“My final prayer:

O my body, make of me always a man who questions!”

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

Iranian-born and New York-based artist, Arash Fewzee, offers a unique practice through which experimentations on photography unearth urgent questions regarding the medium, it’s history, invisible labor, and the structures surrounding our systems of value.

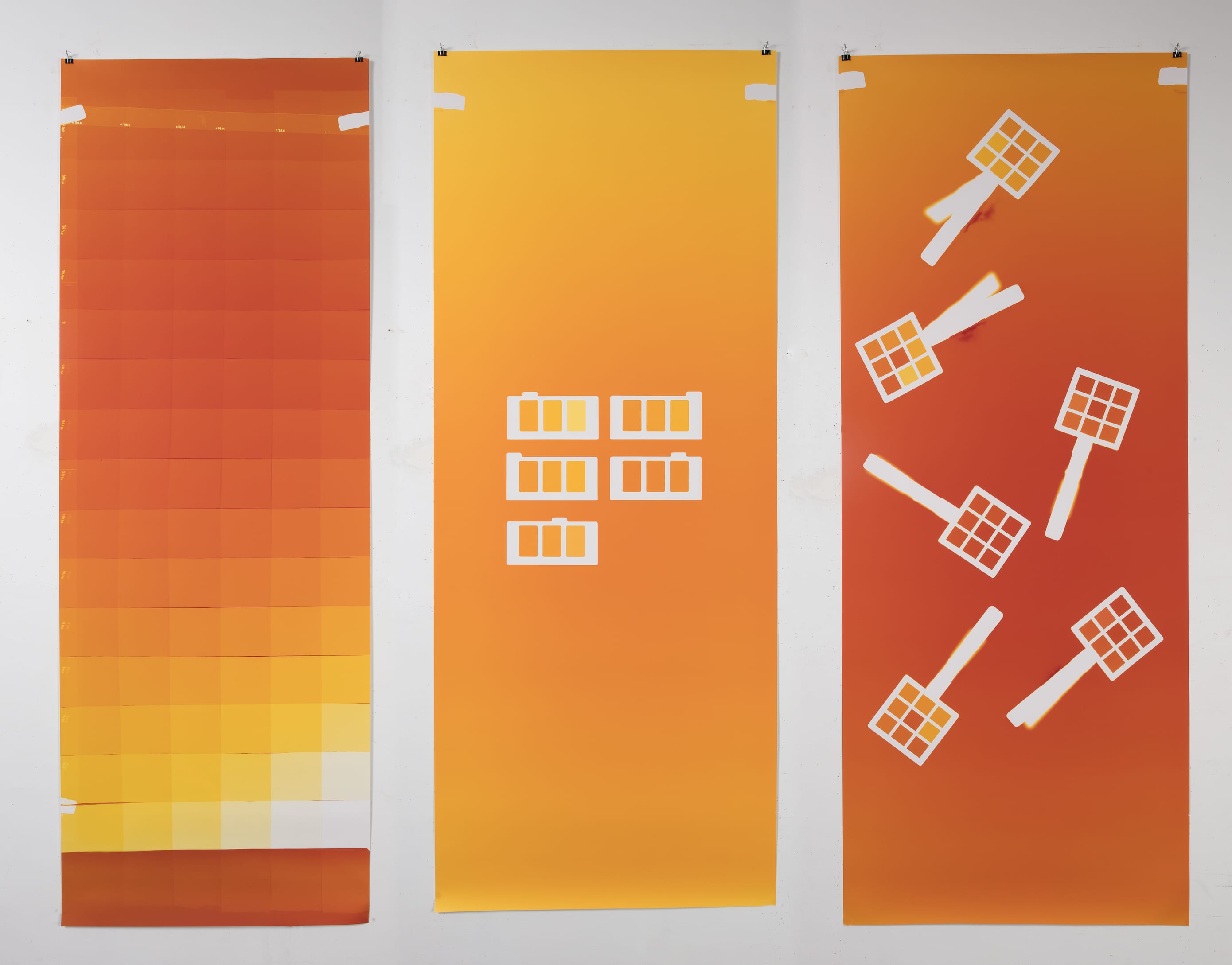

Three hanging long scrolls of paper gradually curve off the wall; each a colorful and seductive darkroom print, simple explorations of a bright shade of orange. The first is a beautiful and meticulous grid of variations of the color, from a small square of a dark muddy orange to a blown-out white. With a closer look one finds interruptions to the perfect grid, two mysterious blown-out rectangles are found on each top corner and on the sides of the columns are scribbles of numbers and words. The other two prints too are odes to this color. In them, one finds placed on top of the backdrop of the orange a number of identical objects that holds gridded variations of the color. The detail is increased from the second print to the third. Fewzee gradually moves towards the perfect variation of the orange.

Behind their visual allure and the nearly Minimalist approach, Fewzee’s triptych is filled with signifiers for those who are fluent in the discourse of photography, or perhaps more importantly, those who share the memory of working in a color darkroom. The first print is recognized as an obsessive take on the “Test Strips” and the scribbles the artist’s technical notes. The silhouetted objects in the second and third print unravel to be filters used for color-correcting. The piece becomes a dedicated take on the first lessons of darkroom printing, the test-print. For Fewzee, this old trope—designed to be invisible and ultimately disposed—becomes the final product. In this work, the old rules and system become a field within which Fewzee plays, with pleasure. Then one begins to recognize the mysterious rectangular interruptions on top, which repeat on all three pieces, as the footprint of A-clamps, tools commonly used to fix and flatten rolled paper. It is in this realization that the mystery of the desired color is solved. It mimics the iconic orange of the hands of the A-clamps—that also signifies many other tools found in both art workshops and construction sites. The piece is accordingly titled “If One Says the Orange of A Clamp” (2016). One gradually realizes that the masterful photograms are a playful remembrance for the long hours spent in the darkroom as much as they are subtle takes unearthing the disguised labor surrounding the production of art. Photography points back to itself with a deeply critical look.

This is an early piece by Arash Fewzee. Over the years, his approach to the medium has continuously gained complexity. Now, what begins in the darkroom changes and shifts meaning as Fewzee carefully moves, alters, and combines the pieces for each presentation and exhibition. Questions central to his early work now become stages to not only challenge the history of the medium but also to encapsulate our surrounding structures of power, and even subtly point to the personal effect of the current political climate.

Seven Prints and One Performance (2018) was an exhibition culminating Fewzee’s residency at the prestigious Baxter st, Camera Club of New York. For this project, Fewzee methodically explored the long history of the venue, as a space with a signature role in the history of photography. The history is a subject often explored, discussed, glorified, taught, romanticized, and yet rarely scrutinized. But rather than a didactic reiteration, Fewzee’s exhibition consisted of seven abstract “prints”—five darkroom prints and two works of ceramics, an invisible performance, and no wall-texts. The exhibition refused to be a report. Instead Fewzee brought in his research and its findings by presenting the pieces that were created, shaped, formed, and changed through the process. Once again, the prints were filled with nuanced hints for those comfortable with the medium. The exhibition opened with a large and heavily yellow print. The background was a blurry photograph of the studio. On top, one found a silk-screen print of an iconic image, which appeared illustrate a stair without a beginning or an end. The image was a seductive reference to the drawing by Picabia’s Here, This is Stieglitz, Here (1915). It is Fewzee’s homage to a beautiful historic moment, when two significant modern artists formed a friendship in the troubled years of early twentieth century. The iconic Dadaist painter, Picabia, became involved with New York’s Camera Club through this friendship. Picabia used his medium of drawing to create a playful take on Steiglitz’s beloved device, the camera. Fewzee returned to this moment and the odd depiction of the medium to offer the viewers a refuge where photography can be explored with the critical openness and excitement of its early days.

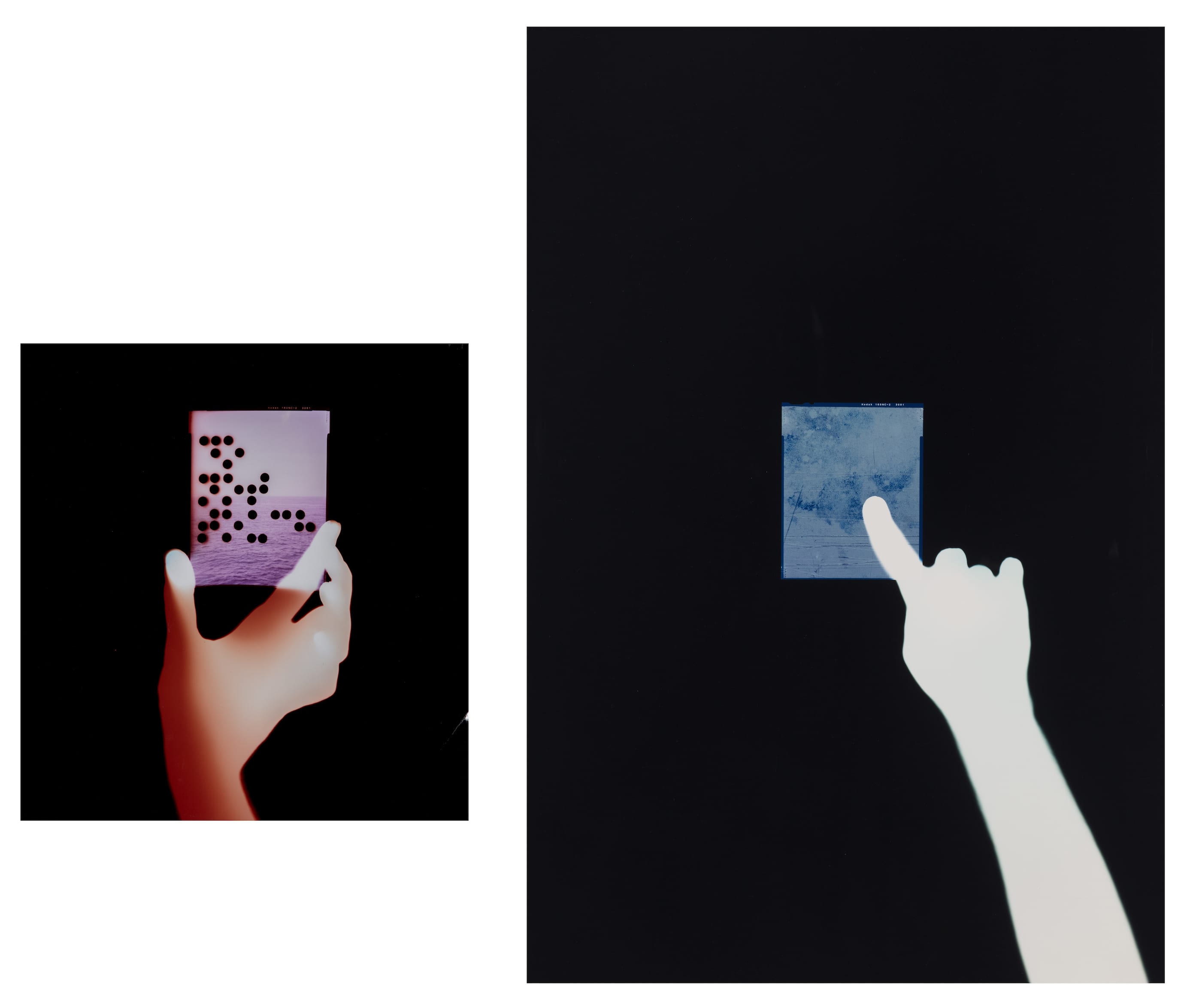

The centerpiece of the exhibition are two magnifying glossy prints mirroring each other. Each is dominantly a large, reflective black surface where one finds in a corner an eight by ten contact sheet of 35mm negatives. Here, another familiar dismissed darkroom technique, the contact sheet, takes the central role. The dozens of tiny photographs show tourists pointing their cameras at the iconic building of the New York Public Library (NYPL). Fewzee focuses on NYPL, the site in which he conducted his research, but rather than placing himself at the center, he focuses on his discoveries during his unproductive hours—the breaks roaming around the building—witnessing his medium being shared with the passing tourists. Thus “Fine Art” photography and “Amateur” photography collide and become one, momentarily. Fewzee marvels at the hierarchical systems of value within the medium. In their final stage and as the prints enter the gallery, the black glossy surface that encapsulates the contact sheet becomes a black mirror, reflecting and boxing in the white cube of the gallery. Fewzee’s take on its history, the exhibition, and its viewers. They become a contemplation on parallels of the site of the two major institutions—The Camera Club of New York and NYPL—and the similarity of the bodies briefly moving through them—Fewzee as the resident of the first and the tourists as visitors of the second. Ultimately, it is on the viewers to echo his questions and examine the structures that construct systems of value in art and photography.

Fewzee’s Untitled (2018-2019) exhibition at Rubber Factory came only a few months later, a beautiful, personal anomaly for his practice. A large wood panel sat the center of the small gallery. On this surface, one was presented with large prints that may at first glance seem far more representational than the artist’s past work. At the center is a large-scale photograph depicting a tight crop of a green field of grass. On its axis, the field has been violated and marked by a white line, distinct prints of a car-tire. In much of the rest, one finds different darkroom experimentations on one single photograph. It shows a corner of a room—or perhaps the artist’s studio—where two long stripes of wood lean on the wall. Above each piece of wood is a roll of black tape. They mimic two bodies standing by each other. In one C-print to the next, Fewzee returns to this image and with his geometric patterns, forms, and silhouettes of objects found in the darkroom, he has it challenged, interrupted, altered, explored, or perhaps simply understood. A small print shows two hands stretched out on grass. It is a deeply pleasurable scene; the photograph conveys a tactile and familiar experience, the touch of grass on one’s skin. In this rare moment, Fewzee’s photograph seem to point to not itself or the process, but a memory. One begins to reconstruct a narrative. The collection of the prints recalls the studio the artist occupied one summer in a green field. From the two objects, the corner of the studio, the field, the hands, to even the simple mark of the tires, all become a new iteration of the artist’s beloved practice of mark-making. But, what was often explored in the color darkroom is now echoed in the surrounding world, signs of life, and the remembrance of moments shared with other bodies. When the exhibition opened in the midst of New York’s cold winter, the small gallery became the studio. For the duration of the exhibition, Fewzee committed himself to keep this combination of works on the move, in flux, and active. At every visit, the viewer would enter a new iteration. But Fewzee’s body was eliminated from the room. No new print would be generated in this space. The finitude of the pieces fixed them to be only signifiers, pointing to the moment of creation when all that surrounded Fewzee—from the random objects, the studio, to the friends and community, to even the corner itself—would become material for his work. Finally, one would find an envelope discreetly poking out of a corner of a print. One couldn’t help but wonder, was the envelope a container for the artist’s secret message that had reached its final destination? Or, was the envelope empty waiting to be filled and sent off from this point of departure?

In preparation of this piece, I met Arash in the backyard of a bar in Brooklyn. After the cold, bitter winter, we sip on our beers and enjoyed a moment of spring. We chatted around subjects commonly shared among the Iranian community at this moment. Our past: old memories, family rituals, and the beloved bakeries of Tehran. And, today’s anxieties: the travel bans and what it means to be confined in a country rejecting you; artist visas and sleepless nights on alert, ready to pack up one’s whole life to leave for yet another unknown destination. When it comes to his practice, Fewzee is a man of a few words. Instead, he focuses on his life as an artist; the hours spent in his secret refuge in the New York Public Library and the deep appreciation for his art community. When I press him to discuss his work, he simply gives me his charming smile and asks if I have ever listened to Anne Carson’s Lecture on Corners.

Carson stands in Fewzee’s beloved library to deliver a speech where memories of her father’s late stage dementia is met with questions as old as pre-platonic theatre to contemporary questions of belonging and the global sense of exile. She reads in her distinct quiet tone, “Corners are what make a grid different than a line, a plaid shirt different than a striped one, a soccer pitch different than a field, an elbow different than an arm, light as a wave different than light as a particle. Corners make personality out of persons, maps out of surveillance, and a healthy brain into a demented one.” In these words, filled with so much care, I find Fewzee, his practice, and his dedication to all that is disregarded: be it performance, labor, community, or our surrounding structures of power. In his stubbornly experimental and yet sophisticatedly critical flirtation with photography, I find him gifting us a corner.