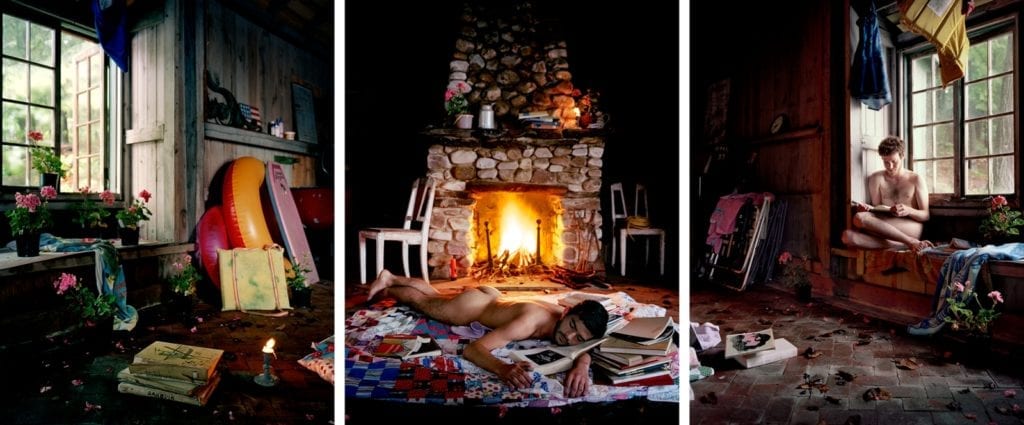

David and I met when I was a student at Massachusetts College of Art in 2004. Years later, I went to his lectures in Provincetown hoping to reconnect. In the summer of 2010, he asked me to assist on one of his shoots photographing a young man in a parking lot. David made a picture of Eric Bryant that day. He and I fell in love. Eric and I have been together from that moment. David went on to make his project The Tale is True in our home and helped with the cleanup. Since then, David has become part of our history, our family, and the seaside place we love so much. His exhibition, Chosen Family, opens at Houston Center for Photography on May 11, 2018.

Leah Dyjak (LD): We have known each other a long time in many roles, first as student/teacher, then as photographer/assistant, and now as dear friends and chosen family. I was very struck by something an old friend of yours shared with me. He said that you have a habit of arranging everyday things to make them look extraordinary. I hear you can make anything look good. This habit seems to carry into your photographs. Can you tell us a little bit about your background? Are you really always setting the stage, if you will? Is there room for collaboration in your picture making, or are you steering the ship most times?

David Hilliard (DH): It’s a hundred percent true, and I would also turn it on you a little bit because I think we have this in common. We want life to imitate art. This is a good question because I grew up lower middle class, you know, kind of poor. I was surrounded by people whom you could say were often materialistic. My father always had his study set up a certain way with all his precious things around him and all the books that he wanted at his fingertips. There were snacks here and the cigars there. He used to call it his nerve center. Everything was curated, for both visuals and functionality. My mother on the other hand lived in a slightly upper-class, suburban place. She had her curio cabinets, everything matched. My grandfather had a bar in his basement. It was like this fantasy space. It was not just a home bar. It was made to look like a real bar that one might find in a public space. There was a sense of how things looked that mattered when I was growing up. I think this is what started my interest in the curation of space. But it’s also bigger than that; I loved how things looked in movies and theater, too.

I always have an idea of what I want in my pictures. Some of my favorite pictures, both in my work and in the work of other artists, happen from something serendipitous, some kind of fusion. The best art is a kind of surprise. If you’re dealing with another person, their energy is colliding yours, or the weather could be doing something weird. You have to think on your feet. For all of the control I have in getting the picture that I want, I remain open to surprise and change, but still make a version of the work I want, if that makes sense.

LD: Yes. that makes sense. And it also brings me to the next question: I have always found the details and use of natural light in your images intoxicating. It is like I have been seduced first by the mise-en-scène, and then by your subjects.

DH: I think if you’re an artist, especially a visual artist, you’re always working with light. I grew up around photography a little bit, so I understood how light works in pictures. I got into more lighting in graduate school. I have to talk about Gregory Crewdson right off the bat. He’s the master of a manipulated kind of theatrical lighting. A lot of my early work was heavily lit. In the end, I became disinterested in it because I felt there could only be so much artifice going on in my work—the multiple panels, the performance, the shifting focus, all that stuff. That, coupled with how I love the way natural light looks, eventually caused me to strip it away.

LD: How do you come to choose the people you photograph? Are they always close to your heart in some way? Or is it a desired intimacy?

DH: All the pictures are about intimacy in some way, either longing for intimacy, an actual intimacy, or a surrogate for intimacy that once was. A lot of my work is really just wanting to make connection. It may be in the form of a more spontaneous photograph, a more staged photograph, a photograph of an intimate friend or family or a total stranger. I think I’m kind of lonely at times and photography feels like the kind of intimacy that I long for. I think a lot of artists would say that. There is a desire to express intimacy within my work and I think this exhibition Chosen Family will showcase that quite well. I photograph my extended family and close friends. I try to celebrate the best of them. This can be difficult at times, especially when I’m looking at my mother’s world, which is very Christian; it’s basically a world that does not accept mine. The work with her is a bit critical at times, but still looks good. The light is flattering and everything initially appears “okay,” yet there is a tension. I am attempting still to be somewhat objective while trying to tell her story, but I have to keep my opinion alive in there somewhere. So, there’s that, and there’s also my images of total strangers. Within them, I try to celebrate what I think I am experiencing—their psychology, or maybe projecting mine onto theirs. I often photograph younger kids as surrogates for my own youth, full of memories of intimate moments and a desire for connection.

LD: That is a beautiful description of the faces in your pictures and leads into my next question. Each of us can construct narratives around our families. I think we paint a picture that we can live with every day, both for ourselves and others. Would you consider the images in this exhibition a complete narrative for you about chosen family? If not, what is missing?

DH: I think that many of the photographs do represent family. I think there’s a good selection of my father’s left-leaning, East Coast existence that aptly describes his world. There is also a good representation of my mother’s Evangelical Floridian world.

LD: Then there’s other men.

DH: Yes. So, there is definitely my family, pictures of flesh and blood genetics. I have that family, but I think there’s also a good number of photographs of my friends and lovers. There is a queerness in them and myself as a gay man making connections, longing for psychological closeness and intimacy with other men. There’s a sense of family for me there. Does it fully represent it? No, I don’t think so, because as expansive as the exhibition at HCP will be, there are still lots of pictures that will not be displayed. I think the images in the show act as signposts and I hope the audience will want to look more deeply at my work.

LD: That’s a good way to talk about it, signposts for the rest of your work.

Your mother and father split up a long time ago. Did you ever have a chance to photograph them together? I see that you have photographed them individually surrounded by their chosen family, if you will. What has this dynamic meant for you in your life and your work? Is there a relationship to the use of the panels both in the simultaneous use of fragmentation and continuation?

DH: I was only six when they split up, so no, not really. I was very young, but there were a lot of photographs to look at of them together. It is interesting that you should mention these early years. There is one photograph that I made in college. I had my parents come into the studio for a picture when I was an undergrad at MassArt in the Polaroid class. It’s that huge Polaroid 20×24 camera, and I made a triptych. I had my parents come into the studio on two separate days and unbeknownst to them, I was piecing together the photograph of my parents having dinner together with me in the middle, as if we were actually together as a family unit. My father is to the right and my mother is to the left. When the images were pieced together, it depicted all of us having dinner together. I think it’s the photograph that got me into Yale University!

LD: I bet it is.

DH: I think that we need to speak a little bit about some of the influences, the hybridity, if you will, within my work. Although it’s photographic, it takes cues from theater and film. So, there’s performance and cinematic motion in the photos. But in the end, I’m really interested in the stillness of photography, the slowness of it. I like to stare.

When I was growing up, my father used to join pictures together with scissors and tape, a kind of poor man’s panorama. So, I grew up knowing that photography could be more expansive. As a student, I started to put images together to make individual photographs that would connect horizontally or vertically. My pictures function the way the eye works, or like a cinematic camera. The panels move with time as it changes. There’s shifting focus and elapsing time. There’s a bit of fluidity in all that stuff happening simultaneously. It is mediated through the photographic lens, so it’s storytelling, meets cinematography, meets theater, meets photography, and it all becomes a picture. There are multiple moments, little fragments of time in a continuum, but in the end, it’s distilled to one moment.

Photography allows me to bring all of these things together; it’s the purest form of my voice. It’s a very open and generous medium, though people often say it’s just the opposite. Isn’t that funny? People say photography is kind of mechanical and dumb, but it’s not at all. I feel like there’s so many other things that are frustratingly narrow compared to what photography can be. It’s as if anything is possible through the back of that camera, you know?

LD: Yes, that ground glass is enchanting, upside down and backwards, beaming with light under a dark cloth.

Shifting gears a bit, can you speak about how your relationship to family has changed over the years?

DH: Well, do you mean chosen family, or family that I cannot get away from because they are forever linked to me?

LD: I think that’s the sort of essence of the question in some way, your family being the family that you can never get away from, but then finding an ability to expand that into chosen family. I guess I’m asking you to talk about that evolution or expansiveness, or when that started to happen.

DH: Yes, for sure, many of the people in my photos have physically changed over the years. But my photographs also show how I’ve changed, how my physicality has changed, along with my relationships to other people and certain subjects. I don’t know, maybe it’s a combination of both myself and the world evolving. I think my vision, be it historically, psychologically, or photographically, is always evolving, perhaps in tandem with the subjects I’m photographing.

That’s a slippery question, right? Because you don’t know what has really changed, the subject or the maker. For me, there’s a lot of my pictures where the camera has become a buffer between me and a world that I don’t always fit into, that I don’t always understand. The camera is a way for me to kind of look at all of it, have opinions, and then make things. Back to your initial question about curating spaces: I want to make the world look the way I wish it would look, to connect with men, often strangers in a way that I wish I could connect with in real time. It’s also a way for me to look at things that I don’t like in the world. In that way, my process/work is therapeutic. It illustrates a lot of my joys, pains, woes, and confusion, stuff that you would basically talk to a therapist about.

LD: Right, and you still managed to make it humorous at times. Can you speak to that?

DH: Well, humor is a foil, isn’t it? I use humor all the time. Keep them laughing so you don’t cry. Laugh at yourself before someone else can. That I learned as a kid. I’m still like that all the time.

LD: I know. We would never notice though, because you’re so charming and smart too.

I find much of your work so tender, and there are a few images that have a great distance between you and the subject matter. Game of Go, for example, complicates the read of the show for me. How does it feel to have images like this exist in the same exhibition as portraits of your father? A lot of the work seems to be about the gaze and gazing.

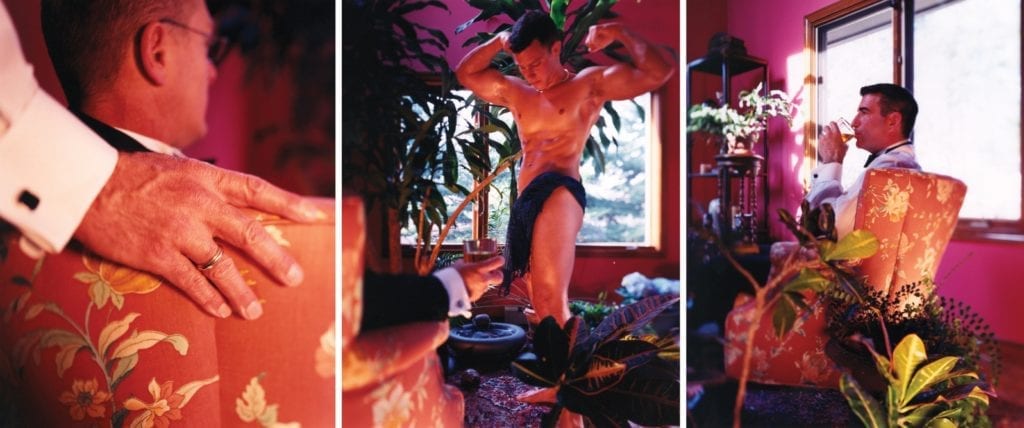

DH: Let’s step outside of the theme of this particular show for a second. I love that in one exhibition I can have images of fathers and sons—me with my father, then strangers on the street, then gay men post-coital putting on their socks. I love all those nuances of sexuality and maleness. Of course, it doesn’t have to be about men, but I’m just speaking of men right now since we’re talking about my father. I love seeing my father contextualized with other men, both strangers and friends. I like mixing it up. That’s when it gets really exciting, when it becomes like a stew of maleness. For me, it is searching for a connection, which is what we do when we search for other family. It does not always work. So maybe that’s what it is. Maybe it’s about the failure to connect completely.

This photograph, Game of Go, was a really smart choice because it is a bit of an outlier when you first look at it, this kind of empty experience. This guy’s sort of stripping, and these other guys are drinking. It’s about the haves and the have-nots, and that’s going to fail—a sad transaction between men that need something from other men.

LD: The tradition of film is dissolving, as is the image of the “traditional” family. What is your relationship to this dissolution? How are you dealing with this, both in family and in film?

The intimacy of a 4×5 camera and film, will you ever give it up and make the switch to digital? Is there something safe about being behind the big camera? Is there safety in the known reliable process? Is it like a religion?

DH: It is a very poetic kind of observation and I won’t force the metaphor, but the metaphor is there. The idea of film and traditional family—they’re both kind of nostalgic, right? Both are kind of fragile and yellowing. The American family is really changing. It’s not as easy to identify, and it has so much more potential. The nostalgic family—the mother and father and the two kids and a four-bedroom house and whatever—all of that stuff is fading. And so is analog photography. It’s all somewhat obsolete and ready to be archived. I think there’s a really interesting parallel. I enjoy the materials that I use. I love using that view camera. It’s not that I couldn’t get a digital camera. If Kodak called tomorrow and said, look, we’re not making film anymore, I would hit the ground running. I would surround myself with someone like yourself or other people to help me figure out which camera I needed. I could make my pictures look the same way, but it would not be as much fun.

LD: The ritual of the process would be missing.

DH: I love taking my camera out there. It is on some level entertaining, especially if my subjects are strangers. People like to see the camera. It is not a slick, new camera. It’s an old-time camera, and people feel like I am not the guy who’s going to steal their identity. So, I like using it. I love how it looks. I still think the view camera does a lot of things that is hard to duplicate with other cameras—the swings and tilts, the unique optics and depth of field.

I live in both worlds; I’m an analog and digital guy. And, I have seen huge shifts in technology and trends in the photographic art world. So much has come and gone. Form and content ebb and flow. It has been, and continues to be, a challenge to maintain my voice and the truths I feel about the world and my work. But I do it. Actually, I think I have a much stronger voice photographically than I do in a lot of other aspects of my life. I think it is my strong suit, and that reason alone is why I keep doing it. It never dawned on me that I wanted to do anything else.