Right now, Hadi’s works are large, later he’ll say they’re nearly the size of a person–his person or a person like him. When I first met Hadi a few years ago, he was working through a hyper-layered chance-based darkroom technique, a repositioning of the photograph in color at a scale relational to a human or a rug used for prayer. He was titling his work after jokes that follow the cadence familiar to Americans in the form of “Yo Momma” jokes. Yo Momma so stupid; Yo Momma so big; Yo Momma so poor; Yo Momma so… instead of this Dozens play, Hadi was framing around Hadji (spelling similarity coincidental and intended). What Hadi was doing with Hadji–or what I think Hadi was doing with Hadji–was using him as a way to speak to the multiplicity of the racial concept of Hadji, so that his photographs might occupy the funny space of the othered self. Alone in the darkroom, Hadi, plays Hadji to make a photograph.

Now, he has left Hadji behind, his newest body of work, aggregated together as The Truth has Four Legs, utilizes the same large scale, collapsed, looping, gestural, premeditated photographs (photograms, performances etc. ) to pose questions about looking, knowing, memory and perception. If my descriptions ring with the tonal bells of discord, then we are on the right track. Hadi says and shows in There’s Been a Mistake what appears to be an Arnold Schwarzenegger shooting a mirrored Arnold Schwarzenegger in a high sepia blue dessert. Overlaid on the Schwarzeneggers in a light-purple-meets-light-cyan photogram, Hadi’s legs (or their shadows) stand in invisible, gesturally drawn shackles. In the background, a new (read shit) mustang looks lazily, proverbial eyes glazed over. Where is the mistake, Hadi? Ah the chains!

Hadi stays funny and serious like your one dry piece of clothing in a rainstorm after failing a test: does my undershirt get an A+ from the universe? He makes this zigzag of feeling again on the jug of a man bent and bowed, while he draws above that odd somehow contemporarily classical form a simple two eyed devil with an easy circle mouth and even easier horns. He leaves the mouth perfectly positioned around the head, with the mouth becoming the head and the head becoming the mouth back and forth forever. He calls this casual summersault Hidden in Translation.

Here we speak about his process, his recent photographs and keeping his ideas close and somehow fictitious to go off very far and truthful.

Rindon Johnson: Can you tell me more about your process? How are your photographs made?

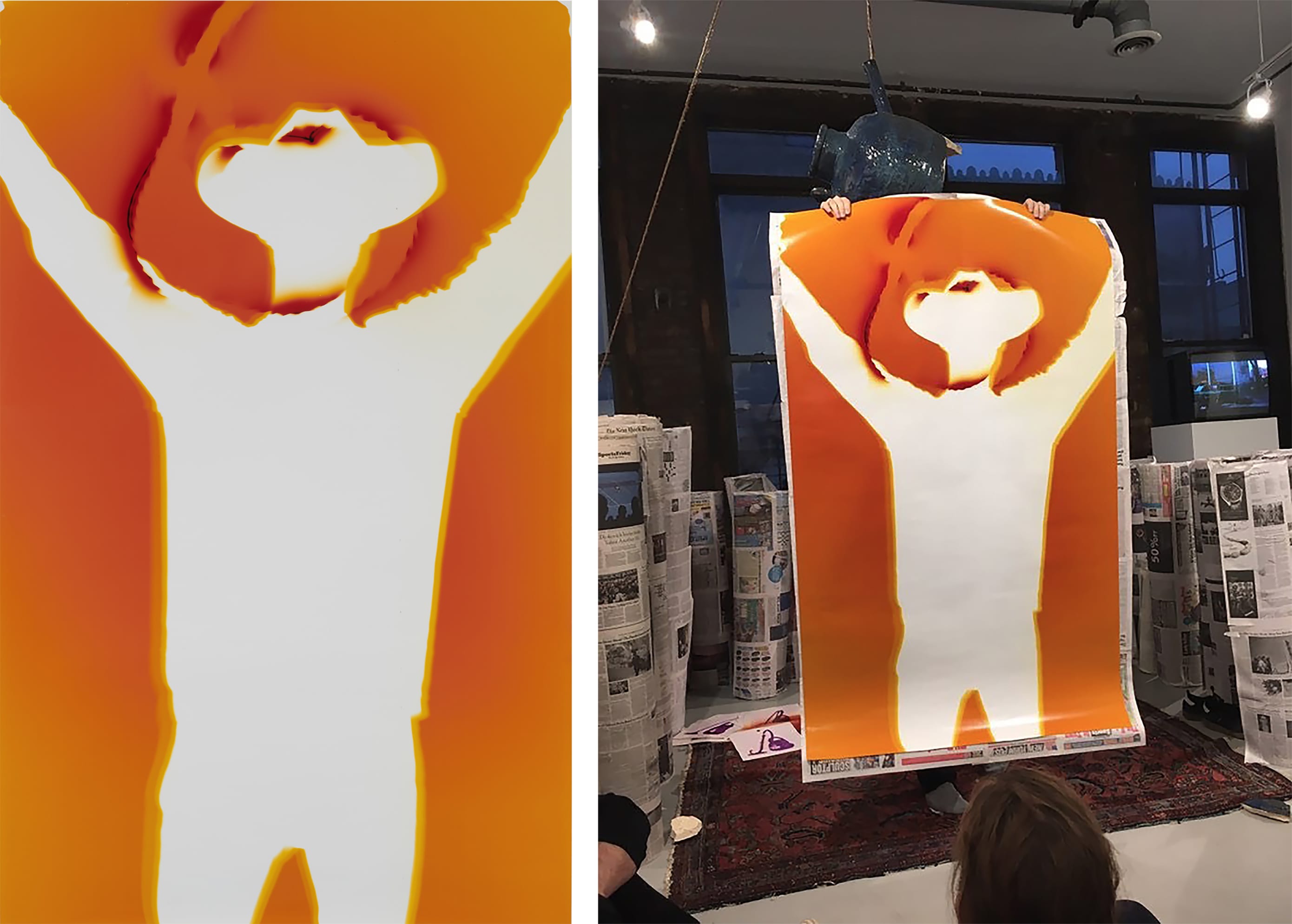

Hadi Fallahpisheh: My photographs are made completely in the dark, in a large darkroom space I have constructed specifically for these large-scale prints. I work using my body, enlarged found images, and a variety of drawing techniques made with flashlights; the results often incorporate photograms of my limbs or entire torso along with marks and drawings that I have made. The photographs are made within a process of color darkroom photography that results in a final, unique chromogenic print (or c-print) that is not digitally produced. To clarify, for example, the image of the pot, Hidden in Translation, was made by exposing a negative of the ceramic vessel onto a large photographic paper. My body, which you can see the outline of inside the pot, acted as a photogram blocking the light from reaching the paper and thus, blocking the image of the pot from the area my body took up. The drawing aspect of the work was made with a red flashlight resulting in the blue marks that make up the horns and eyes at the top of the pot. Or in the work, Punishment II, you can see that I have enlarged an image of two gloves and have laid my hands on top of the paper causing a photogram of my hands. On the right and left side, I have made two outlines of my hands using flashlights.

RJ: How does color play a role in this work?

HF: Color arrived through my own thinking. When you walk in a pitch-black night and a car is approaching you, and instead of just bright white light, there are the blue and red lights of a police car flashing, then you know something is not normal. I wanted to bring that feeling of the immigrant experience into the work. When I am in the darkroom, that is my studio, and I can see nothing; it is even more pitch black than the darkness of night. Everything is shifted by a single colored flashlight. If it is red then everything, even my body, is red; it’s the only available light. There is also a technical fact within the medium that I am conceptually interested in. Every color that appears in the photographs is inverted, meaning if I use a blue light to expose the image onto paper, the photograph will end up appearing yellow. The same goes with my flash lights that I used to draw, write, or make marks with. I have made a set of different flashlights with different colors. I am conceptually interested in this inversion that speaks to the differences between what the speaker wants to say and what the receiver is able to hear.

RJ: How do you feel about chance and it’s permeation through your work?

HF: In the medium of photography, one has all these tools (shutter speed, iso, aperture, etc.) to control the light in order to make a perfect exposure, in a larger, constant attempt to create the perfect photograph. I am interested in undermining this control that happens so instantly when one starts to work with photography; that is how chance has come to play such an important role in my work. From one angle chance is part of photographic apparatus dictating the fact that no two photographs can ever be the same and, yet, I am conceptually interested in the idea that when you let chance come in, the will to make the work perfect will leave you alone. What chance does in this process is making every photograph a unique object that will be impossible to remake; I try to take that to an extreme. The process of making these works for me is another kind of performance: being in a dark space, having a fixed time frame, and a certain amount of moves and tools to perform with.

RJ: That is a necessary reminder: chance lets you leave perfection alone. Chance’s friend, Improvisation, seems relevant to introduce then too, especially with thinking about your performance, The Truth has Four Legs, at Simone Subal Gallery. Can you tell me more about the performance? What happens? How are the photographs used?

HF: The idea of performance was in one way a path to agitate the functionality of my photographs. When I was making these photographs, (they are made within the seven months of my life where I lived in a rural part of upstate New York) they were directly coming out of my daily life experience and what I was reading in the newspaper. I was taking upon the role of an amateur journalist, who has no camera and in turn, makes his life into a camera obscura. But then I was aware that photographs–in order to be used in a journalistic way–need captions. Instead of doing the obvious by putting the narrative text into the photographs themselves, I came up with an idea to transform the text-caption of every photograph into an audio form. My idea was that it would be interesting to make documentary photographs without a camera, and to find a way to have the captions exist in audio form, without them ever being written down. I also wanted to bring to these silent works something that would make them literally loud, and that ended up being my own voice.

By transforming the photographs into a performance, I try to weave the personal and public, asking larger questions about representation, the power of the photographic image, and the subjective nature of the past.

RJ: I see those questions swirling around, like how does one perform an image? You dance around answers agility in a lot of your work. In that same show at Simone Subal Gallery you have a piece with haunting, kind of terrifying sounds coming out of a beautiful blue jug hanging precariously over a worn rug, how does that piece tie in to your performance and the photographs?

HF: I made the large ceramic vessel myself and for me in my studio it began to exist as a reminder of a site where one could possibly hide or get stuck within. It became a piece later with the addition of the audio. The sound component, which is housed inside the pot, conjures a sheep who is trapped or hidden within the pot and is calling out for help. I wanted something that would address the viewer directly and would reference this feeling of containment. The text for the audio comes from three or four different languages, but all in all the viewer wouldn’t necessarily approach the pot for its shape or beauty but more to try to understand what is that sound inside.

Also, the carpet beneath the pot has been used over the last two years in my studio for studio visits and acts as the stage for my performance.

RJ: To editorialize, I feel like this sheep (or the idea of a sheep) is really important to the performance and I feel like his voice echoes in my ears when I think about you rolling and unrolling your photographs (images, drawings, artifacts, coming togethers). The “bahhh” seems to be functioning on lots of levels. Somehow when I heard it, I was thinking about the first time I saw the square pupils of a sheep and how suddenly the “bah” felt other worldly and alien. The sheep felt from elsewhere, despite the fact that I was probably wearing a wool sweater…

HF: I was using this “baahh” also as a tool to agitate and twist my accent in the performance. What I mean is the idea of me with an Iranian accent performing and telling/reporting a story in English might be complicated on its own, but then when I try to also impersonate and replicate a sheep’s sound, it becomes and interesting moment for language and text in audio form. There is no written text, and it is always the images that remind me of their own captions. Every time I perform it, there are little changes that come up. In this way, the performance becomes a kind of report that is always about the same thing but is never actually the same.

The rolling and unrolling of everything and telling the information assigned to the photographs might remind some people of a rug seller. It is also a strange display system and against how one should traditionally treat photographs.

RJ: In the performance, you struggle just enough with the unrolling of the images. Can you tell me about the scale of these photographs?

HF: Most of the images are enlarged to human scale, and the photo paper is big enough that a body can fit on them or hide behind them.

RJ: How does the newspaper backing on the photographs situate the work?

HF: The newspapers are supporting the photographs–like a protective backing for when I roll them every time–and also, every newspaper is from the same day I made the photographs. Each work is carrying the date they are made and all of the events that happened on that date to make the headlines. These headlines operate as a mundane and almost trashy backdrop to the work; next to the cowboy print could be the headline for Trump’s latest travel ban. These kind of daily events were happening while I was living in an extremely conservative neighborhood in rural upstate New York.

RJ: This is a big and funny question, but what do you think of photography as a medium? What draws you to it, and what keeps you coming back?

HF: I mainly focus on the limits and promise of photography today–a tool for social discourse, marker of memory, and arbitrator of meaning. What personal, social, historical, and political associations do we bring to what we see every day? What is the gap between personal and public perception–between picturing my own self and being photographed? I believe these questions that I try to bring up within my work are at the same time critical and deeply personal. I try to take the familiar to a strange place in order to be able to tell stories of displacement and opening a space to transform the ways in which we see photographs, history, the current moment, and ourselves.