It seems to me you’re different from most of the boys that come to me. Most of those boys are troubled and confused. I’d say you know exactly what you want. […] But I bet you got one thing in common with those other boys. I’ll bet you’re lonesome.[1]

One month before the Stone Wall Uprising of 1969, the momentous spark that would ignite the gay liberation movement and introduce mainstream media and culture to queer politics and visibility, John Schlesinger’s film Midnight Cowboy was celebrating its New York City premiere. Despite its X-rated status, this film was distributed in theaters around the country, where it would be viewed en masse by a socially conservative America, exposing audiences to complicated issues surrounding class disparity, sexual liberation, queer life, and masculine identity.

In the film, a handsome Texan by the name of “Joe Buck” makes his way to Manhattan, dressed in rhinestone cowboy regalia, with dreams of striking it rich as an escort for the city’s most well-to-do women. Upon arrival and to his dismay, Joe discovers that his cowboy appearance and persona are comically unappetizing to New York’s elite femme clientele and is instead almost exclusively appealing to gay men. Struggling to make ends meet, Joe finds himself doing trade with lonely college boys and closeted priests in dark theaters and drafty motels on 42nd street. Following each Times Square rendezvous, Joe’s distress mounts as he grapples with a crisis of identity and with his stubborn attachment to the Western attire that serves as a come-on to gay men. When confronted by his friend and studio-mate, Rico, about these encounters, Joe emphatically argues that his cowboy get-up is aligned with the images he’s seen in books, film, and television: images of ruggedly independent men who are as straight as he is. His being an object of desire for gay men doesn’t make sense. It’s a fluke. It isn’t the West; it’s New York City. What Schlesinger’s character doesn’t want to acknowledge, or at least is unable to accept, is that the iconic archetype that has shaped his views of masculinity is a relic of the old West. His own performance of cowboy masculinity is imbued with qualities that blur boundaries between fragility, femininity, loneliness, stoicism, machismo, and sexual desire.[2]

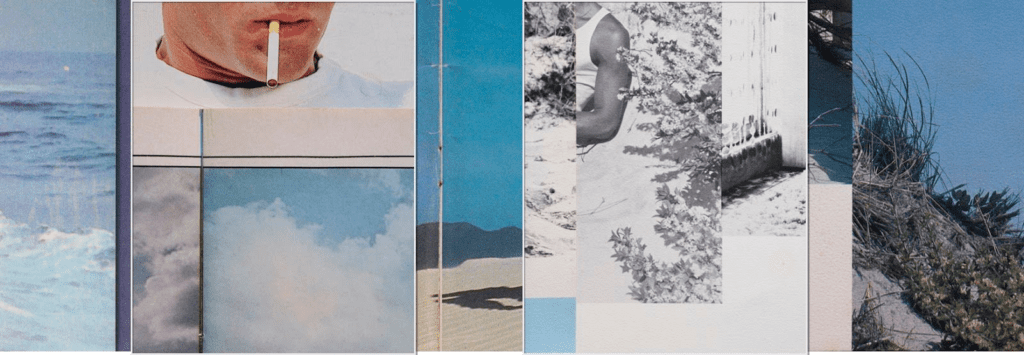

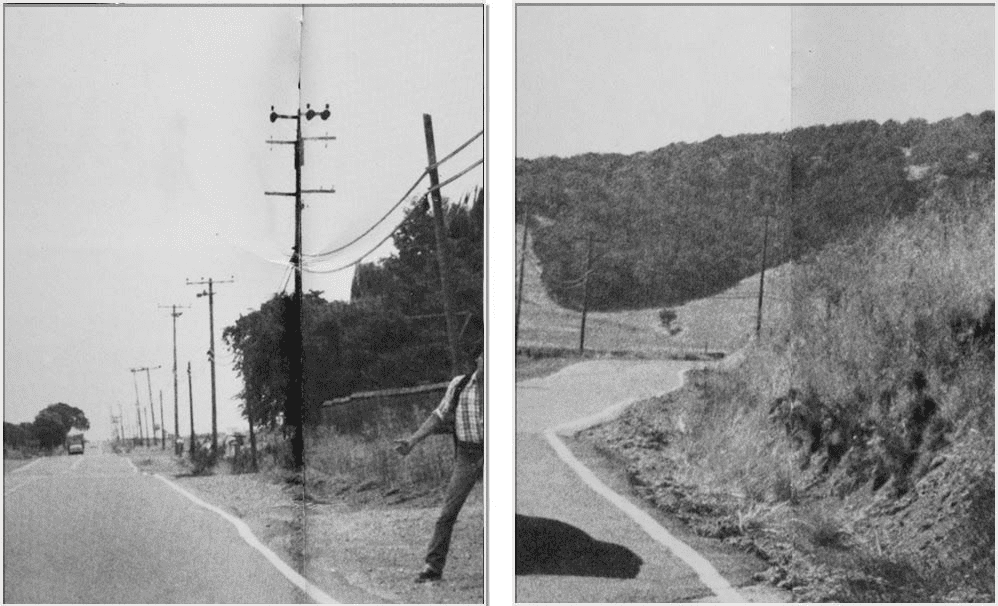

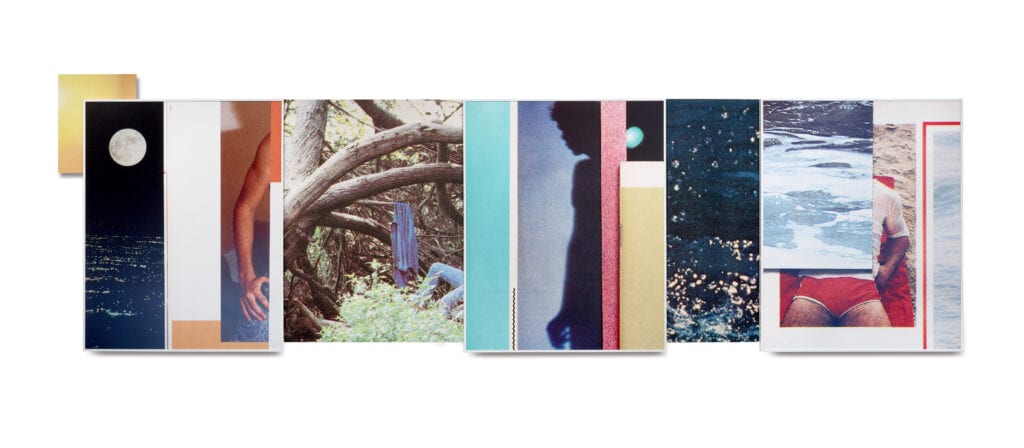

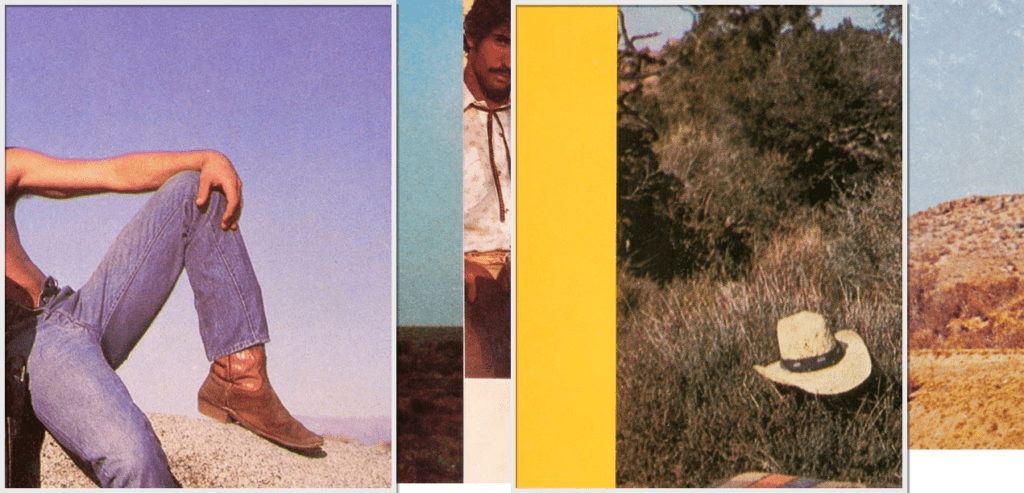

Working with the cowboy imagery that was circulating the year Midnight Cowboy premiered and throughout the two decades that followed, Pacifico Silano considers the American archetype through a new lens. His exhibition, Cowboys Don’t Shoot Straight (Like They Used To), is a meditation on tropes of masculinity as they are circulated, performed, and represented in commercial media. In response to the invitation to present a new body of work in Texas, Silano focused his attention on the iconic representation of the American cowboy, utilizing images culled from gay pornographic magazines published between 1969–89 that feature scenes of men outfitted in western clothing, set against open prairie and rural themed backgrounds. To create his works, Silano re-photographed these magazine spreads, tightly cropping, cutting, and layering images to highlight or obscure specific areas within each pictured scene, and then assembled the individual photographs in a cinematic tableau that juxtaposes atmospheric images with photographs of posing subjects, auratic objects, and romantic landscapes. Each photo assemblage in Cowboys Don’t Shoot Straight presents a complex narrative that weaves together histories of the queer community and gay visibility in the twentieth century with mythologies of the West that are foundational to a heteronormative American cultural imagination. Central to this Western mythos is the figure of the cowboy: a lonesome itinerant laborer who is characterized by his lust for danger, fierce independence, and knowledge of the land. These traits are embedded within every clichéd representation of the cowboy, from boot to bolo, and utilized in every avenue of Western pop culture to signify heroic machismo. They are traits and symbols developed and refined over time to exclude emotional and homosocial aspects of cowboy culture. Neither John Wayne nor the Marlboro Man are ever depicted as vulnerable on cold lonely nights away from their home and the people they know. They do not speak of their gaucho companions who work alongside them on the ranch. They never complain of saddle sores or sunburns. These are manly men. But what happens when this limited iconographic imagination is expanded to include the affective aspects of the cowboy and Western culture? Silano answers in his exhibition: the cowboys remain as manly as ever. It’s the definition of masculinity that evolves.

Silano explores this evolution of masculinity, in part, through the use of source materials that have historical significance in regards to the medium through which male representation was circulated and by utilizing images created at the height of the gay liberation movement. As gay rights activism and protests garnered attention in cities across the country, gay magazines were also playing an enormous part in the formation of gay public life, identity, and culture. They provided subscription-based access to queer imagery, news, and information to gay men living outside of the major metropolises where these publications were made and where semi-formal, somewhat openly gay communities and networks existed.[3] The prominence of and attachment to the cowboy model and Western motif in the picture galleries of these magazines can be viewed as a metaphor for the experience of those readers who felt otherwise detached from the gay community-at-large (and those who could not be openly queer). And the notion of desire–the allure/relation that demands recurrence–for this character becomes complex in this regard, as an attraction to butch masculinity retains its relatable attachment to affective experiences of cowboy life. In these pages, the cowboy is not only rebellious and independent but also lonesome and introspective. He is not only working on the range, but also living at a distance away from his home and community. Despite his lone-ranger depiction on the silver screen, the reality is, a cowboy is a man being manly with other men. In opposition to his status as the hetero-hero in mainstream culture, gay magazines positioned the cowboy as a central character in the representation of contemporary gay life – drawing parallels between established symbolic paradoxes and creating space for queer autonomy within a broader cultural conscious.

The entanglement between cowboy motifs and the cultural issues and movements of the sixties to the eighties in Silano’s work appears not only in the form of symbolic representation, but also through the artist’s use of framing, blocking, and spacing as well. Silano does not blur or hide the dividing lines of the picture frames that he uses, the seams in the paper, or the shadows that separate layered images from one another. Instead, the artist treats each (re)photographed magazine image as part of a complex visual narrative. In his work Ride The Wind (2020), for example, the artist places the two (very butch) male models at a distance from one another, separating them using strips of color and images of desert plateaus and prairie vistas. Each brawny model is presented within their respective frame alone. Any companion that may have complimented the men in the scene has been cropped out. Enormous skies, endless horizons, and voids of color surround the models from all sides. These spaces–these interruptions–between the two bodies infuse the work with melancholic poetics of desire and a longing for connection. All the loaded metaphors and motifs attached to American cowboyness that exists with the frames, the lonely cowboys, their weathered Western wear, the unfurled picnic blanket, are suspended within a state of being always-in-proximity-to the larger narrative represented in Silano’s work. One can imagine how the reader of the original magazine could relate to this paradoxical state of feeling so close to the worlds depicted while also feeling far removed from them. Silano’s treatment offers this experience to his viewers. He creates space to illustrate the ways intimate relationships can be formed through and by distance both physically in regards to the self (the viewer/reader) and the collective (the community) and temporally when considering how these images fit into broader queer histories and cultural narratives of masculinity.[4]

Nothing Fades Like the Light (2020) focuses on the soft and romantic qualities of cowboy masculinity, featuring beautiful images of glowing sunsets, a sun-streaked face, and bucolic wilderness. Here the tropes of Western culture appear in their most vulnerable forms: vast spaces where introspection occurs, moments when the gaze of another catches the eye, and hours of the day that signal the coming of the night. These are moments often withheld in mainstream depictions of the cowboy, or at least only presented as precursors to sensational danger: narrowed eyes meeting before a draw or dusk instigating hurried preparations for the impending dark of night. But the aesthetic qualities of Silano’s presentation quell any such cinematic suspense, offering in its place quiet images that inspire tender moments of reflection. It’s the faded hues inherent to mid-century film photography and the appearance of plotter dots and film grain that instill the work with this memorative atmosphere and imbue it with melancholic nostalgia and introspective reflection. This quality of reflection is what complicates the reading of the work, presenting an occasion to look at spaces that signify contemplation while also offering a moment to reflect on the time within which these images were made and published. Reflection is also what destabilizes the machismo of the cowboy imaginary. It’s what transforms the lone ranger into the lonely ranger. In order for these moments of reflection to occur, one must have the desire and ability to see oneself in relation to their position in the world – a difficult task for cowboys (or anyone else for that matter). Silano alludes to this in the far-left frame of the work wherein a man’s hand angles a small mirror in the direction of his body. In the mirror, a void.

The parentheses that separate “Like They Used To” from “Cowboys Don’t Shoot Straight” in Silano’s exhibition title highlight the evolving nature and fracturing of cowboy symbolism throughout its historical representation in media. Borrowed from Tammy Wynette’s 1981 song of the same name, Silano uses this tongue-in-cheek title to reflect on the ways in which queer histories and portrayals in these magazines altered the signifiers that were once reserved for heteronormative icons. As these signifiers and motifs were adopted by gay culture, their symbolism was transformed, as were the concepts of masculinity. The significance of this transformation relates directly to the activism happening during the time within which these images were made. The broadening of queer vocabulary and visibility in media in the sixties through the eighties to include a canonized figure such as the cowboy–the utmost symbol of American machismo–is a testament to the way mainstream culture can become more inclusive. Gay magazines recognized just how much Western traits rely on their repeated performance. They recognized that every performance is open to interpretation and translation. They recognized that by including these images in their magazine pages that some cowboys didn’t have to be lonely, or at least that gay men who might feel alone or emasculated by their portrayal throughout the history of mainstream media, could, at last, see themselves and their community in these pages. Silano’s tableaus are a testament to these histories. They bring these conversations into the present, offering a moment to consider how these concepts and their assumed boundaries might continue to change and grow.

About the artist

Pacifico Silano is a lens-based artist whose work is an exploration of print culture, the

circulation of imagery and LGBTQ identity. He received his MFA in Photography, Video

& Related Media from the School of Visual Arts. His work has been included in group

exhibitions at the Bronx Museum; Tacoma Art Museum; Oude Kerk, Amsterdam; and

Museo Universitario del Chopo, Mexico City, and will be part of the group exhibition,

Fantasy America, opening at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in

March. He has had solo shows at Baxter ST@CCNY, The Bronx Museum of the Arts

Block Gallery, Rubber-Factory, Stellar Projects, NYC and Fragment Gallery, Moscow.

Reviews of his work have appeared in The New Yorker, Artforum and The Washington

Post. Awards include the Aaron Siskind Foundation Fellowship, NYFA Fellowship in

Photography, and being a Finalist for the Aperture Foundation Portfolio Prize. His work

is in the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art.

Visit his website at www.pacificosilano.com.

Notes

[1] John Schlesinger, Midnight Cowboy, May 25, 1969; New York, NY Jerome Hellman Productions, Mist Entertainment, United Artists, film.

[2] Midnight Cowboy is a milestone film in regards to its honest (albeit narrow and fragmented) portrayal of queer life in New York City. For many gay men, this was the first time they would see queer life represented openly and with purpose in a mainstream Hollywood feature. For an in-depth examination of the film Midnight Cowboy and its relationship to queer culture, representation in media, and relation to capitalist ideology, see: Kevin Floyd, “Closing a Heterosexual Frontier: Midnight Cowboy as National Allegory” in The Reification of Desire: Toward a Queer Marxism, 154-194 (Minneapolis: University Minnesota Press), 2009.

[3] These short sentences do little service to the immense research and writing on the topic of gay publishing and the formation of gay public life, queer politics and identity, and visibility in the U.S. See: Lucas Hilderbrand, “A Suitcase Full of Vaseline, or Travels in the 1970s Gay World,” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol 22, no. 3, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), 373–402; David K. Johnson, “Physique Pioneers: The Politics of 1960s Gay Consumer Culture,” Journal of Social History 43, no. 4 (2010): 867–92; Rodger Streitmatter, Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995), 183–210.

[4] This interpretation is inspired by Alejandro Cesarco’s essay Under the Sign of Regret, see: Alejandro Cesarco, Under the Sign of Regret, PhD diss., Lund University, 2019.

The title of this essay is borrowed from Arthur Russell’s song I Never Get Lonesome from the album Iowa Dream (Audika Records, 2019). This song is part of a collection of remastered and re-edited demos recorded by Russell in the late 70s and mid-80s, before his untimely death from AIDS in 1992. Russell is well-known for his contributions to disco and experimental composition, but his roots in Iowa influenced a number of country-inspired tracks that feature witty lyrics and unusual arrangements set to well-trodden country sounds. For me, these tracks are exemplary of the artist’s ability to queer genres. To learn more about Russell, see: Tim Lawrence, Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-92, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009).