Ruth van Beek is not a photographer, but the feelings and logics of photography linger in her collage like stubborn specters. Photographs serve a utilitarian purpose outside of art contexts—they are images meant to be functionally interpreted. For van Beek, photographs are strange and beloved objects—she collects them, sorts them, arranges them, touches them. In the intimacy of this handling process, they develop a kind of autonomous life. In the conversation that follows, van Beek and I discuss her process and wonder together about the meaning it creates.

Jessi DiTillio: Your work uses found images from an eclectic range of sources, like old photobooks, flower-arranging magazines and manuals, scraps of painted paper, and more. What role does the collection process play in your work? Does the source of the original image matter to the piece, even if it is not visible, or hard to identify in the final artwork?

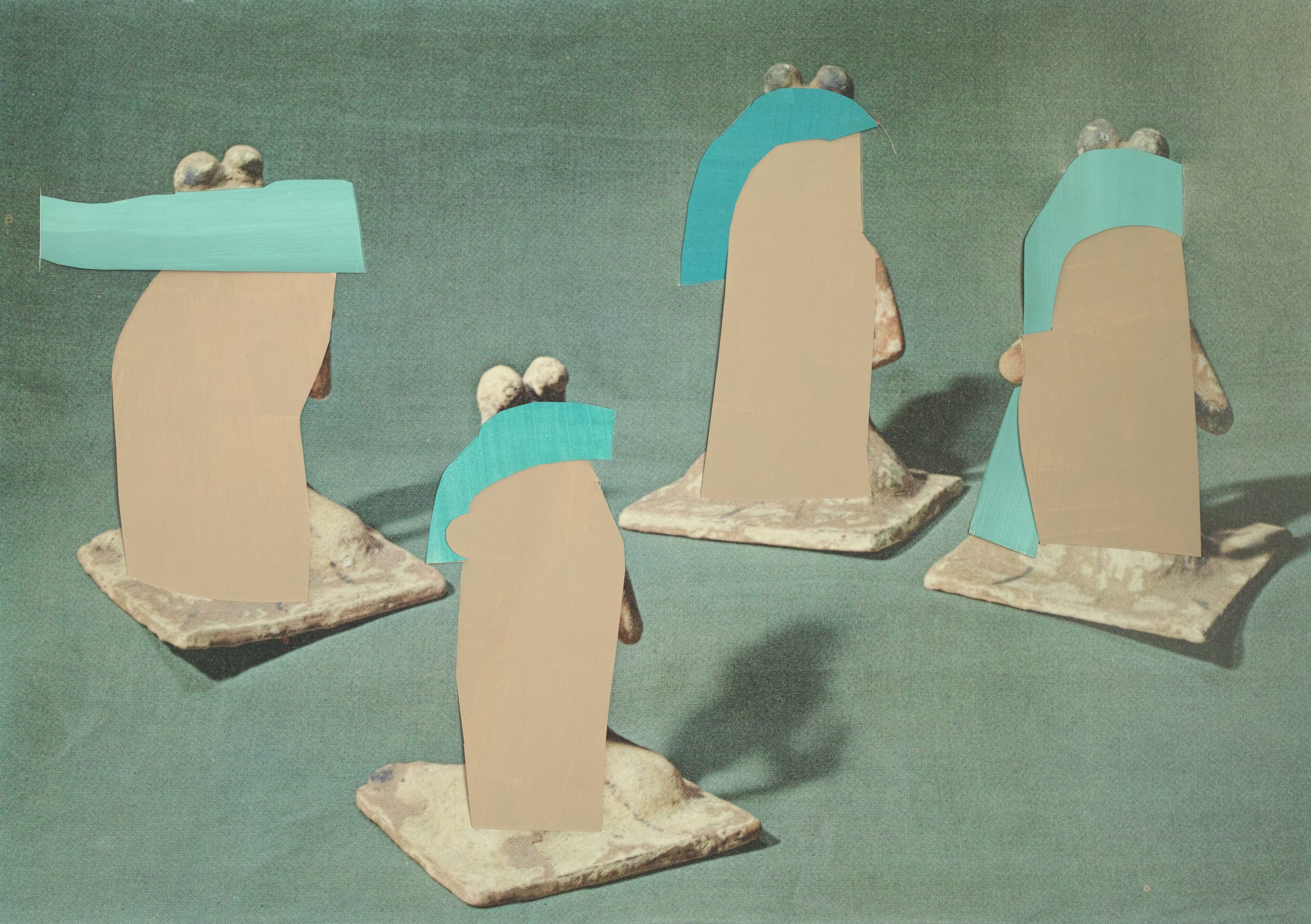

Ruth van Beek: The archive I have built is the basis of my work—I always start with collecting images. I go to second-hand stores every week, find books I like, take them home, and cut out all interesting images. Many of the books I buy are books for around the house; they are pre-internet information carriers. They were made to teach us something, to show us how to do things, how to cook, how to take care of your plants, how to hang the curtains. But I also use many books about art, archeology, and travelling, books that show us the exotic worlds of treasures and history, that were made to trigger the imagination.

I take the images from these books out of their original context, but their origin is still in their DNA and therefore also present in the final work.

JD: You seem to be drawn to “useful” images—do you think your process of working with them undermines their use value?

RVB: Yes, many of these “useful” images come from instruction manuals. In them you see hands showing how to do things. But when taken out of their original context, these hands become more than simply explainers. They are also my hands and function as a self-portrait within the work. The hands become activators of the silent objects. Their touching, pinching, and caring help the viewer to understand the material. So, my process does not undermine their function, but gives new direction to the image.

JD: Much of your work deals with animation, or in other words, with bringing things to life that we don’t expect to see as living.

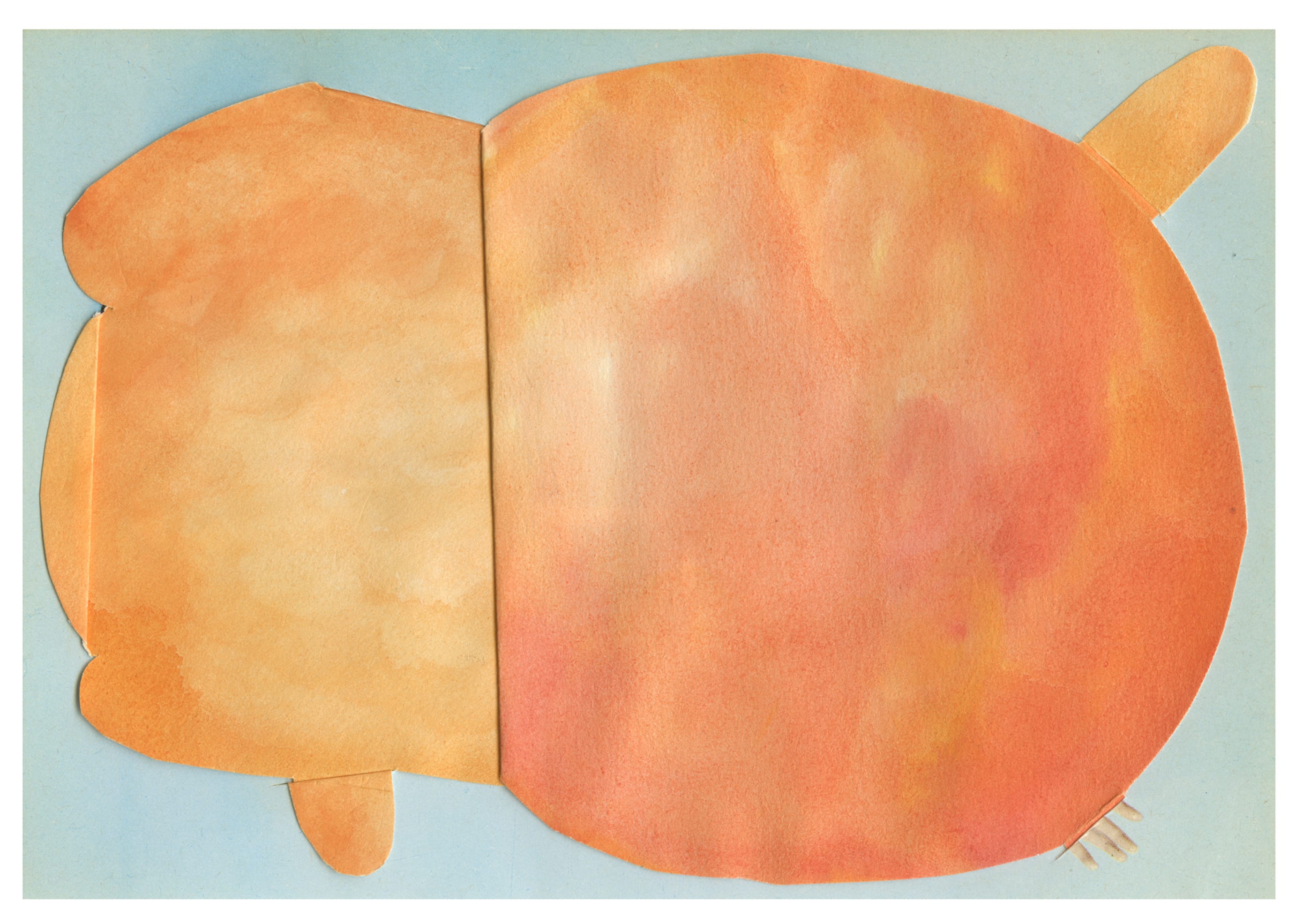

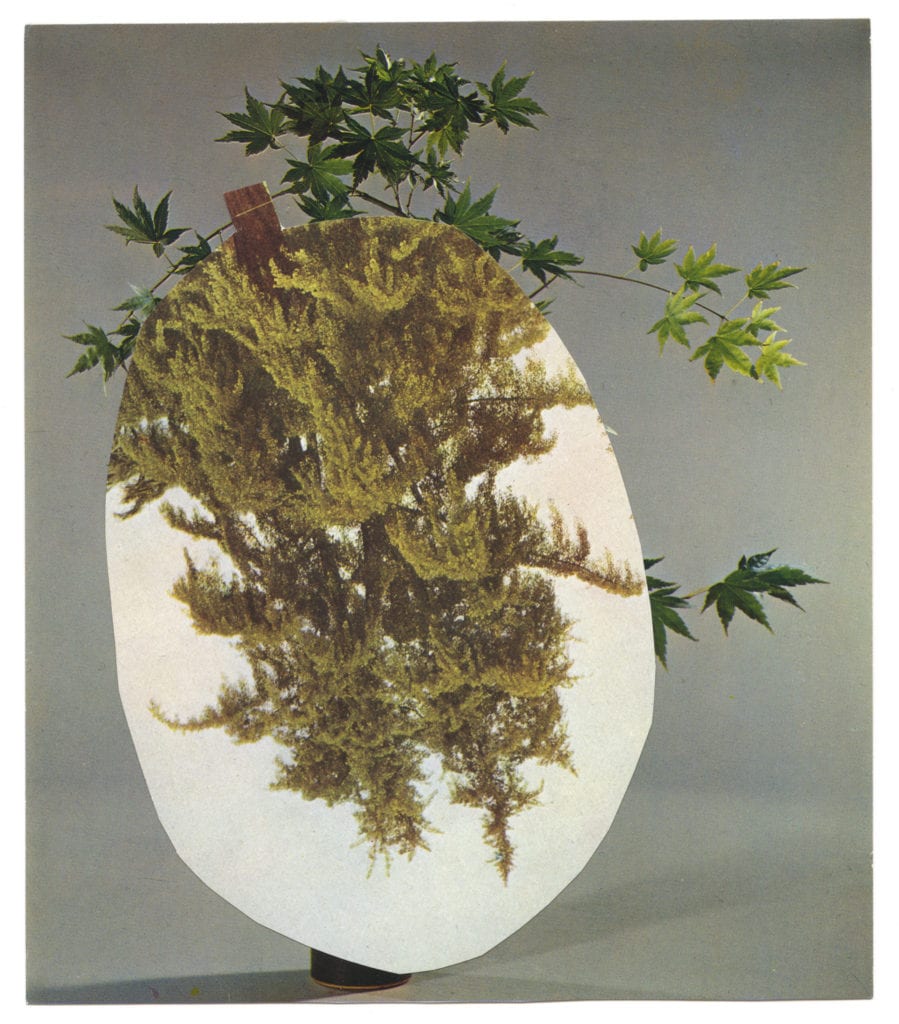

RVB: When I was working on the series The Arrangement, a series with its origin in flower-arranging manuals, I started to notice this quality within my collages. For me, they transcended their abstract color and shape and became full of life; they were growing and leaving the frame.

When I make a collage, there is always a moment when the work is finished. That moment is very clear to me; it is the moment when the image in front of me becomes a figure that can stand on its own. That is, it becomes autonomous, and speaks back to me.

This became more and more a theme in my work. My recent works are always bringing abstract figures to life. I’m interested in how the viewer animates them with their gaze. They fill in the missing pieces by starting to relate to them. I like that you can see both the simplicity of the construction, and at the same time have very strong feelings towards the figure, as if it were a living being.

JD: You often play with gravity, creating a startling or disorienting sense of space, particularly in the series The Levitators. Does levitation play a symbolic role?

RVB: I think about gravity a lot in my collages. You often find important details at the bottom of the image in the “feet” of the object. Where and how it touches the ground says something about the weight of the figure.

For me, levitation has to do with trying genuinely hard and failing. The work is about exercising, repetition, and of course, the secret life of dogs…

When I think about it now, flying has always attracted me—airplanes and the impossibility of them. They have a resemblance to a body, and when they are on the ground, they lie down, heavy like a stranded whale.

JD: Is your approach different depending on the source material you’re working with, like dogs versus flowers?

RVB: Not always, not intentionally, I think. I do like the fact that dogs or other small animals are made by humans to meet our aesthetic needs. Like flowers. It is about bending nature, manipulating it in a way that we prefer it to look. You could say that idea of bending nature is in the heart of my collaging. And that is also the place where the material and the way I use it meet.

JD: I think one of the things that is fascinating about our relationships with both dogs and houseplants is that they are living creatures that we communicate with (or try to) without language. There is some kind of pure pleasure in successfully caring for a living thing through intuition rather than instruction. Is that something that resonates with your work?

RVB: Yes, that’s interesting, I never thought about it that way. The work process is without language and therefore more intuitive. But yes, I think intuition is a very important element within my work process.

My archive is stored in boxes with categories that change quite often. It would be useless if I stored it with a logical system. I spend a great deal of my time looking through the piles of images and this process loads the images in my head, so they form a subconsciousness.

Next to the collected image archive, I have been making a shadow archive of color shapes. Once in a while I plan a day for painting the colors. When the paper is dry, I cut out shapes, turning the paintings into objects that I can use. Both these processes are almost completely without language.

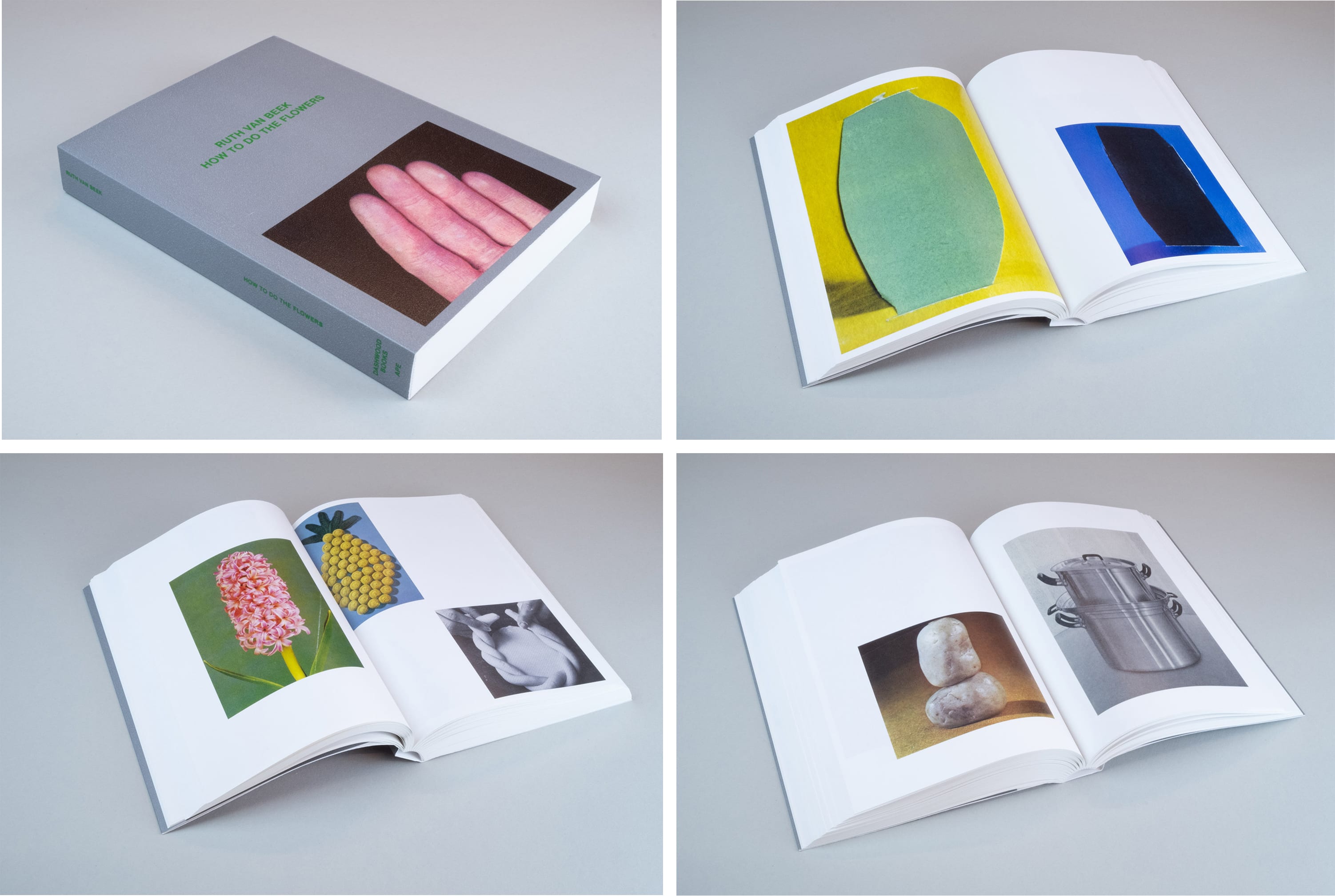

JD: You clearly enjoy publishing your work in a photobook format. How do you approach sequencing your images? What does the book form do for your work?

RVB: Image language becomes really present when different images are brought together. On their own, the works only speak about themselves and are sometimes hard to read. But in each other’s company their mysterious language becomes clearer. They influence each other, they start to shake and provoke doubt about what they are. This is where it becomes interesting for me.

The stories of my work arise from this strange language, but I am the director of the play. I am the one who says “cut” and decides where to freeze time. When I make a collage, I am searching for the decisive moment where everything falls together into an image of something that never existed before.

A book is the perfect space to practice this, but also has its own logic as an object. I like to play with the expectations of a book—you hold it in your hands and see how heavy it is, how it feels, how you look through the pages. Do you start in the back? Do you quickly flip through or treat the book as a holy thing?

My latest book, How to Do the Flowers, includes hundreds of images from manuals and also studies for my collages in unexpected combinations. They provide the viewer with context for the collages, reveal the underlying work process and at the same time compose a personal guide for making new work. The title of the book is a reference to the origin of large parts of the archive. It encompasses books about housekeeping, books that explain to us how to live, how to do the garden, arrange flowers, or hang the curtains.

“How to do the flowers” is a question but at the same time a restriction. It should be done this way and no other way—a compelling set of guidelines doomed to be violated and therefore produce failures.

JD: Could you talk a little more about how you use titles? I love your series titled The Situation Room, in which the title gives a much more concrete clue about how to read what could otherwise be very abstract or ambivalent images. That title prompts me to think about the very subtle clues of self-presentation and dress that produce a political subject.

RVB: The title The Situation Room was also the title of an exhibition I did in Amsterdam in 2016. I was playing with the gallery space, which had a big table in the middle where people would work. There would be meetings in the room during my exhibition. I imagined that the figures in my works were also present in the room, discussing things, having a meeting.

And then I also thought about the Situation Room in the White House, where things are being decided and talked about while we are living our lives. I like this “doubleness” in the title. It is about a situation in a room and about world politics and our disconnection from that.

For me, a title is a key to how to read the work and connects it also to the world of language, to the human world. I don’t think I would ever make a very direct political work, but I am in this world, and the information I take in from daily life and news will find a way through in the works I make and come out in a more distorted way. Like with theatre or carnival, artwork can be a laughing mirror, a looking glass.