“The so-called strength of the blood, to use a popular expression, exists, but it is not a determining factor. Just as the presence of the cultural factor, alone, does not explain everything. In truth, freedom, like a creative deed of human beings, like an adventure, like an experience of risk and creation, has a lot to do with the relationship between what we inherit and what we acquire.” (Freire, 70)

“Representations are a form of human economy, in a way, and necessary to life in society and, in a sense, between societies. So I don’t think there is any way of getting away from them—they are as basic as language. What we must eliminate are systems of representation that carry with them the kind of authority which, to my mind, has been repressive because it doesn’t permit or make room for interventions on the part of those represented.” (Said, 95)

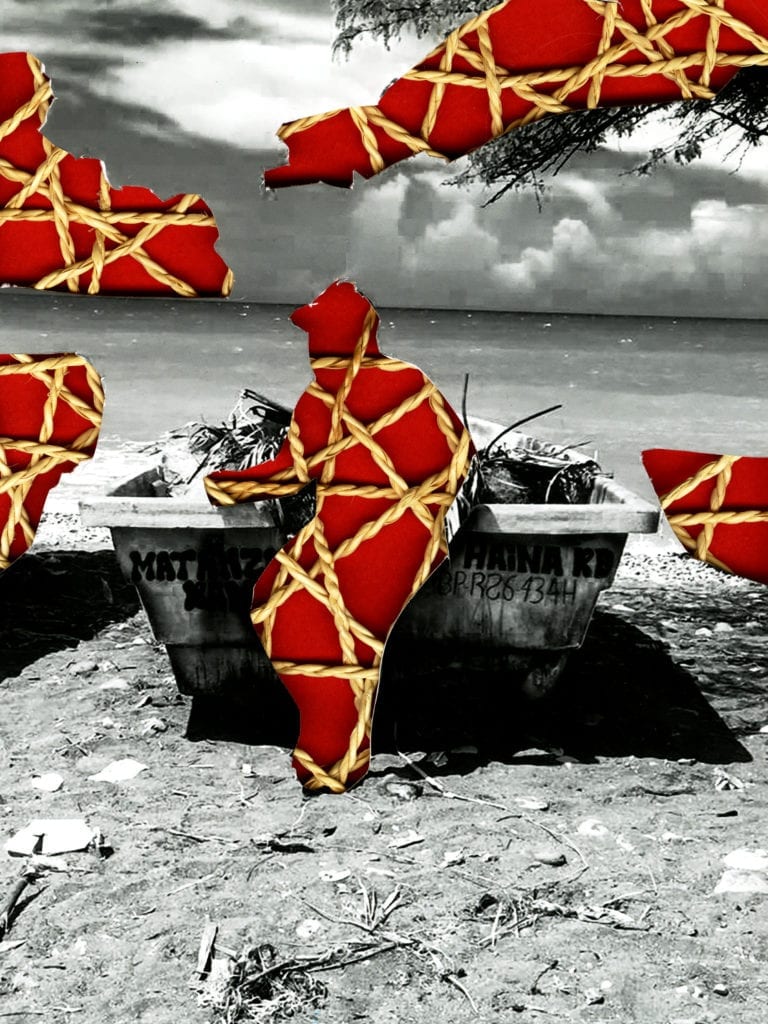

In his series Fragments of the Masculine, artist Antonio Pulgarin lays bare the complex relationship to his queer and Colombian / Latinx identities through photographs and collages composed with found objects and family photographs, specifically those of himself, his father, uncle, and stepfather. These new works—as an unrepressed system of representation—mark a specific transition in the artist’s creative explorations as he expands beyond the straight portraiture and documentary photography of earlier series including Los Banilejos, Calle 4 Sur, and Welcome to Wyckoff Gardens. The previous works were safe and accessible as reportage and ethnology to the artist’s cultural environment from Brooklyn, where he lives, to Colombia, where his parents immigrated from, and to the Dominican Republic, from where his stepfather originates.

If these earlier photographs were visual essays, then the series Tierra Del Olvido was the precursor to Fragments of the Masculine. What do these recent, more conceptual photographs genuinely say about cultural identity and queerness? The most salient qualities of Pulgarin’s latest works are a critical yet playful intersectionality as well as a deliberate performativity. Just as we get a glimpse into his working-class upbringing, the artist allows us to experience a complicated masculinizing and queering process. In that preceding series, images of female subjects, found photographs, and Catholic objects like novenas, ephemera, figurines, and prayer candles are juxtaposed to a portrait of a muscular, hirsute, fair-skinned, shirtless man of color against a light blue background. Presumably, Pulgarin even includes a campy, kneeling self-portrait in a head wrap and rosary and covered from head to toe in a black bodysuit. Here, both the homoerotic and drag further delineate qualities of queerness.

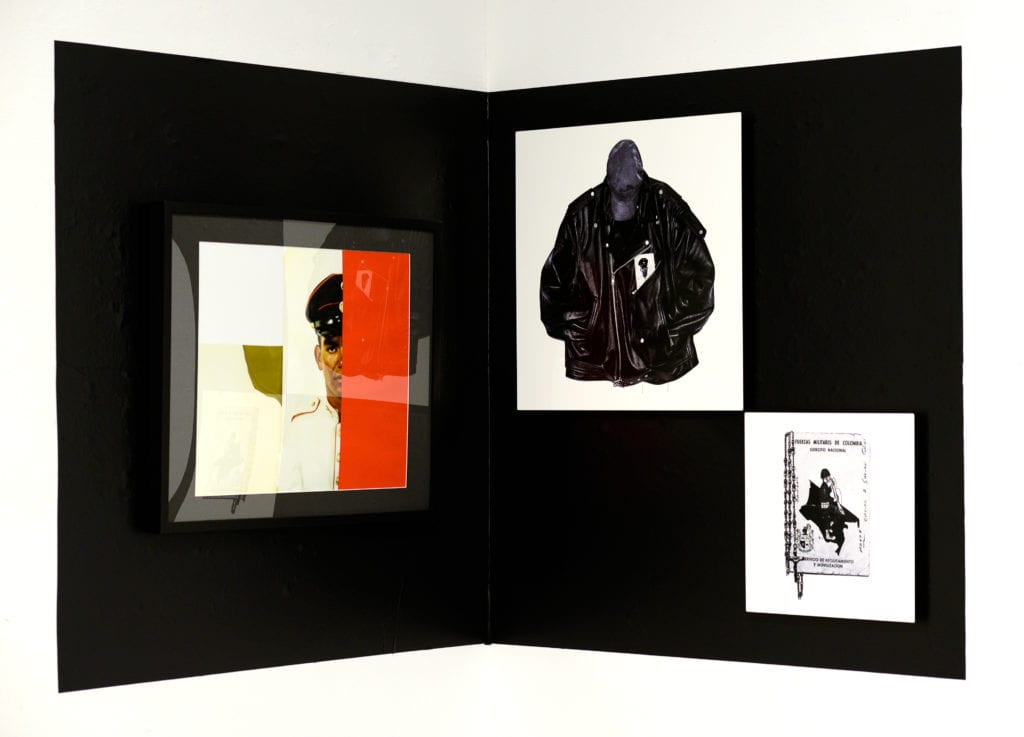

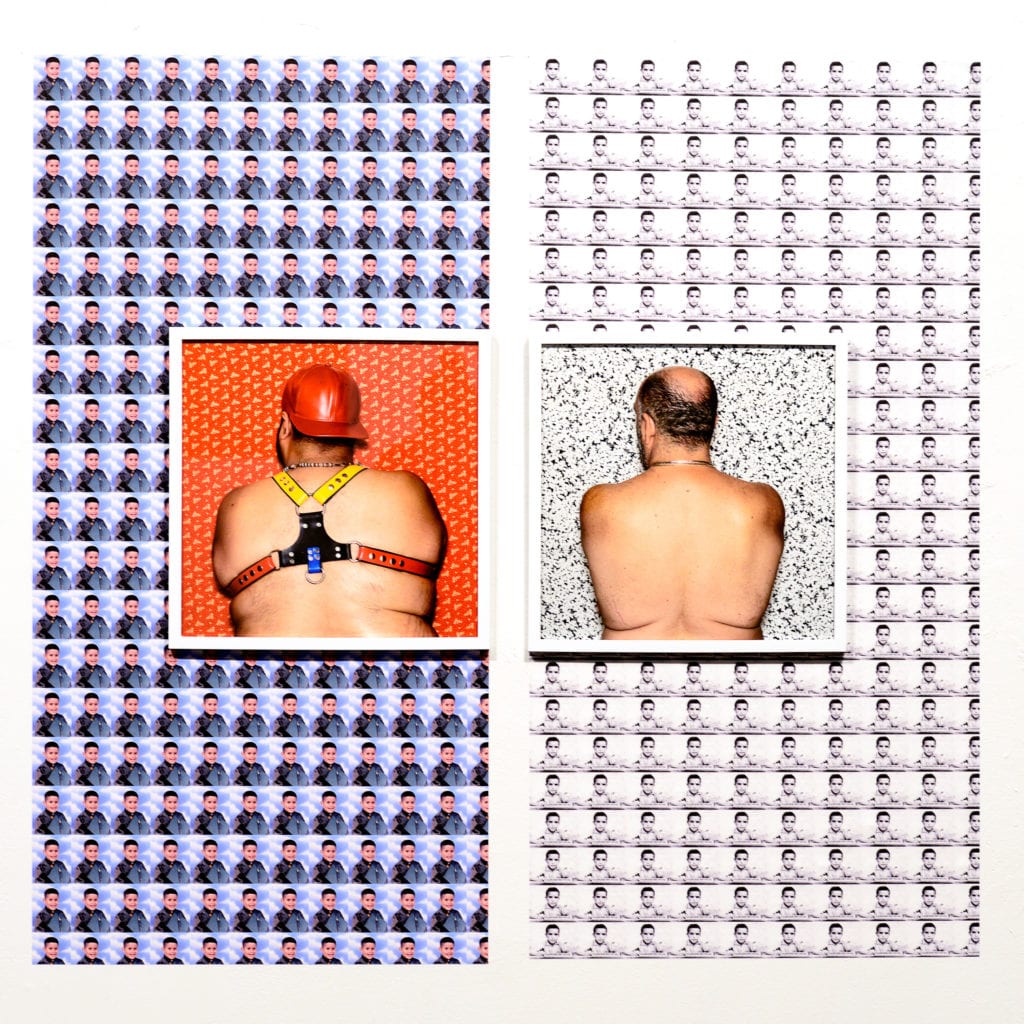

The artist potentially asserts a queer male identity, for instance, in Rebellion which presents a black-and-white self portrait of his own leather jacket and hat. Jumping out from the image, the jacket pocket carries a stunning military portrait of his stepfather, emphasizing Pulgarin’s homage and devotion to him. We also see the artist with his back to us in a leather harness in the wallpaper installation Like the Sun that Frightens the Cold. Even in a harness, the artist made the particular decision to use leather in the colors of the Colombian flag: yellow, blue, and red. As a tactic, Pulgarin Colombianizes or Latinizes queerness and ultimately provides a way to decolonize U.S.-centric definitions of queerness. What is worn upholds a culturally specific, performed and constructed selfhood that resists white supremacy.

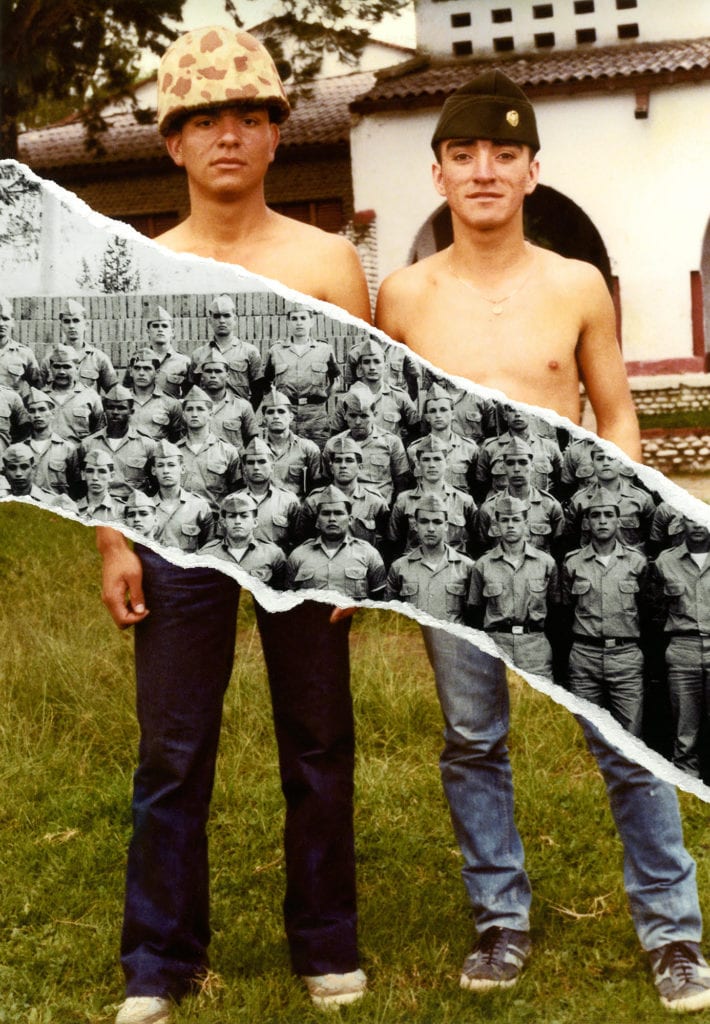

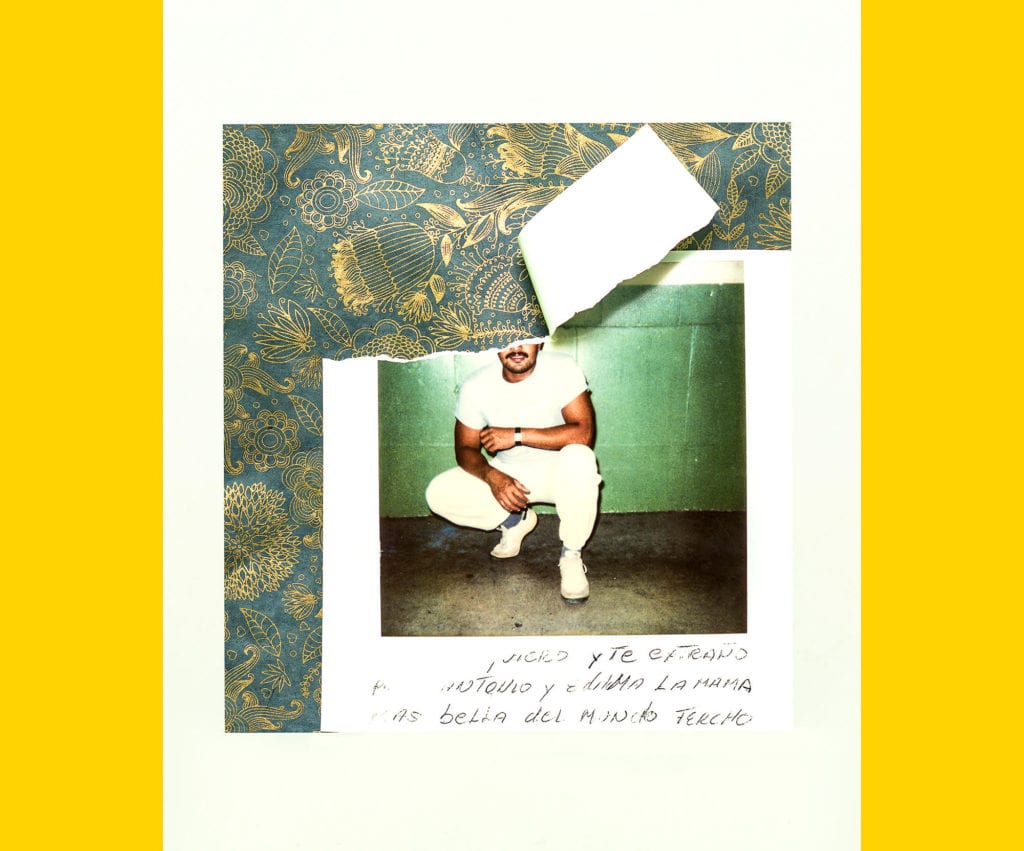

In many of the other new collages, Pulgarin utilizes the military or prison as signifiers for queerness, defining his own queerness through his relationship—real or projected—to the official military photographs of his stepfather and late uncle, as well as to the pictures of his estranged, biological father sent him from prison. Pulgarin unabashedly claims a solidarity with the homosocial environments of the military-industrial and prison-industrial complexes, a critical connection for communities of color who are disproportionately imprisoned. Images showcase or deny the erotics of half-naked men. His father’s eyes or face are obscured, declaring a clear disdain for him.

The processes used to produce these compositions were strategic and intentional including ripping, tearing, lifting, curling, unfurling, placing, framing, layering, cutting, reshaping, covering, and adhering. In certain ways, Pulgarin employs a targeted and personalized manner of representing the men in his life. These visibly physical tactics are weaponized not unlike how Edward Said has described: “…the act of representing (and hence reducing) others, almost always involves violence of some sort to the subject of the representation, as well as a contrast between the violence of the act of representing something and the calm exterior of the representation itself, the image—verbal, visual, or otherwise—of the subject.” (Said, 94)

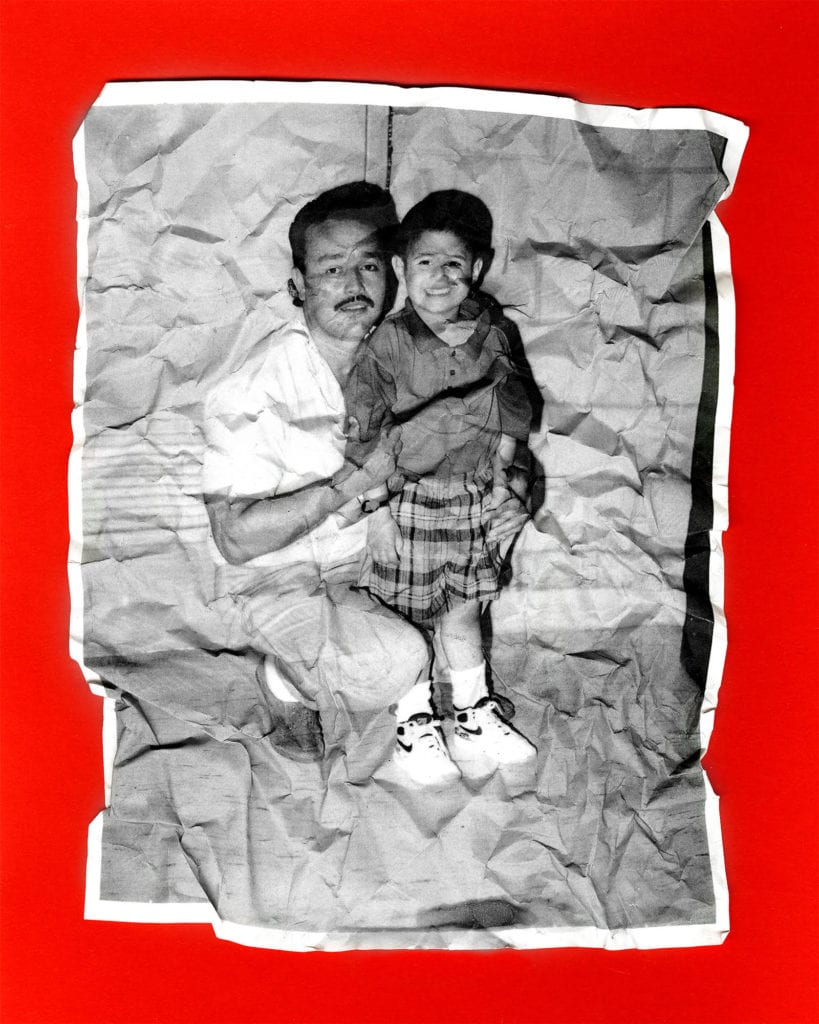

Demonstrative text overtakes the compositions of Como Ser Macho which literally begin as a question but then repeats over and over into the triptych like shouted orders. Papasito in red and white all-caps text rises above a torn portrait of the artist’s father’s oiled-down body. Red plastic grating covers a photograph of his father in a white brief. A black-and-white photograph of the artist as a young child and his father has been crumpled up then spread out to be rephotographed in its wrinkled state.

Artist Whitfield Lovell has provided an interpretative read of Pulgarin’s work which supports this queering thrust:

“I happened upon Antonio Pulgarin’s artwork in an LGBTQ exhibition at Taller Boricua, New York. I was intrigued by his use of vintage photographs juxtaposed with more recent imagery. Each work seemed to suggest a story, through the poetry he created between the various images. The piece that struck me most is The Ties That Still Bond Us, an image of a nude man sitting cross-legged on a bed, with tattoos and military style dog-tags. The tattoos and the young man’s haircut seem contemporary, yet the overall subtle color and the motel-like drapery and bedding make the timing of the sturdily built nude’s posing hard to pinpoint. There is an old, square black and white photograph montaged onto the upper right corner, of two Latino servicemen posing on an army base. The images in the accompanying black and white image feel as if a generation or more before the sitter’s time…

The sitter has a mysterious gaze that makes one wonder about who he is, and how he came to pose so modestly and without shame. Is he an eager and seductive sex partner or simply a beautiful man captured in a platonic moment, unconscious or unaware of his physical allure? Or none of the above.”

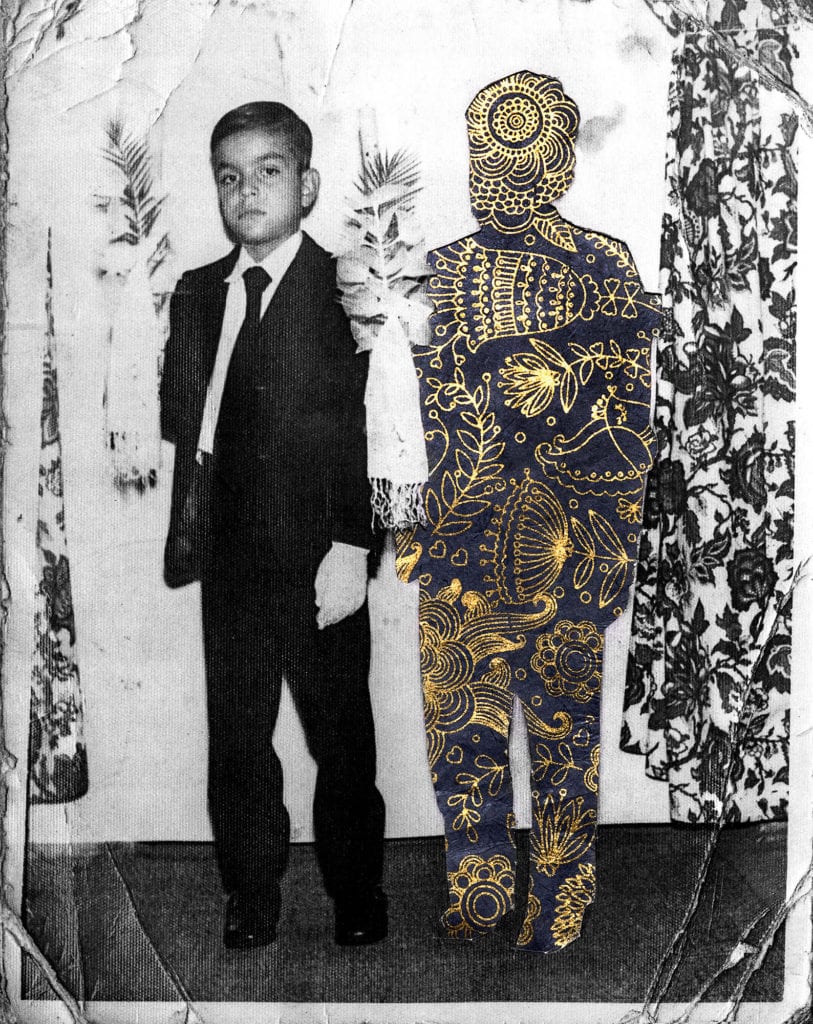

Another cultural layer is unveiled in Pulgarin’s works such as Communion 1972 and the triptych Communion 2001 which introduce the spectre of a religious upbringing. The Catholic communion images are reconfigured with amorphous bodies covered in a golden floral filigree like decorative wallpaper. These works are both ostentatious and claustrophobic, revealing possibly an overbearing or oppressive relationship to the Church, wherein identities are immersed and hidden, disallowed or ignored. Another level of violence is exemplified here and Pulgarin makes a visual representation that is both cryptic and alluring haunted by the trauma of homophobia and abuse.

“To be effective, art must exert its capacity for estrangement…Art should not help people become assimilated in the existent society, but at each turn should challenge the assumptions of that society, whether through the demands of intellectual and visual rigor and/or the heightened recognition of pleasure and pain.” (Becker, 119-120)

Altogether, Fragments of the Masculine is purposefully non-narrative and non-linear. There exists only fragments that may not really add up to anything discernible. Furthermore, the monolithic “the Masculine” is merely a westernized construction that needs to be historically dismantled. In each of these works, images are performed in so many different ways as to emphasize an emotional quality. Pulgarin engages strategies of doubling and pairing, repeating and reduplicating, triplicating, reconstructing, color blocking, and replicating oppressive text to elicit and emphasize responses grounded in empathy. For a transformative experience, we should try to feel what the artist feels and this shall lead us to build solidarity with the artist and his communities and concerns, towards revolution, our collective liberation.

About the artist

Antonio Pulgarin (b. 1989) is a Colombian-American Lens-Based Artist who utilizes photography, photographic collage, and mixed media in his practice. Pulgarin mounted his first solo exhibition at Kingsborough Art Museum in the fall of 2019. Pulgarin’s work has been featured in exhibitions at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, Aperture Foundation, Longwood Art Gallery and BRIC. His work has received honors from YoungArts, The Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, EnFoco, The Magenta Foundation, Latin American Fotografia, American Photography, and PDN Photo Annual. Pulgarin will be exhibiting his work at the Musée de l’Elyséein in Lausanne, Switzerland and at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz in 2020.

Pulgarin’s work has been featured in publications such as Vice, UnSeen Magazine, Visual Arts Journal, BESE, Slate, LensCulture and The Huffington Post. He received his BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts and is currently based in Brooklyn, NY. He is a 2019 Bronx Museum of the Arts AIM Fellow and 2020 Baxter St CCNY Workspace Resident

Sources

Becker, Carol, editor. The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, & Social Responsibility. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Freire, Paulo. “Eighth Letter: Cultural Identity and Education” from Teachers as Cultural Workers. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1998.

Goude, Jean-Paul. Jungle Fever. New York: Xavier Moreau, Inc., 1981.

Interview with Whitfield Lovell. New York: Antonio Pulgarin, 2020.

Mariani, Phil and Crary, Jonathan. “In the Shadows of the West: Edward Said” from Ferguson, Russell, Olander, William, Tucker, Marcia, and Fiss, Karen, editors. Discourses: Conversations in Postmodern Art and Culture. New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990.