peoples. Woods-Morrow received his MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2016 and was most recently an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Photography and teaching artist at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He has exhibited nationally and internationally, including in the 2019 Whitney Biennial in collaboration with Paul Mpagi Sepuya; at Kunsthal KAdE in This is America | ART USA Today (2020); at the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans in Make America What America Must Become (2020); at The Center for Photography at Woodstock in Photography Now: THE SEARCHERS (2019), curated by Maurice Berger and Marvin Heiferman; and at the Smart Museum Chicago in Down Time: On the Art of Retreat (2019.) In the winter of 2019, his second short film, Much handled things are always soft debuted in collaboration with the VISUAL AIDS 30th Annual Day With(out) ART programming at the Whitney Museum of American Art; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; the Brooklyn Museum; the New Museum; and over one hundred institutions worldwide. He is the 2021 Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation Fellow at The Center for Photography at Woodstock, a 2021 recipient of the Bemis Center Residency, and a 2021 AntennaFellow, with previous residencies at the Fire Island Artist Residency and Chicago Artists Coalition’s Bolt Residency. He is a recipient of the 2018 Artadia Award – Chicago.