For Wendy Red Star, history speaks through clothing and photographs. In her most well-known photographic series Four Seasons (2006) Red Star wears an Apsáalooke (Crow) dress akin to one that she pointed to through glass barriers during an artist talk in the Native American Art Galleries at the Portland Art Museum in 2011. Both are red and tunic length with dark blue accents at hem, wrist and neck, and arcs of elk’s eye-teeth radiate from across the chest and shoulders. The artist knows that those teeth are markers of the wearer’s significance. In a matrilineal tradition such as the Apsáalooke (Crow), the number of eye-teeth—which come only two per elk—indicate the wearer’s relation to prolific hunters or successful tradespersons. In Four Seasons (Fall), Red Star is seated in the dress beneath an inflatable plastic elk, on brown carpet, amid fabric leaves. Five years later, in the galleries of the Portland Art Museum, Red Star connects the dress displayed as an artifact behind glass and to one of similar fashion which she touches, one that might be her own. In both the photograph and the talk, Red Star uses her body to highlight the disjunct between displays of fashion as ethnographic evidence of the past and the real living meaning it carries for the Apsáalooke (Crow) in the present.

In photographs such as the Four Seasons (Fall) or Four Seasons (Spring), the artificial tableau of Red Star’s background amplifies the meaning of her satirical performance. While her attire, including the elk teeth dress, signals information about the artist’s real cultural heritage to those familiar with Apsáalooke material culture, the false “naturalism” of the setting evokes misconceptions about Indigenous people. In the Four Seasons Series, Red Star gestures toward tropes established by generations of non-Native American’s “playing Indian,” while also performing as an Apsáalooke woman.[1] In these two photographs, Red Star holds the viewer’s gaze, revealing the self-consciousness of her display and highlighting the gap between Red-Star-the-artist and the character she portrays. Looking at her looking is part of the joke. It is a critique of the inauthenticity of ethnographic photography. The Four Seasons Series highlights the absurdity of ethnographic display with a poignancy that echoes Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s 1992-1993 performance, The Couple in a Cage: Two Ameridians Visit the West, and challenges misconceptions of authenticity and cultural identity analogous to James Luna’s repeated performance Take a Picture with a Real Indian. In her photographs, Red Star brings together elements of humor, history, and material culture to make her critique of identity and representation in the United States.

Red Star is a conceptual multi-media artist who has engaged with the various markers of individual and cultural identity found in adornment since the very beginning of her career. Though she was raised on the Apsáalooke reservation in Montana, she became interested in cultural identity through the Native Studies classes she took while pursuing her BFA in sculpture. During her MFA program at UCLA, she began to think more about the role of the camera and the photograph in her work:

“While I was there, I became very intrigued with all the photo majors and the way that they worked. Some people wore white gloves and vacuumed their studios and other people ate Cheetos and cut up photos and put their prints all over them. I just really loved the way that they were working with these images. And I also loved the fact that I could tell stories with photos. So, between 2004 and 2006 is when I really started to dive into using the camera as a tool for my art making.”[2]

Since then, photography has often served as a platform for her broader artistic engagement with identity and representation, as well as a direct subject of inquiry.

But research is the churning undercurrent to Red Star’s art. Being an Apsáalooke woman is incredibly significant to Red Star’s artmaking, but it does not imply that Red Star possesses a predetermined knowledge of everything Apsáalooke. Red Star is an accomplished researcher. She has spent years in personal and institutional archives, libraries, and collections learning about the history of the Apsáalooke and the history of their representation and material culture. There she came across photographs made of an 1880 delegation of Apsáalooke chiefs by the white photographer Charles Milton Bell. These accomplished men travelled from the Montana Territory to Washington D.C. where they spent months in negotiation, eventually signing a treaty with the U.S. government. Bell’s contemporaneous portraits feature the members of the delegation in full regalia and—though vivid—offer little additional information about the sitters. Now, as part of the collection of the Library of Congress, these unnamed Crow images are available for public use in ways that can further obscure their contextual specificity. For example, Red Star identified the man on a bottle of Honest Tea as Bells’ portrait of Peelatchiwaaxpáash/Medicine Crow.

In Red Star’s series, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, the artist takes a red pen to the rest of Bell’s portraits, annotating the black and white prints with handwritten text and drawings based on her historical and cultural research. Her annotations explicate the meaning of the Apsáalooke members’ attire, contextualizing the cultural information silently contained in Bell’s images. “The beauty of looking at these portraits,” she says, “is that you see their personality and their style creating this tension between the white photographer’s perspective and that government perspective and their own individuality.”[3] In one of the photographs of Peelatchiwaaxpáash/Medicine Crow, Red Star’s arrows and text show the ways adornments iterate the accomplishments of the wearer, pointing to ermine skin on a shirt as indicative of having captured a gun and ermine skin on leggings reflecting that the wearer’s status as a successful leader in war. In Bia Eélisaash/Large Stomach Woman (Pregnant Woman) aka Two Belly, her pen creates a speech bubble in which the sitter speaks his own name, countering Bell’s lack of context. Red Star highlights Bia Eélisaash’s physical scars as well as the intricate pattern work on his vest. By scratching the surface of the photograph, Red Star helps viewers unfamiliar with Apsáalooke history and culture see what is both visible and invisible in photographs. But she also inscribes some of the particularities of the sitter onto the image, reinforcing their individuality. Yet, Red Star’s annotations are not all researched facts, some are the artist’s observations or projections. Nestled amid statements of accurate cultural context, Red Star’s subjective assertions reinforce that facts in photographs are uneven. Lending her voice to the portraits, she reflects the ways that the past exists in enduring conversation with the present.

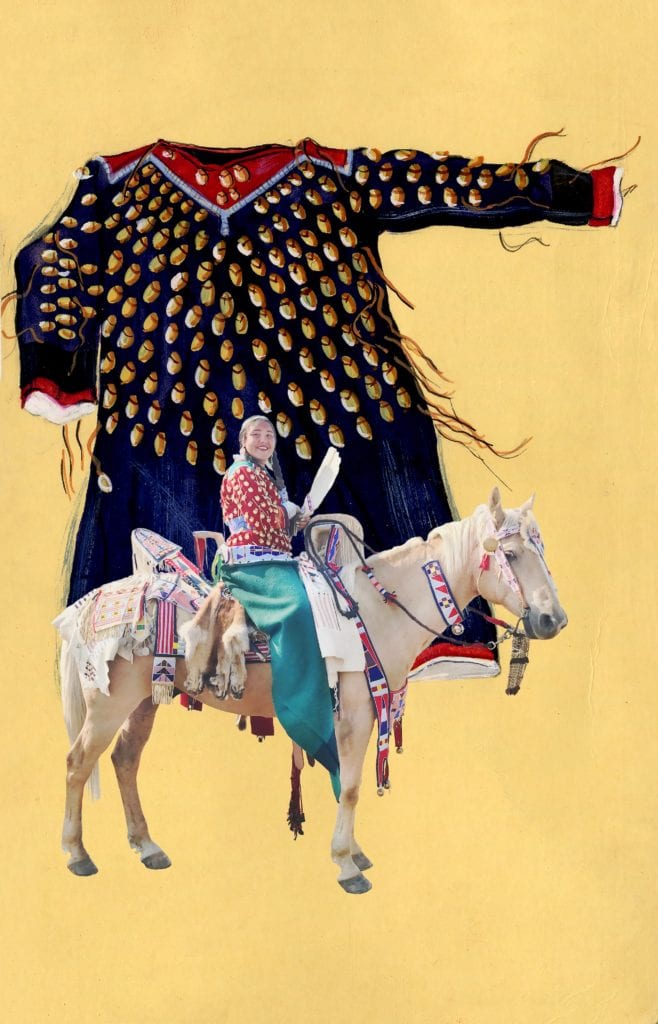

Red Star further counters lingering misconceptions of “the vanishing Indian” through large scale works that picture indigenous subjects in a contemporary context.[4] Her 2016 series Apsáalooke Feminist, features Red Star and her daughter, Bea, both dressed in elk teeth garments. Surrounded by brilliant colors and sumptuous patterns derived from Apsáalooke visual culture, as well as recognizably IKEA furniture. Mother and daughter assume poses of classical western portraiture, all the while maintaining a direct gaze at the viewer. The photographs contain rich patterns and objects that are saturated with visual information but are also extremely beautiful. In his review of Red Star’s 2019 solo exhibition, Wendy Red Star: A Scratch on the Earth, organized at the Newark Museum of Art, Vogue author Robert Sullivan remarked that Red Star’s portraits are “smart and ironic but always beautiful” and her “ceremonial Crow clothing [is] as contemporary as last month’s runway offerings.”[5] Yet, made in a year when contemporary concepts such as intersectional feminism became de rigeur, the series Apsáalooke Feminist reminds viewers that even progressive concepts are enmeshed with colonialism: “Crow is a matrilineal society,” she reminded one interviewer, “So in that regard [when discussing feminism] we are using colonial terms to describe what is a very Indigenous way of thinking.”[6] Red Star’s use of the photograph as a medium of aesthetic pleasure and cultural critique resonates with a lineage of feminist portraiture by artists such as Hannah Wilke and Carrie Mae Weems, that also traffic in both. Furthermore, Red Star’s connection to what she is wearing, through her identity, eschews the fashion industry’s legacy of cultural appropriation. Instead, she and her daughter create beautiful and confrontational photographs that are attentive to their multiplicitous identities as Apsáalooke women in the contemporary United States.

Coda: Photography as Identity

Red Star’s use of photography and engagement with the cultural significance of adornment extends beyond these few examples. We can follow the elk teeth dress up through her most recent works such as Accessions Series and Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise” (both 2019). Moreover Red Star’s rigorous artistic interrogation of identity is both prolific and nuanced. In a recent keynote the artist gave during the Society for Photographic Education’s South Central meeting at Texas Tech University, Red Star indicated her attentiveness to the effects of identities beyond the cultural. Echoing her recognition of “photo majors” as having an experience distinct from her own during graduate school, at the beginning of her talk she graciously thanked the photography community for always welcoming her and her artwork into their/our world. She also carefully admitted that, though her art has always been photographic, she often experiences waves of imposter syndrome when participating in the photography community.[7]

This statement is striking, because it acknowledges a deep attachment felt by many practitioners of photography. Many of those who identify closely with a medium, that for so long was an underdog of the art world, hold fast to it. Red Star’s comment demonstrates that identifying as a photographer is so important to so many artists that they amount to a community of individuals who care for each other and for the practice and history of the medium. But the vulnerability of her statement of feeling like an imposter among artists who identify as photographers, also speaks to the barriers or walls that are often perpetuated by the making of community and by media specificity. It is a reminder to those of us who identify as members of the photography community to take a look around and read the signs of exclusion and inclusion that we might be wearing. To thrive as a truly versatile medium, no one should be made to feel like an imposter, instead the plural reaches of photography should stand open to any artist, but especially one as virtuosic as Red Star.

About the artist

Baaeétitchish

Baaéetitchish (One Who Is Talented), references the Apsáalooke name Wendy Red Star received while visiting home. It is the original name of her grand-uncle, Clive Francis Dust, Sr., known in the family for his creativity as a cultural keeper.

Raised on the Apsáalooke (Crow) reservation in Montana, Wendy Red Star’s work is informed both by her cultural heritage and her engagement with many forms of creative expression, including photography, sculpture, video, fiber arts, and performance. An avid researcher of archives and historical narratives, Red Star seeks to incorporate and recast her research, offering new and unexpected perspectives in work that is at once inquisitive, witty and unsettling. Red Star holds a BFA from Montana State University, Bozeman, and an MFA in sculpture from University of California, Los Angeles. She lives and works in Portland, OR.

[1] For more on the significance of Euro-American’s performing as their interpretation of Native Americans see Philip Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

[2] Red Star in Sara Radin, Wendy Red Star’s Art Celebrates the Indigenous Roots of Feminism,” Vice (May 21, 2019) https://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/ywyb5k/wendy-red-star-art-celebrates-the-indigenous-roots-of-feminism

[3] Red Star in Wendy Red Star and Steven Zucker, “Wendy Red Star, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation,” in Smarthistory, March 8, 2018, accessed January 27, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/peace-delegation/.

[4] The myth of “the vanishing Indian” is linked to broader myths of the frontier as empty and “virgin” land. Perpetuated largely during the late-nineteenth century, it is a deeply ingrained cultural notion that Indigneous people in the United States no longer exist. For more on the relationship between this myth, gender, race and imperialism see Anne McClintock, “The Lay of the Land: Genealogies of Imperialism,” in Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest ( New York: Routledge, 1995): 21-74.

[5] Robert Sullivan, “Wendy Red Star’s New Exhibition Is Part Historical Corrective, Part Ghost Story,” Vogue (March 2, 2019) https://www.vogue.com/article/wendy-red-star-art-exhibition-a-scratch-on-the-earth-newark-museum.

[6] Red Star in Radin.

[7] Wendy Red Star, Keynote Lecture, Society for Photographic Education South Central Meeting, Texas Tech Lubbock, October 12, 2019.