The body is polarized. The land is spoiled. The ideals of governments are questionable. A creative mind is a definitive act towards transformation. The visibility of bodies and the properties they are capable of are achingly necessary. Now is not the time to be catatonic or complacent. The fact of the matter is that the body is capable of being a rebellion, a vision of action. In the work of Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Patricia Voulgaris, questions of rationale and the breaking of limitations feed the eyes and compositions of their artistry. These artists complicate the possible; the fingers and limbs of their works slip into viewers like thoughtful knives. Feelings unusual at first are ultimately lusciously perplexed in familiarities, desires and newness.

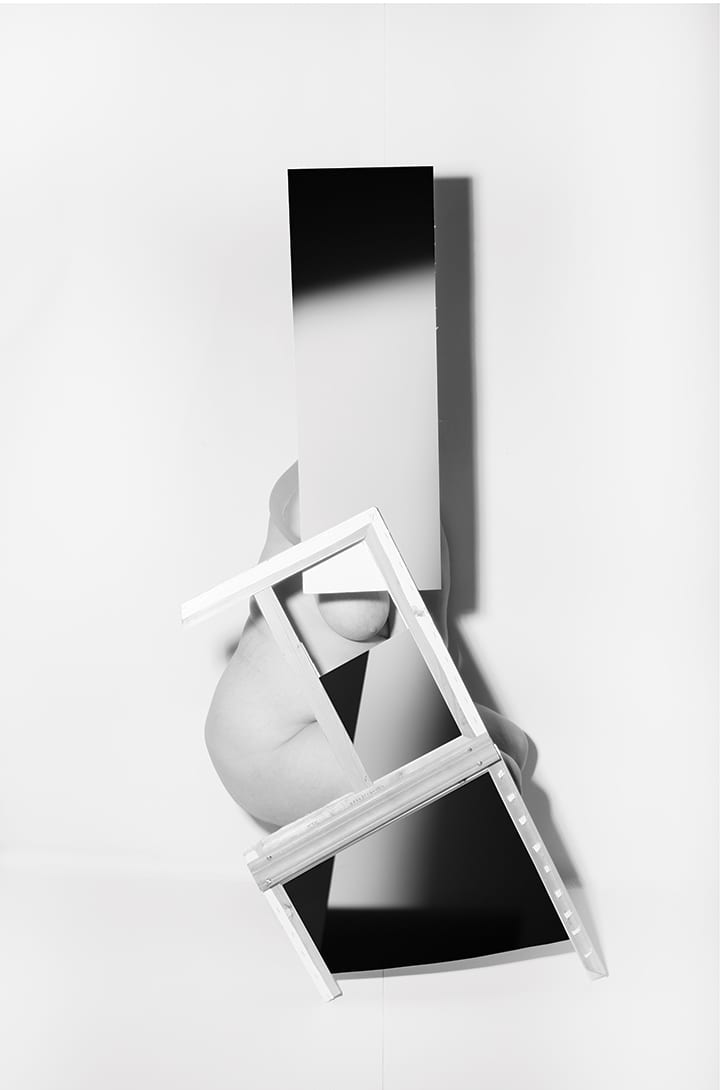

Assembled parts of reimagined objects and collaged imagery perform the constructions of Sepuya and Voulgaris’ work. These artists allow themselves to be exposed in amounts of personal flesh, but not so much as to be specific to the body. Their bodies are available to themselves and they trace in their imaginations, which allow the ideals of self to become more wonderful, less distinct, and much more peculiar. There are grimaces of meticulous choreography and sculptural decision-making. They uphold the most exciting possibility of photography—pragmatic invention.

A discussion is much like an impromptu choreography. Unlikely folks can flock to the sounds and thoughts of each other. They expand themselves and the things they feel. Culture is cultivated by being proactive and engaging the needs of an active proclivity. The body molds minds and releases the endorphins needed to exorcise the expected and the status quo. In Sepuya and Voulgaris, such joys find flight in the frames and constructions they build. Inside the body are new worlds and new possibilities.

Efrem Zelony-Mindell (EZM): The intentional construction of self is something that I’ve always been deeply connected to. Bodies—all bodies—are not merely the sum of anatomical parts. I think photography has a history of prescribing identity. There are so many expectations that cluster around what people desire and presume looking at other people. Looking at both of your works there’s a realization to push beyond any kind of assumptions. I think it would be a good place to start by asking why the body is important to your practices.

Patricia Voulgaris (PV): One of the main reasons why I started photographing my body is my desire for permanence. The viewer acknowledges my presence when I put myself in front of the camera. I’m not interested in creating work around my reflection. The person looking back at me doesn’t exist. I transform my body until it becomes unrecognizable and genderless. My practice is centered on using the body as a form and exploiting its transformative properties that are controlled by the spaces that hinder us.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya (PMS):My work is grounded in portraiture, of those with whom I share friendship, and desire, and creative exchange. It always revolves around self-portraiture and my own touch, manipulation, and presence both materially and authorially. At times the body is more or less present in the final images but its traces (as stand-ins) are as strong to me as straightforward representation. I’m not interested in prescribing identity, and I try to resist that as much as possible. Instead, I’m going for a loss of rationality within erotic, bodily excess.

EZM:Often, creative thinking and making something visual is full of complex contradictions. The absurdity that you both speak of plays into vastly opposing parts that are present in your works, and in many ways absolves specificity and allows things to come together. You both seem to nurture certain kinds of familiarity so you can build them up and in a visually transgressive way, turn expectations on their heads. Do fears of the self or environment play into your thinking?

PMS:I don’t quite follow the question, or the thought on contradictions and the absurd. As for familiarity, yes, I do repeat and build on actions or methods that repeat. A setting or ground, a camera, and a subject either presented or reflected, and other photo-material that may intervene. Can you also elaborate on what you mean about fears of self or environment playing into thinking?

EZM:In the case of your response, Paul, you mention “loss of rationality” and Patricia spoke about becoming “unrecognizable,” but you’re both using yourselves in your imagery. The humanly impossible, or the absurd, seems innate in the work you each make. I’d argue that there’s a fascinating and extremely relatable contradiction in balancing the human and the impossible. Allowing yourselves to work with these ideals sounds deeply personal. I wonder if there are uncertainties that either of you are trying to expel or expose about yourself, or if there are experiences in the world that you see and are trying to push against. I’m always curious to know if there are kinds of motivating insecurities or threats that stimulate an artist to make their work.

PV: Physiology, memory, and environment play a huge part in my work. In my practice, the environment I work in heavily influences my work. It’s comfortable to gravitate towards the familiar. In a lot of ways comfort becomes the base in each of my images, similar to the nature of memories. I believe that memories and environment play a huge part in what makes us human. I don’t see myself as a concrete form but instead an abstract one. What you see in front of you is a piece of me, a small glimpse into my insecurities. I don’t fear criticism, only the limitations I place on myself. The real challenge lies in how we can break these limitations and insecurities we place onto ourselves. Francis Bacon once said, “How can I take an interest in my work when I don’t like it?”

PMS: I love that Francis Bacon quote, Patricia. I’d not heard it, but I think about that idea a lot. My insecurities in image-making are tied to how far I can go, and what’s the proper interpretive or abstracted distance between motivation and the resulting work, or to say it directly, explicitness. Can I say exactly what I want? And is my own interest enough?

PV: I often have the same problem while making work. Sometimes I think I should quit making photographs and try another language (painting, etc…). Regardless, making art is a process that we each treat differently and I think that’s the beauty of it.

PMS: It’s the problem of the photograph in some ways always being a document. Of being too much? That’s one reason I incorporated a surface (the mirror) that can’t help but record touch, interference, interpretation. And cutting, recombining and “collaging” of image materials on that surface help to get to that other language, maybe something between the idea of owning every word you put down on the page or line in a drawing with the thing of photography—the photo always includes what was next to the desired object, what you can’t help but get in.

EZM: Abstraction comes into play where you each reimagine parts and ideas. There are lots and lots of layers with just a peek of something from underneath or behind that lets viewers know that there’s something else going on. Neither of you give the whole thing away; we don’t need to be given everything, just enough to invite us in and have a look around. The works feel like they may be trying to reanimate something that’s been lost. The complexity and overlaps as well as the relationships and connections between different fragments are fascinating. The works feed individual narratives similarly to how stories or poems are constructed and read. How do you know when a work is finished?

PV: Truthfully, I feel that as long as I am creating work, nothing is finished. Or maybe this is my lack of confidence speaking. I believe that an artist’s death is the ultimate “finish.” The individual in possession of the works of the deceased artist is responsible for portraying an accurate representation of the artist. Can the artist be promised that their legacy will remain true and intact? This can never be certain in an unstable and unfinished world.

PMS: Nothing is finished until the idea is finished, and that may as well be death of some sort. Works get finalized, editioned, framed, and sent out into the world but they come back and teach me things in unexpected ways. I very much believe in what Brian O’Doherty says in Studio and Cube, something along the lines of, “as long as an artwork is within reach of its author, its open to revision.” I use and re-use material, fragments of pictures, sometimes re-contextualize previous works as pictures within later pictures. Lyle Ashton Harris’ installations are also a good reference for me, in that he re-incorporates and re-arranges material from scraps and notes to framed works in new and exciting iterations. Everything is open to being made over, as long as it remains within his touch.

EZM: There’s a scene from Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox that comes to my mind here. The three main characters’ tree has been destroyed and there’s a voice-over as viewers are directed to look at the hole in the ground. The line says something to the effect of, “The tree we made into a home is gone, and the same one will never grow back. But that’s ok because one day, something will.”