I met Curran in a dark bar in Manhattan after a talk he gave at Higher Pictures in 2015. I was in the unsteady midst of my grad school experience. We knew of each other and our photographs. The conversation was brief, but we’ve remained in contact ever since. Two years later, we were invited to ask each other about our respective projects, road philosophies, and finding a home among strangers.

Matthew Genitempo (MG): When I think about travel, I can’t help but think about a destination even though it’s just one small aspect of traveling. So many of your photographs function as results of a larger situation made on the way to somewhere else, sometimes as if there is no destination in mind at all. Can you tell me about how you end up where you end up?

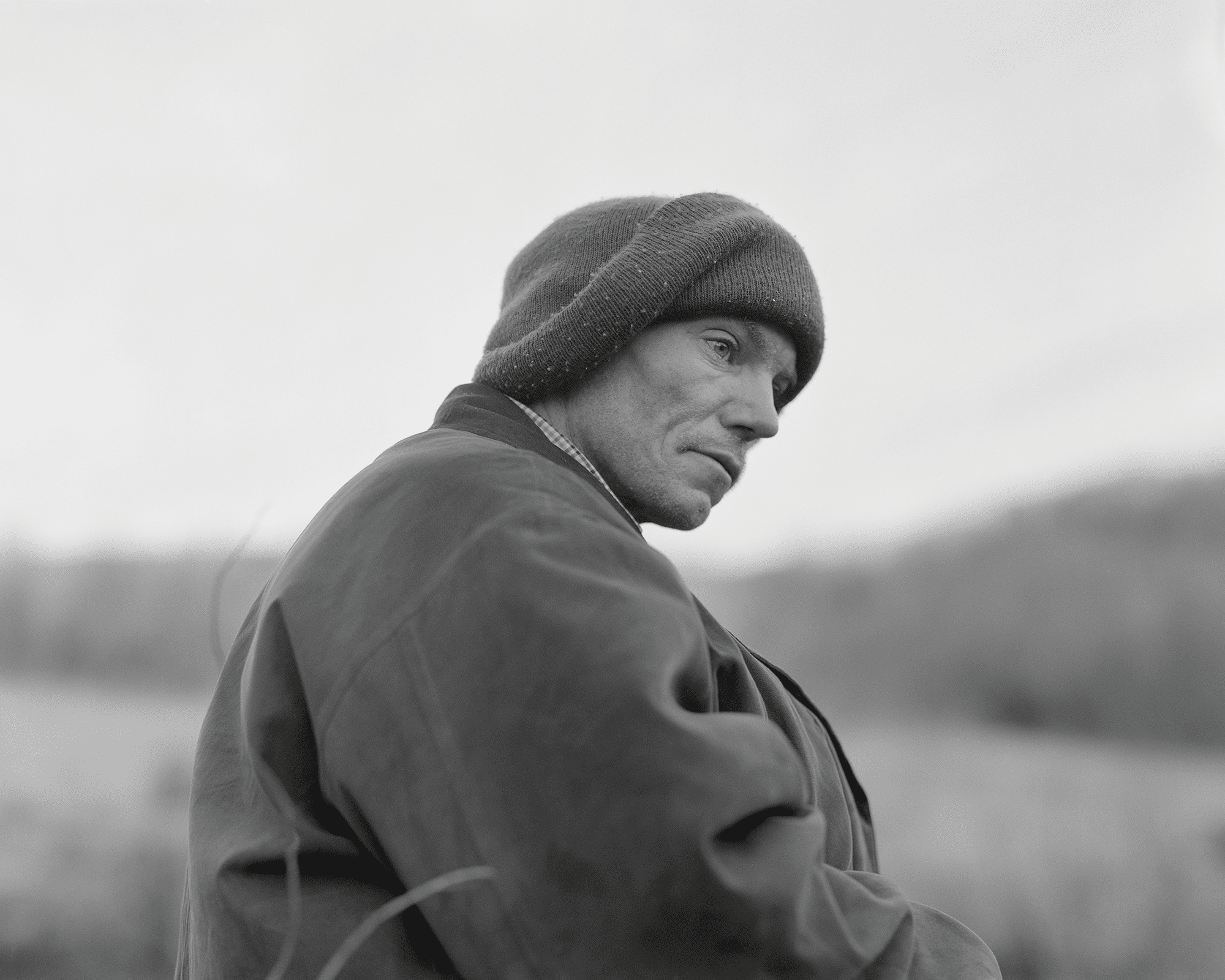

Curran Hatleberg (CH): I end up in places by chance. Chance and accident are the foundation of my entire practice. I start out with a vague notion, aiming towards a region I’m interested in, then wait until something feels right. It’s purely visceral. I like driving long distances, looking around, making it up as I go. It’s a loose approach that favors intuitive thinking over analytical design. Then, when I finally find a place, there’s no mistaking it; there’s an undeniable atmospheric weight. I can feel it come over me. A place that’s a sure thing will almost feel like a stage.

It’s not enough to find a mysterious place, though. Unless something happens soon after arriving, I’ll leave and keep looking. Ultimately, I need to find someone who will open up that world for me, who will show me the inner life of that place. Once that happens, I relinquish control to that person or group of people, and things start happening. From there, I could never guess where someone might take me, whom they might introduce me to, or what they might choose to reveal of themselves. Without that accidental encounter, nothing can begin.

MG: It’s strange. This might just be personal, but on occasion, searching usually leaves me trying to look for and construct a pre-visualized image. Most of the time that doesn’t do me any good. Do you ever find that the search is masked by a preconceived idea or possibly a photograph that you’ve imagined? And if so, does that function as a distraction or a hindrance from being able to actually recognize or appreciate what is happening in front of you?

CH: I feel like I have images in my head that I can never get out. Maybe it’s a scene from a book I’ve read and elaborated upon in my imagination; maybe it’s a vivid memory that’s gone but is still resonant. I carry these fragments around with me. I look for them uncontrollably. They hover over my subconscious so sometimes, yeah, without even trying to, I’ll set out on the impossible task of finding those images in reality, as if with enough conviction, I can compel them into existence. These pre-visualized images have a perfection that is haunting. It’s a fool’s errand though, you’re right; these images must be recognized for what they are: ideal and therefore lacking a precise analogue in reality. They simply can’t exist, or rather can’t exist the way I have hoped for.

I find in general my best pictures are made when I’m emotionally open, aware, but not overthinking—photographing things before my brain has analyzed or understood what it is I’m really seeing. Typically, it’s the visual recognition of form and light, an aesthetic convergence, not the identification of deeper conceptual meaning. I suppose that’s just gut feeling at work? Henry Wessel described this perfectly: “It’s thrilling to be outside your mind, your eyes far ahead of your thoughts.”

MG: Are you ever in a place of that unmistaken feeling you mentioned and you find that you can’t make a picture? Any specific stories if so?

CH: All the time. It’s one thing I love about the medium, actually. I can be in front of a perfect situation, where all the inexplicable, incongruent elements that make an image work are colliding in harmony, and simply strike out. I love that. It’s as if the moment is too good to contain, and I just can’t catch the ghost. I also love that these moments are gone as quickly as they come, completely irretrievable.

I remember one instance of photographic failure very clearly. A man raised in the swamps outside New Orleans took it upon himself to show me around. He gave me the royal tour of the city. We got to know each other, and one night he asked me to drive him somewhere, to a place he knew. That was all he said. When we arrived, in the darkness, he climbed over a wall with an empty sack, and when he came back, it was bulging. He was running. Two shirtless men were on his tail, yelling after him. He hurried me to start the truck, to drive him away. Scared, I obeyed. The men caught up and struck the front headlight with a pipe, shattering it to pieces. Peeling out, I almost ran them over. When we were out of sight, I asked what was in the sack. Opening the bag, I saw it was filled with lemons, a hundred yellow lemons, as if there couldn’t have been anything else inside.

I tried to photograph those damn lemons all night. I tried to photograph the man. I tried to photograph the man with the lemons. I came up short every time. I guess some experiences are pictures, some are just stories. Photography involves a lot of failing. Failure is the standard of the medium. It’s the continual, repetitive outcome until something miraculously works. I never know what the moment that works will look like or if I will recognize it when I see it. I never feel the moment coming until it’s already happening.

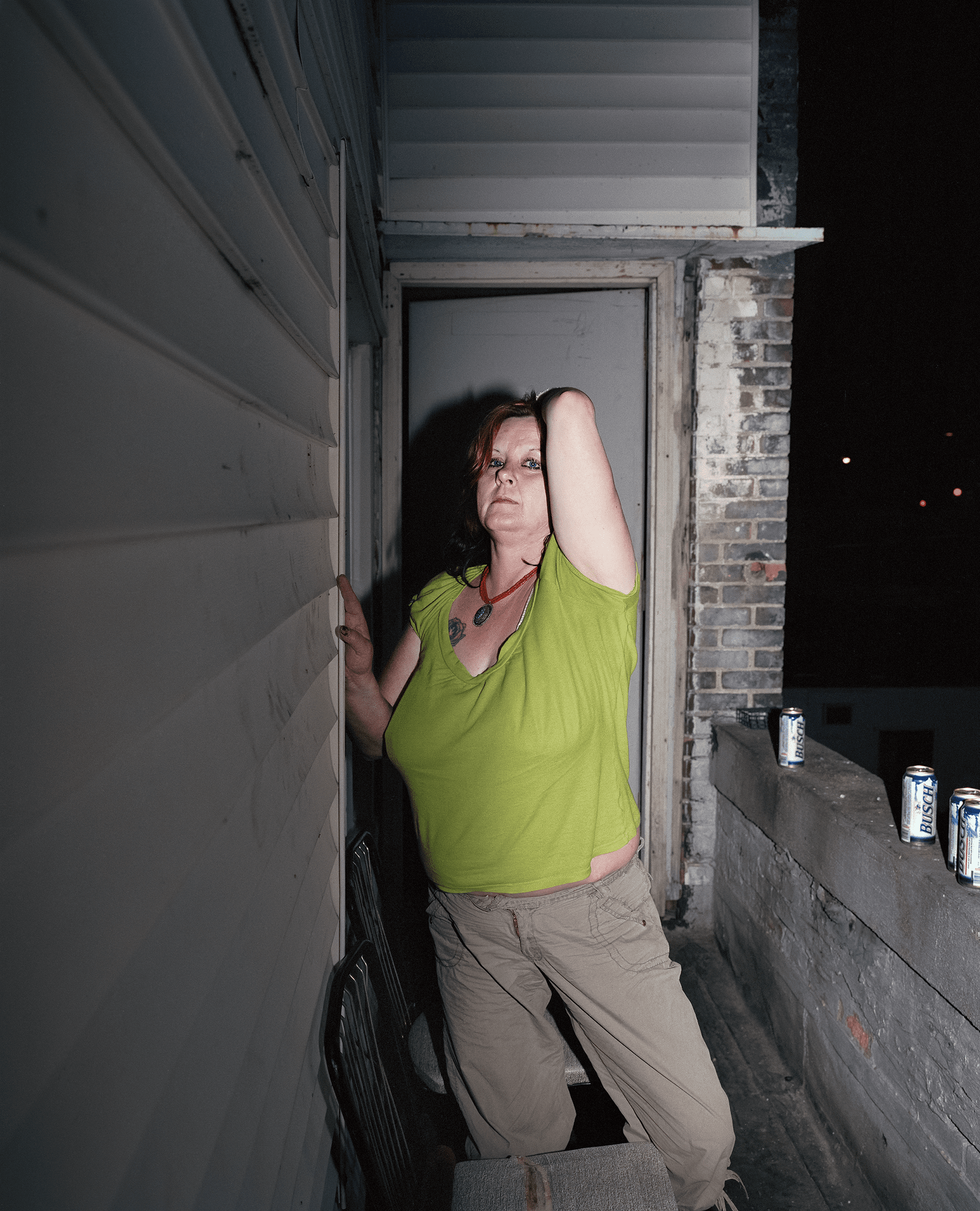

MG: Your photographs oscillate in and out of two spaces. There is the report but also a deeper respect of your subjects and the scene unfolding. Maybe it’s your inclusion into their world or the access they grant you, maybe there isn’t one defining factor, but I always appreciate the unifying sense of attention in your pictures. Mary Oliver said that attention without feeling is only a report and that attention is the beginning of devotion. I feel that you’re devoted—to the people, the place, the moment—when I look at your work. Is devotion something you think about?

CH: I feel a specific devotion to the unknown. It’s a kind of worship. When I stumble into the right person and place and feeling, I want to go all the way in and let it wash over me. In those rare moments, the world is so overwhelmingly generous; everything feels imbued with reverence and wonder. It’s like a headspace where I can achieve an eerie clarity that feels more like mystery than clearness. Does that make sense? It’s as if somehow, I am experiencing the real, the surreal, and the imagined all at once. These moments seem to validate my instinct that the deepest understanding arrives through the process of photographing, not planning. I am committed to spending time with people and in places that are unseen and unknown to me.

That being said, my greatest devotion is to human exchange. There is a natural but dangerous tendency to assume we understand people and places we do not know. But people are so complex. They have the ability to be both entirely predictable and also wildly unpredictable. All the biases, past associations, and stereotypes we naturally have shortchange the complicated reality of who a person is. The best way to override these biases is through direct experience. Photographs of people and the process of photographing them force an interest in lives other than our own. When this works, we feel ourselves reflected in someone else, removing indifference. This may sound obvious but when I spend time with someone, when I slowly begin to uncover things, real emotions, I always have this existential crisis: a realization that everyone—every person out there walking around—has a life as haunting and complex as the next. And this realization circles back, forcing a mirrored awareness of my own life and its trajectory, and maybe for a second, the plot of my own existence I felt so certain of minutes before feels foreign and doesn’t make sense anymore.

MG: Does guilt ever enter into the equation because of your ability to come and go from these places?

CH: More often I feel sadness. I always suffer a similar withdrawal after returning home following an immersive trip. I try to brace for it, but I can’t avoid it. On the road, the world is a hallucination. A metamorphosis takes place. Things are said, sights are seen, meaningful relationships are built and shared, and I open up completely. I learn things I couldn’t have prepared for. Often that time is better than I could have hoped for, better than I ever deserved, and some sense of real astonishment is attained. Actual understanding is achieved. When I’m there in the moment, I trick myself into thinking I have limitless time and opportunity, but eventually, time runs out and I embark on a separate path, and I’m alone again, left with memory and echoing conversations. Before I know it, I find myself back at home, and all the revelations and stories and faces are fading rapidly from my awareness. Did it even happen? You can’t live inside a hallucination very long. It’s cliché, but the time spent with people is a privilege and sacred and it ends fast. Too fast. Then all I’m left with is the realization that I may never sit at that person’s table again and share a meal. I may never see that particular house again, or that specific body of water, or that face or family again, and if by some chance I do, it will only amount to a very few moments across an entire lifetime, and it will be totally different the next time, because they’ve changed and I have as well. I’m not good at goodbyes.

You travel extensively for your work too. You live your life uprooted, out in the world exploring. For me, because the photograph and the experience are wholly separate entities, there is a frustrating inability to fully divulge a meaningful personal experience I have out there, to communicate what a person or moment was actually like in reality. Do you ever feel the tendency to give up trying to talk about an experience you’ve had while photographing, because the picture can only say so much or can only say something totally unrelated? Do you think a picture can ever act as a stand-in for your own experience?

MG: I have an especially difficult time talking about experiences with people who know me well because I’m more uninhibited and willing to take risks when I’m out there. It’s like that William Least Heat-Moon quote: “When you’re traveling, you are what you are right there and then. People don’t have your past to hold against you. No yesterdays on the road.” Nobody knows who I am on the road. Explaining an individual experience in the condition I’m in when traveling is nearly impossible. I’m a different person when I’m making work.

I’m not even sure why I still ask photographers, “What’s going on in this picture?” I’m usually disappointed when I get an answer. We build stories around pictures. That’s one of the fantastic virtues of photographs. Usually an explanation of the event leads to disenchantment. So, if giving up means letting the image retain its spirit, then I’m all for it.

A picture has the possibility to do so much more than describe the event it recorded. I am not sure if any of my pictures function as stand-ins. I am closer to certain pictures because I know the amount of work it took to make a photograph or what unfolded before and after I made it, but that doesn’t really matter. Once the pictures are out there, unbound to any sort of explanation I can give, the viewer can bring their own history to the work and create their own experience.

CH: I would agree that too much back-story can often kill the magic. When everything is reduced to fact, the mystery dies. The enigma disappears. Remove those answers and the world created by the photograph deepens and opens up to interpretation. Good pictures tempt us into the belief of a narrative structure, while at the same time they deliberately withhold that narrative. It’s the open-ended quality of a picture that’s so amazing – when it welcomes creative interpretation and invention from the viewer; when it invites the viewer to participate, walk around inside the photograph’s world, then take the wheel, and think up origins and outcomes that can never be confirmed or denied.

When making Lost Coast, I attempted to make pictures that communicated more what my own personal experience of that place felt like, not what the place is really like. For me, the work is more like a dream I had about a real place than a depiction of reality. There’s this incredible hubris in to trying to portray a place or a person. How can a photographer ever possibly represent a unique region, lifestyle, or person within a few pictures? Jasper is in fact a real place, a point on the map. How did you navigate its representation in pictures?

MG: Every moment is fleeting and everything is constantly reshaping. I don’t think it’s ever possible to get an objective representation of any person or place, especially through photography. The medium is fundamentally subjective. Making photos in attempt to communicate your personal experience tells me something much deeper than the descriptive accuracy of a place. A place, in this context, is much more fascinating than an on-target representation. It’s like when Richard Hugo said: “…once language exists only to convey information, it is dying.” The individual voice is what I am interested in.

When I began Jasper, I wasn’t conscious of what I was constructing. It didn’t register that I was making pictures that reflected my interior. Once I realized that I wasn’t making work about a geographical location and I was trying to pinpoint something inside, the idea of accurately representing the town of Jasper went out the window. When you give up trying to be honest to a place, you can be honest to your feelings. If Lost Coast is a dream you had about a real place, then Jasper could be considered a reflection of an inner landscape expressed through a real place. I’m not sure if they’re the same, but both approaches are cut from the same cloth.

CH: What were your relationships like with the people you photographed in Jasper? Why is it important for you to cultivate long-standing relationships when you’re making pictures?

MG: I remember hearing Susan Lipper talk about Grapevine and mentioning that she considered herself to be part of the group she was photographing. I never fully felt that in the Ozarks. I considered myself very close to a lot of the people but felt that my advantage to come and go always sort of loomed over our relationships. Maybe that’s why I asked you about guilt earlier. Maybe it is just inherent when making pictures this way, but leaving is part of it and that was something I felt we both understood. That always created a palpable distance that I could never shake.

The people I sought out don’t have many visitors and are pretty wary of strangers. There are a lot of single track dirt roads that lead to nowhere. Nobody is “just passin’ through” and folks out there aren’t shy about their firearms. I found that out the hard way a couple times. But wariness aside, they’re gracious and willing. The camera can work as a key into another world and upon entry, you can begin to build a connection.

Long-standing relationships are crucial for this type of work. These men were my guides. Even though they’re detached from a larger community, they’re all strangely connected. Each person would carry me to the next. There are people living out there who can only be found by word of mouth. Folks don’t just freely give out that information. You have to build trust. They opened their homes to me and these spaces became sanctuaries. I am indebted to them.

CH: For me, the Lost Coast region feels like the rugged edge of the world, like this place of no return. I had this persistent feeling living there that I could just disappear and no one would ever know or find out. I suspect this idea had a lot to do with the undeniable mystery and grandeur of the nature there. Nature looms large in Jasper. The distinctive landscape of the Ozarks is a major character. How does nature play a role in the narrative? How does the landscape affect the people who inhabit that place?

MG: Making photos in the Ozarks was the first time I had ever made pictures in a place with dense forests. I’ve been making pictures in the West for the last decade where I could see the horizon, but out there, you get swallowed by everything. It’s relentless. On the road, I spend most nights in the camper attached to the bed of my truck and sleeping was never a problem until I started making pictures in the Ozarks. I guess my point is that nature is unavoidable out there and that undeniable mystery was constantly pressed against me. The people are affected by nature because it’s inevitable. You can’t silence it. The people out there have to live with nature, not just in it. There’s no compromise.

For me, nature doesn’t play one solitary role in Jasper. Some of the landscapes function as an impossibility, as completely untouched land, a representation of the spirit of what nature was, while others sing the harsh reality of our selfish utilization of the land. And just as unmarked land isn’t attainable these days, so is a complete disconnection from society. In that way, the portraits and landscapes share an impossibility.

CH: Now that Jasper is completed, what’s on the horizon?

MG: When I made Jasper, I contended with my fascination about running away and I’m not sure if I’ve gotten all of the work surrounding those interests out of my system. I’ve officially moved to Marfa, where it’s much slower and quieter than Austin. It feels like an escape, so that helps. I don’t plan on making pictures here, but using it as a base to come home to after being out on the road. It’s been a long time since I’ve made pictures out West. My feelings toward this area are still strong as ever. I am not entirely sure what’s on the horizon but my heart is here.