Photographer, Leonard Suryajaya and I have not met before, but have many friends in common, including Farah Al Qasimi, who will be exhibiting at Houston Center for Photography this November and who attended the Skowhegan residency with Leonard in 2017. This summer, I talked with Leonard about his time at Skowhegan, his upbringing, and his art practice.

Matthew Leifheit: One of the images of yours that I often think about is one that I believe is from your time at Skowhegan. To describe the photograph, there is a large group of people a pastoral like setting. Lakeside Offering is what it is called. Can you tell me about that picture?

Leonard Suryajaya: The people portrayed in the image are the people that spent the summer with me in Skowhegan. The figure in the middle with the lobster is Sarah Workneh, who is the head of the artist residency; the boss. I was thinking about the kind of work that I can do with the members of this specific community, while also highlighting Sarah—a gesture of gratefulness for everything that she had done for us. The image portrays Sarah as a lake protector of sorts, the lady that makes sure everybody is fed. She has a first aid kit for everyone. Everybody is there surrounding her.

I see this image as a signifier of the importance of community, but also something that is ambiguous in meaning, something unknown. Looking at the picture, it is unclear if Sarah is about to be sacrificed or if she is being praised or worshiped. I love that kind of equivocal gesture, pushing and pulling the viewers’ understanding of what I am trying to portray. I want the work to be viewed as an experience similar to that of immigration. Moving to a new place, there is something very familiar yet something very strange at the same time, something very challenging yet curious. I try to use humor while also acting as a facilitator in addition to being the photographer.

ML: A facilitator of this kind of community experience?

LS: Exactly. I also still use film cameras, which I think really helps. Because after the photo is taken, no one can ask to immediately see the photo. So instead, it’s more like, “We did it. We did it together. Now, we will just wait to see if it happens or not. If it comes out, that is great. If not, we will still have this moment to share together.”

And that is a common way my photo sessions take place. But conceptually speaking, I am making a body of work titled, False Idol, while simultaneously trying to remain in the country. The time in which I need to transition from my student visa to permanent resident status through marriage to my partner is when I will produce and make this work.

ML: You graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015, and since then you have been…

LS: Since then, I’ve been attending residencies. I was teaching for almost two years after I graduated and got married to my partner in 2016. My partner works in Oregon. He is based here in Chicago but spends half a year there, and I go with him sometimes.

ML: So, this work has been made between 2015 and now?

LS: No. The seed of it started around the 2016 presidential election, more specifically, the time of the Women’s March. I was seeing how there was so much opposition within the US, but everybody was trying to maintain their place. And I feel like that element of harmony and chaos really speaks to me in my work and in my aesthetic.

I want this body of work to specifically speak to my own experience immigrating to the country as a visual artist through same sex marriage, which typically takes about four to five years; however, within the current climate, it has been taking longer. Currently, the only thing I know about my status is that they are processing my application and I am expected to hear back within fourteen to nineteen months. I do; however, feel as though the intimate day-to-day of waiting and living as not only an immigrant but also as a husband is missing in the work. That is where my focus is right now in my studio.

ML: One thing I like about your work is that issues of queer intimacy and sexuality are not separate from the seemingly graver matters. It is a world that does not deny desire even in conversations of diplomacy, family, or even gun violence. The scope of your interests is broad but they are all coming from you. Can you tell me about the image called Arisan?

LS: The people featured include my mom, sister, aunts and cousins, and also students from the school in my hometown. So, it is a family gathering of sorts. This photo was taken at my parent’s apartment lobby during the Chinese New Year. There, they installed an elaborate hanging garden. At first, I thought, “Wow, that looks amazing. I just wonder what would happen below it in a photograph.” The costumes that the women are wearing are traditional Indonesian clothing. Indonesia has a lot of different cultures in it, and each culture has their own way of expressing their identity. So, for me, it was really important to show that within Indonesia itself, there are so many varieties of culture. But also, the way that each culture thinks of masculinity or femininity is very different. And to me, the photograph just made sense at the time. This image was taken right around the Women’s March in 2017.

My process is usually, “Oh, this thing is happening in the world that I can’t stop thinking about.” The more I think about that one thing, the more I think of the many possibilities to respond through my work. I question how to match these impulses together with what is available around me; a method of problem solving.

ML: As a photographer, you have to either make something appear before the camera or put the camera in front of something. I feel like because your work deals with these issues of place and immigration and selfhood within society, it is like everything and anywhere can be your studio. It is an itinerant studio practice that almost reminds me of the Irving Penn photos where he sets up a giant studio out of old dirty canvas and puts the mud men of New Guinea, or the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, or whoever. And of course, that work has a relationship to ethnographic photography. There is a way that I could read your use of textiles alone as actively resisting certain parts of the history of this kind of photographic practice. Because you insist on so much chaos, the mass of information perhaps becomes a language that you can carry across different images.

Do you think you’re a studio photographer?

LS: I would feel more comfortable saying that I am not, although my practice is very studio heavy in terms of the equipment and the materials that I use. Sometimes I think of myself as a director of a play. Sometimes I am a set designer. Sometimes I am the manager, managing all of these people. Sometimes I have the least amount of power, especially if it’s my family and they know how to abuse me—they do not want to just do what I say. I think of the camera as a witness of the experience that I share with the subjects in the time and space that I am in.

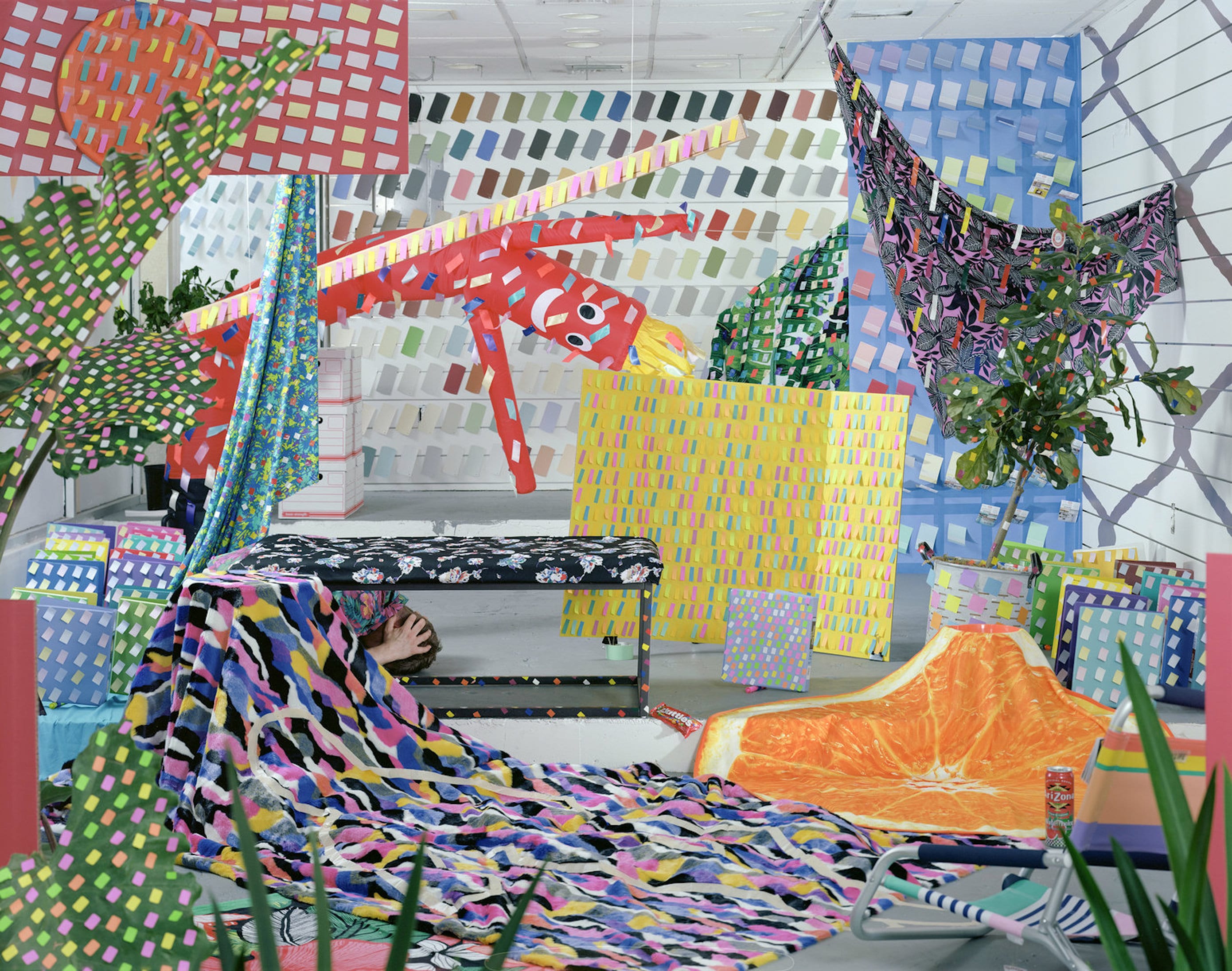

ML: Tell me about the images called Welcome Room and Pulse.

LS: Welcome Room and Pulse were taken when I first went to Florida last year. It was a few months after the Parkland shooting had happened. So, I drove from Chicago to Miami. It was also my first time driving to the South. Previously, my experience with Florida had just been through the news. I found it very bizarre how the place can be so warm, so bright, and so saturated, especially with all of the mess that happens there.

Welcome Room is an installation and Pulse it is… I mean, Pulse is Nick. I met him in Miami, and we became lovers and friends. To me, as a way to show resilience and perseverance—specifically in terms of what had happened with Pulse, is just to show somebody feeling his pulse in all of his glory.

Welcome Room is a photograph of the installation that Nick is in. There is a faint outline of Trayvon’s body on a piece of fabric; the Skittles and the Arizona Tea are also included as a nod to the tragedy, but also… I mean, that needs to be remembered. My experience in Florida is so heavily affected by the incident to a point, but at the same time, this work is not about Trayvon. It’s more of a collective coming together of color, loudness, and the red human figure. I want to refine these nuances and host them together in one image without giving too much weight to just one aspect of it.

As much as it is about tragedy, it is also about celebration. When the line becomes blurred, I feel I get to really be in the middle and think about these two polar differences. Just being in that middle space. I would not be able to fully celebrate just as I would not be able to fully cry. So, I’ll just think about it.

I first moved to America when I turned eighteen for my undergraduate degree. I spent seven years in California before I moved to Chicago for graduate school. And I remember my first experience moving to America was very confusing. I did not have any existing context around slavery. However, when I moved to America, I could see the repercussions of that in the culture. I also did not know anything about Stonewall. Really, I also did not know anything about how gay rights or women’s rights came about. So, when I first came to America, it was just very overwhelming. And I wasn’t sure how I would fully fit in. For two years, I spent my time talking back to an audio recording just making sure my English sounded like a general American English.

I did it because I had the determination and I had the drive. But it wasn’t until the 2016 election, and the context of what is happening today, that I started looking back. And I question why I felt like I was not enough. Or why I felt like I had to do all of these things to feel welcome. With that in mind, and also with a new understanding of the processes behind same sex marriage and the same sex green card application, all of these layers just start to bubble up. I feel like now is the time explore it.

ML: It seems like the studio for you, or whatever place you make your studio, is kind of a collecting place. It is a container of sorts. And maybe what I am referring to is not so much a studio or a space, but just the camera frame. It seems like you are trying to fit as many significant details and conflicting views into the same frame as possible.

Do you feel that there is an active translation that happens here? Are you translating between one place and another?

LS: I think so. Because in thinking of my work—in terms of choosing specific patterns or specific objects to go in the frame—include signifiers of the time and place of the event that I want to show. So, when I was in Indonesia, I made sure to include traditional Indonesian patterns as well as Chinese patterns. But in the Florida setting, I make sure there is an orange, which is specific to Florida but also recognizable everywhere. I include recognizable visual stimulus, and make sure that those specific cultural specifiers are also juxtaposed with materials that are transverse and can be found anywhere, not just in Asia or America.

For an example, with Welcome Room, I saw that orange carpet and knew it needed to be in the photograph. It needed to have a red human figure. And then came the rest of it—the Post-its, paint swatches, and school materials (I went to Florida directly after the Parkland shooting as well). All of these items were fresh in my head. For me, those school materials are more transverse compared to the orange carpet. I felt that they both needed to be in the same frame to not only exemplify the complexity of what I was experiencing, but also the complexity of the place. How can a place can be so inviting but also so scary?

ML: I guess when I have seen your previous work from afar and from the small amount of interviews that I have read, the way that you talk about your work struck me as very autobiographical, or very much based on identity. I feel like this new body of work seems like you are trying to mix that kind of approach with an increasing amount of culturally shared, or as you said, more transverse subjects. Translation.

LS: Yes. This is the aspect but also the challenge that I’ve been pondering—working with the idea of autobiography to then subvert it in the production of the work. I feel like speaking about my autobiography is the strategy that helps me get closer to fully realizing and communicating my vision. I tend to speak more about my own past and present experiences because I find it less obstructive to other people. Because in one way, I can speak to being a second generation Chinese Indonesian, who had experienced persecution and was forced to leave the country. That is one way that I have chosen to say it. Another way to is to say that I come from a country that is predominantly Muslim, and in the face of opposition to a small percentage of outsiders, the Muslims or the natives feel that it is best to persecute this small number of people. I just feel like it gets too confusing when people have to hear that. And I have to contend with their understanding of Islam and power and immigration and family. So, for me, it’s a strategy to tell people, “Hey, this is what happened to me,” in hopes that they would empathize with me and check in with their own realities. We are not talking about Islam in general. We are not talking about capitalism in general. It’s more about my lived experience via a queer immigrant perspective. That is what I want to share. My autobiography is just a jumping off point.

ML: Another thing that I have heard you speak about in relation to some of your work is utopianism. The colors often seem celebratory or flamboyant even, taking full control of the space. Yet, often the space that you’re working in peeks through, as though you are balancing the celebratory aspect with the reality of what’s in front of the camera. You are also inserting things that are in your life or in your consciousness—outside of that room or within it. Like that of a fraught utopia, which is one of the hallmarks of camp. There is a sincere attempt to go all the way, but sometimes the distance between what is achievable on a human scale and what the imagination can conjure is an interesting distance. I feel like that is almost the engine of this work; the distance between what I might think I am looking at and what is actually there.

LS: It is so sweet to hear you say it. But also, it makes so much sense because truly, what I am after is the state of being content. It speaks so much about camp in terms of aiming to do something that is almost out of this world. Because of setbacks or because of the difficulties, it’s just so hard to achieve. At the same time, I do not want to be bogged down by it. I want to be able to dream as big and to also try as hard. Although I know, eventually, I have to settle with kind of a version of it.

ML: Well to me, that also is sort of the process of diplomacy. Where even on an international scale, we have these ideals of how people should treat each other. But diplomacy is a process of compromise that leads to a more complicated reality than the simplified ideas we might have of what is good or right. Your work provides no easy answers.