Right now, people are making images and uploading them to online image-sharing platforms such as social media at the rate of more than a trillion photographs each year. This number is so astounding that it’s worth pausing and thinking about for a moment: 1,000,000,000,000. If that number isn’t terrifying enough, consider that Americans devote an average of more than ten hours each day to screens, consuming a relentless deluge of images. How many images do we see daily? More importantly, how many of them do we really look at? How many do we remember?

Artists using photography are fighting a steep battle simply to get the public to sit with their work for longer than a few seconds. The context of a gallery or photobook might promote a sense of focus, but even then attention spans are embarrassingly short. Beyond the act of looking, I often wonder what makes a photograph persist longer in our personal or collective consciousness. On a basic level, what seems to make an image last for me has much to do with the intangible and unpredictable relationship between what I see and what I feel. Ultimately, a piece of art becomes whole because of the viewer’s cumulative experiences and perspective, because of what we bring to it. It has to move us in profound ways, emotionally or intellectually.

Of the hundreds of submissions, which included thousands of images, a surprising number did so move me, caused me to pause, look deeper, and just a bit longer. There were images that confused and confounded me, that gave me some kind of pleasure, that reminded me of a beautiful memory, that spoke to issues of social justice, personal identity, or politics, and images that simply shifted my perspective on the possibilities of photography. While there are many more artists that deserve to be highlighted than these three, I found the distinct visions of Samantha Box, Zora J. Murff, and Deana Pitzitelli to be compelling and lasting—therefore, deserving of the recognition of the Beth Block Honoraria.

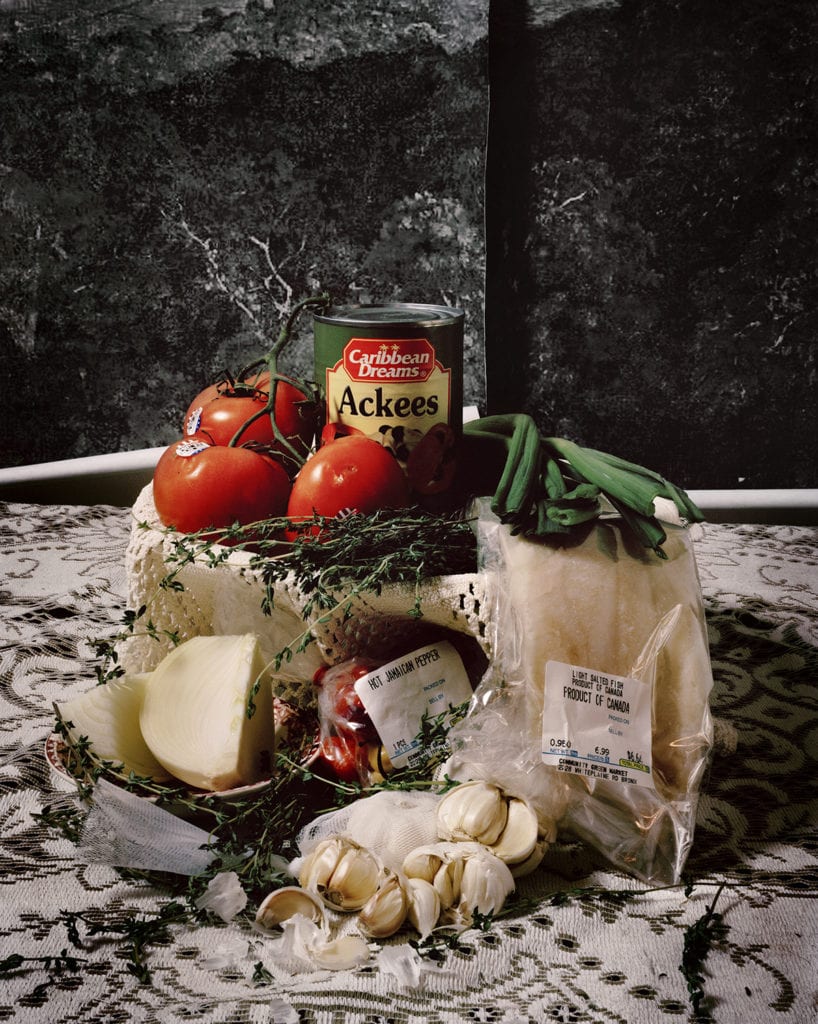

Jamaican-born and Bronx-based photographer Samantha Box’s Two Or Three Real Memories conveys complex personal feelings surrounding her own diasporic experience. A departure from her earlier documentary-driven photographs that tenderly looked at the lives of LGBTQ youth of color, her new work peers inward. Box contemplates how various iterations of self, “as a subject, rather than a colonized object, can exist simultaneously” and so be “questioned, broken down, and reclaimed.”

With a background as a social worker before working as a photographer, Zora J. Murff’s At No Point In Between takes a humanistic approach in understanding the “slow violence” of a systematic oppression that African-Americans have felt and continue to endure in America. Murff considers the effect of discriminatory housing policies, such as redlining, on the communities of North Omaha, Nebraska. Murff challenges the photograph’s use as an objective document, and that is precisely the power of his work—he brings viewers to a poignant space between the physical and the social, between the black body and the landscape.

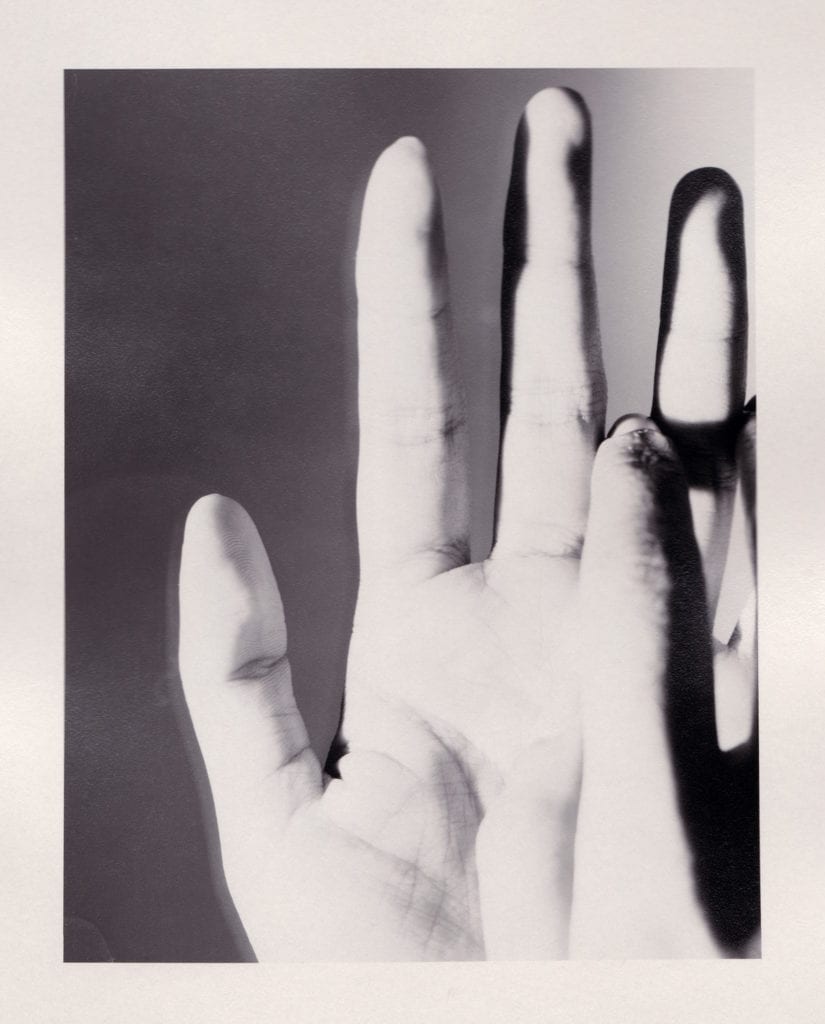

Deanna Pizzitelli uses images to test the possibilities of photographic language. Within her work, she brings together a variety of processes, papers, scales, and subjects. These highlight the materiality of the photograph and create what we might best call visual poems. She made Koža, the Slovak word for skin, during a period of travel away from her homeland of Canada. Together, the intimate photographs explore “the emotional landscape as it refers to desire, eroticism, longing, and loss.”

In different ways, Box, Murff, and Pizzitelli embody the potential of the photographic medium. Their work has the ability to take us away from the daily barrage of imagery for an extended moment and to move us profoundly.

Shane Lavalette

Director, Light Work