“Papi, Papi, Papi” is an excerpted prologue from Oli Rodriguez’s artist book Papi recently published by Candor Arts. In Papi, Rodriguez revisits the eighties and nineties era of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The book incorporates photography, video performance, and dialogues between queer Latino communities and those ravaged by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Rodriguez’s project started as a performance where he sought out men who have had sex with his father. These encounters exist as video and email messages, which are then presented through photography. Rodriguez’s photography explores the remnants, the changes, the barrenness, and the historically lost subtext in the contemporary landscape. Though his photographs initially started by retracing his father’s experiences, the project has opened up a dialogue on the mass devastation of queer men during the HIV/AIDS pandemic. “Papi, Papi, Papi” was originally developed and published with support from the Poetry Foundation.

papi: father

papi: a term of endearment for a child, primo, masculine tía

papi: sexualized latinx gay / queer call, “hey papiiiiiii!”

Death opens up so much space.

________

1980s traversing lincoln park to Boystown /Lakeview to Humboldt Park, Chicago, IL.

Queers, drug users, families of color, and lots of puertorriqueñx.

And then it wasn’t.

My Papi, Peter, lived in Chicago neighborhoods, Humboldt Park,

Lincoln Park, and Boystown/Lakeview.

(Or Pedro or Troy, depending on what neighborhood he was in.)

A cruising sex worker who worked many neighborhoods under

many names.

I lived primarily southwest of Lincoln Park in a neighborhood that had no name.

Until gentrification started in the early 1990s and then it did.

West Town.

1980s gentrification had emptied Lincoln Park of Puerto Rican families,

pushed west and flooded into the Humboldt Park neighborhood.

The continuous push West then South,

then out.

________

1980s, Lincoln Park, Chicago, IL.

Frequented as a child with my Papi,

my ass pressed hard against the middle bar of his bike.

His arms holding me close

amidst the sex,

verde public cruising spaces

where the butterfly museum is now.

Called Knob Hill then.

Gentrification / colonialism changes the language we speak.

There is so much cum under the butterfly museum, my Ma says.

As one approached the hill the rise and fall of bodies was distinct.

Lake Michigan, water beating background.

Everyone was fucking everyone, my Ma says.

________

Belmont Harbor, Boystown / Lakeview, Chicago, IL.

Working class POC families enjoying the beach,

with blow jobs beneath them on the rocks of the harbor.

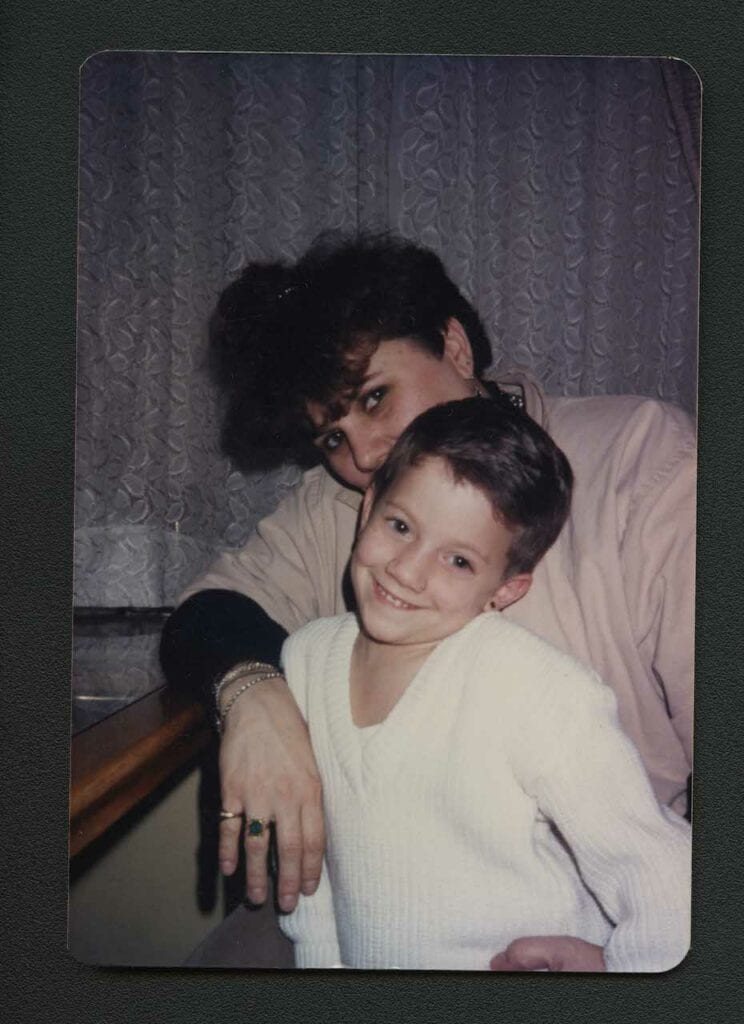

My Ma and Papi met a mile away in the basement of a private school,

Francis Parker, working as janitors.

I was conceived in an elevator, going up.

________

I grew up in a gay disco. It was a triad of queers, kids, and cats.

Dress-up was a mandatory event.

He had so many hats!

Construction worker, feather boa, baseball, ’80s mesh, fedora,

all the white black leather pleather.

The black leather cap—that was my favorite.

I learned the walk with that cap.

I strutted through his apartment,

while my other papis / father figures / queer padres and the

dragboygirlqueens

yelled their approval—

Heyyyyy papiiiiiii,

get it girlllll!

Work it.

It was a fashion show;

a practiced, polished, queer strut.

An owning swagger that my small self had mastered

while watching the drag queens and trans* folk perform in gay bars.

I had been kicked out of more gay bars than any other eight-year-old.

I was proudly his sondaughter—genderfluid and a super gay,

as my brother called me.

Beyond gay.

Queered.

I was a verb.

An action.

A past tense active verb porque I was always queer, other.

I am an epidemic child, not birthed but raised by AIDS.

________

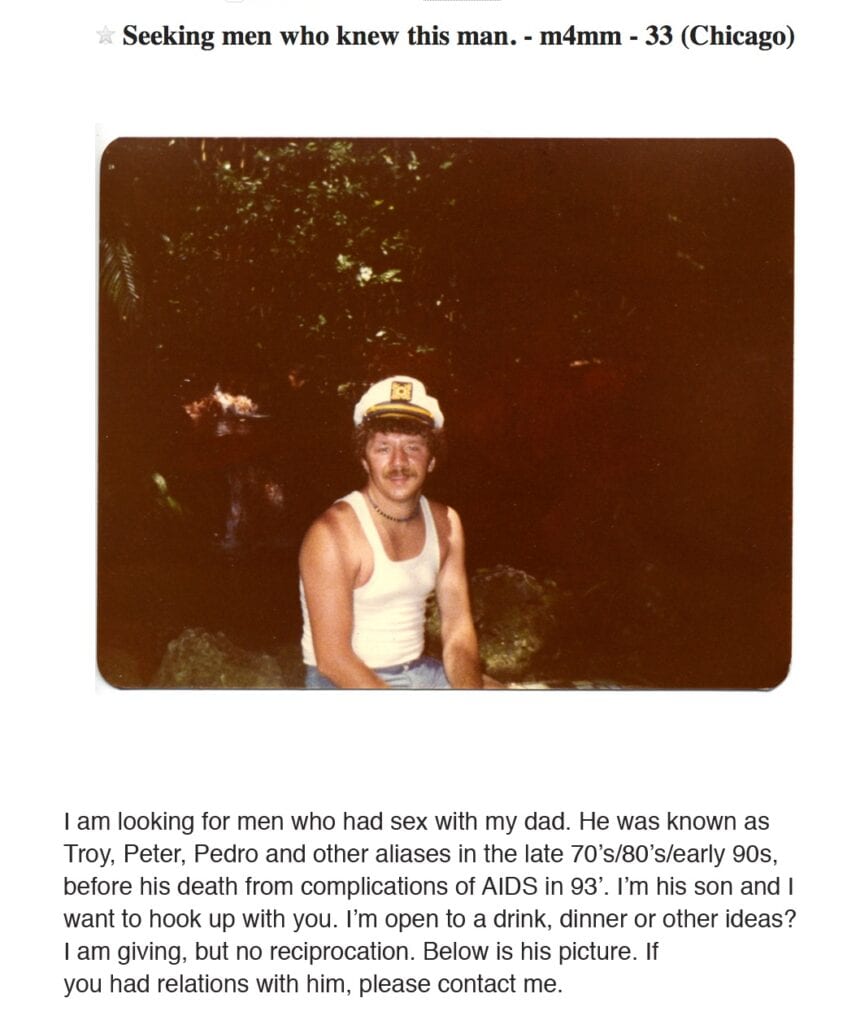

Have you had sex with my papi?

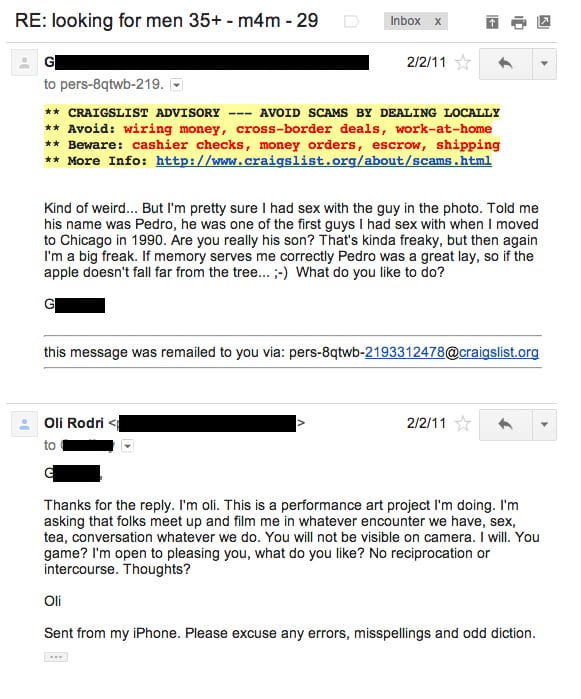

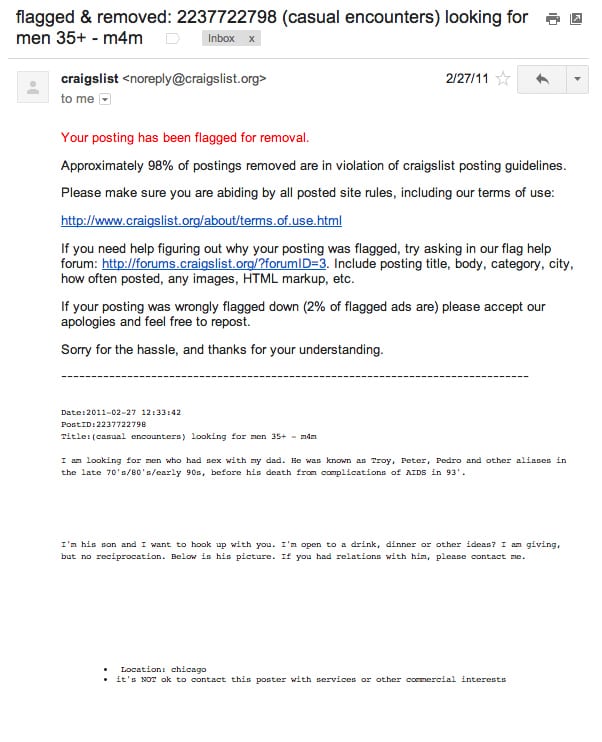

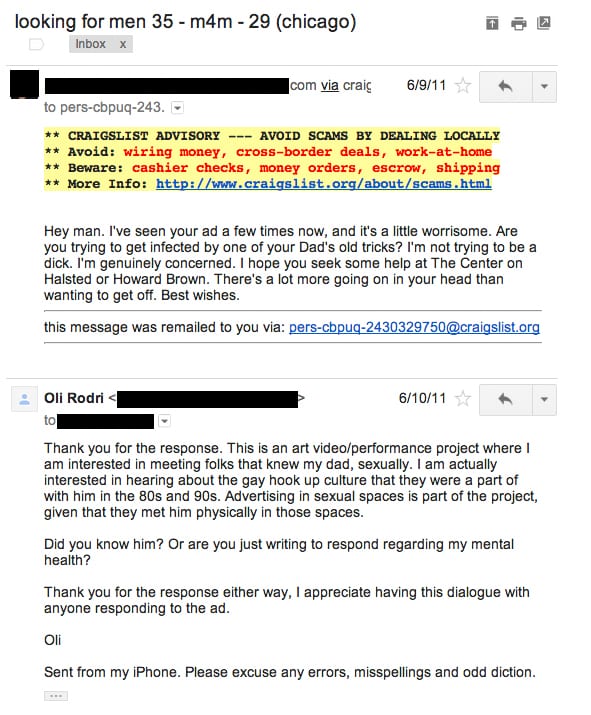

I solicited men who had sex with my Papi in 2010 on Craigslist.

Seeking to meet and hook up.

The search was destined for failure / I was expecting silence.

My Ma says, Good luck, they’re all dead.

They meaning my papis / multiple queer padre figures.

In my post, I was seeking that absence.

This absence signifies the potential teacher, father, lover,

friend that we could have loved, fought, and felt.

AIDS devastated these potential connections.

And these non-relationships are part of our daily mourning.

________

The hospice—1993 Chicago House—Now the Trans Life Center.[1]

The straight men with wives had the only room downstairs.

Leaving, moving quicker

out—

upstairs,

there was a drag queen next door.

His mother and mine fast became friends.

Both were drag queens.

AIDS is silent in its wasting kill.

Everything runs through you.

He was better now.

No, not better—

quiet.

The last time I recall him making sounds was in the hospital.

It was winter—loud-cold, bitterly dark.

There was a television in the waiting room.

I would watch Jesse struggle with HIV on Life Goes On.

Thinking about the relationship of opera and AIDS: Patti Lupone,

Maria Callas in Philadelphia.

It was so much easier to watch Jesse die a TV death

than to be witness to a real one.

The last sound he made was every liquid leaving him.

Another ending.

I am an AIDS baby, reared in an epidemic child.

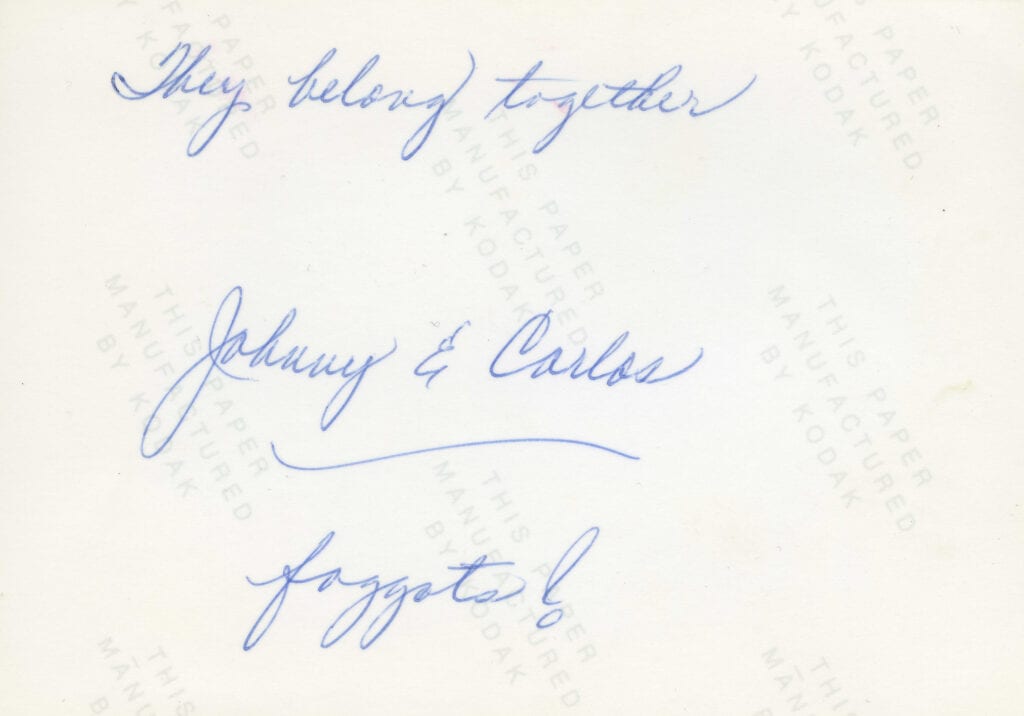

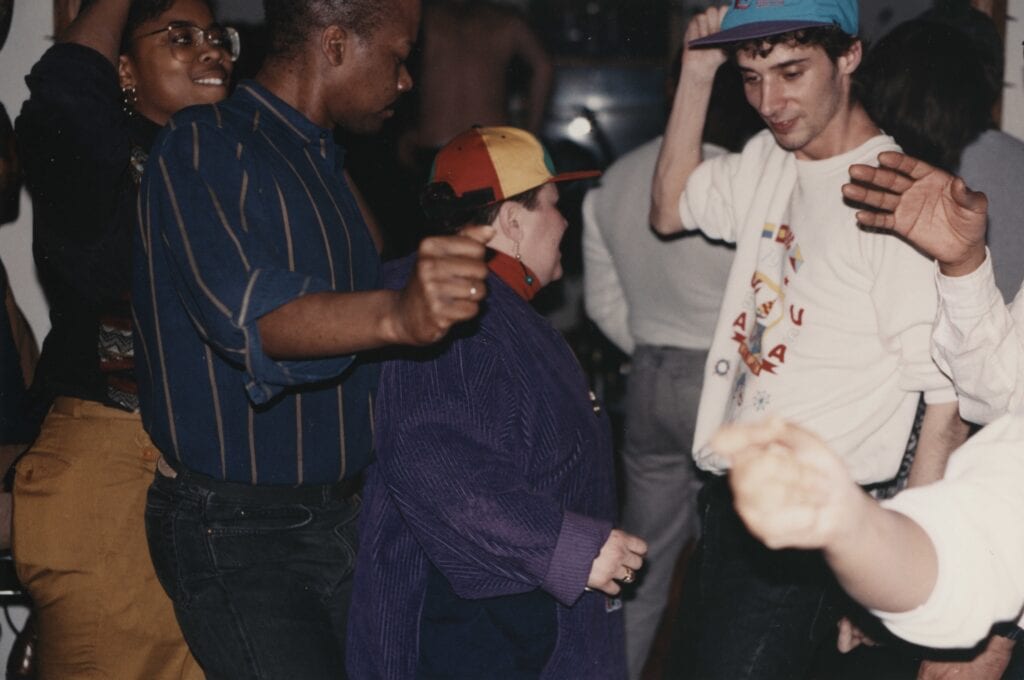

¡Feliz cumpleaños! Mi Papi throwing his birthday party

November 1987, I’m a fresh 7 years old.

He has many cruising amigos companions partners, estan aqui.

One of his drunk amigos, large mustache lips ojos

Tu Papi is a maricón / tu papi is a faggot / gay.

I laugh.

I don’t know what I’m laughing at.

I don’t know what a faggot is, a maricón yes.

I couldn’t tell what it meant either.

Somehow if it was attached to this it wasn’t that bad.

I smile at the dyke in the corner who looks like me.

Our matching fades cut to our chin.

I look around at the men queers trans* folks.

Laughing.

Drinking.

Dancing.

Hugging.Holding.Loving.Kissing.Simpatico.

Supporting one another.

The big A—as they called it—had come.

Visibly flaco sores y dehydration bags as dance partners.

If this was gay, I loved it.

Or if he was a faggot, so was I.

And so was my Ma.

My Ma is a faggot.

I’m a faggot.

We are the only two faggots left.

About the artist

Oli Rodriguez is an interdisciplinary artist working in video, photography, performance, installation, and writing. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor in the Art Department (Photography) at California State University, Los Angeles. His intersectional research and interdisciplinary projects conceptually focus on queerness, notions of passing, visualizing the performativity of gender, explorations in appropriation, performative interactions with the public as a collaborator, visualizing other representations of the AIDS pandemic while referencing historical movements in gender, racial and feminist histories. He curated the exhibition, The Great Refusal: Taking on New Queer Aesthetics, at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). He is a part of the monograph Confronting the Abject, named from the research-themed class that he co-taught with Catherine Opie at SAIC. Papi, his forthcoming publication, archives the AIDS pandemic through his queer family in Chicago during the 1980s. He also just finished his short documentary film, LYNDALE, exploring toxic masculinity, cyclical familial trauma, and queerness. LYNDALE is currently distributed by Video Data Bank (VDB). Rodriguez has screened, performed, lectured, and exhibited his works internationally and nationally.