I’ve had the strange feeling lately that I’m growing.

Not quite “up,” as the arboreal saying goes, but somewhere something is stirring. It’s a nagging distractedness and a pleasurable one at that. I don’t mind it, figuratively or literally. In fact, if I have any issue, it is the recurring notion that perhaps I should mind it. A daily astrology account that I follow suggested, when the moon was in Capricorn, that Capricorns grow YOUNGER as they grow older. We have to learn how to play. I don’t think I was a serious child; I guess you’d have to ask my mother. But perhaps I did not play enough in my youth—a youth that for a woman such as myself (white, middle-class, perhaps overly educated), can now easily extend beyond the twenties. This might not seem ideal timing to be learning to relish spontaneity and curiosity, when responsibilities of and for the world come calling.

But what better way to meet the unsure possibilities ahead than with the suppleness that comes from knowing you, too, are shifting, growing.

_______________________________________________________________________

As I work, I periodically get distracted by the birds searching for lawn grubs in the backyard. (My desk faces out on a wall of twelve-pane windows, for better or worse. Typically for the better; I’ve come to consider the mental drift encouraged by this gridded view a necessary part of the work.) I should say, on this day, there are not only birds, but also squirrels. The latter would normally interest me more—something about their twitchiness and those improbably tiny, capable hands. But today the birds hold my attention because they are so many: dusty grey doves, iridescent black starlings, and a few cardinals all tucked in together, pecking away. To be honest though, I am drawn into this scene not simply for what it is, but also for what it could be. It strikes me today, through the window panes, as an empty image, relentlessly full of potential.

Some people have found it helpful to frame the photograph and the photographic process in terms of semiotics. While I don’t tend to take these approaches too seriously, I can find some fun in the morphological matching game they play: similarity—when things are precisely not the same—can illuminate difference. What follows is a summary of the chapter entitled, “The Nature of Pronouns,” from Émile Benveniste’s Problems in General Linguistics (translated to English from the original French in 1971). You can do some matching, if you so please.

First- and second-person pronouns (i.e. I/you), indeed all “pronomial forms” except the third-person (e.g. this, here, now, today, verb tenses) have no set referent. They are filled only in the “instance of discourse,” when the words are spoken or read. These forms, therefore, do not refer to reality, as such, or to “objective” positions in space or time, but rather to the utterance, unique each time, that contains them. In that sense, “pronomial forms” are not subject to the condition of “truth” as it is conventionally understood. In fact, they make clear that language is not a system of signs so much as an act, an activity of appropriating language. They also make intersubjective communication possible.

Yesterday I visited the wild parakeet colony near my house, as I often do when I feel out of sorts. These are highly social creatures, who build enormous stick nests along power transformers and tree branches. I have heard that they mate for life and, what’s more, that each pair lives in a single compartment of the honeycomb-like nest with several other pairs. The fact that these birds are all nearly identical only adds to the magic of their communal living for me. Both males and females have large heads, grey bellies, green backs, blue underwings, and long, fringed tails. A parakeet flies in with sticks or food, enters the nest, and comes back out to repair damage or chat with others or warn me off when I get too close. But from my vantage on the ground, it’s never quite clear if the bird I follow into the nest is the same one that exits. This is what I find so thrilling about watching them: they resist being definitively known, particularized. Although clearly discrete birds, they remain an emergent group—not generalized as an indistinguishable mass, but still abstract. This is, I suppose, not an uncommon relation to feel with or toward groups of animals in the wild. But watching the parakeets’ blue-green-grey wingspans form the most elegant of crescent shapes, I am reminded of all those other instances of impenetrability and feel strangely comforted.

_______________________________________________________________________

You asked me what I was thinking, as if you didn’t already know:

Well, Radclyffe Hall, for one. And her dachshunds.

Yep.

The oceans, getting larger and warmer by the day.

Right.

And we still don’t know what pictures want.

Mmm…

As we walked on, in a comfortable quiet, I took note of two, new-to-me freckles on your left arm. I’d have to reconceive that particular constellation. It was now less Venus di Milo and more Statue of Liberty…? Meanwhile, you pressed for more.

But are you okay?

I’m pretty content right now. Are you—

Yeah.

Usually, I am more than happy to give you more. It’s the least I can do. But I had become preoccupied by the memory of a particular picture. It was almost certainly a picture you didn’t know, and I wasn’t sure I could capture it for you—not in a Barthes’ mother kind of way, its essence ever-escaping me, but because I was having a hard time remembering the picture at all. There was a white beach in bright, even sunlight. The view, I thought, was through an architectural feature of some kind, maybe a window. All was very…flat. Yes, the overwhelming memory I had in that moment was the collapsing of space, that flatness. I hadn’t thought about it in a long time. Why now? What did it want?

Mmm?

_______________________________________________________________________

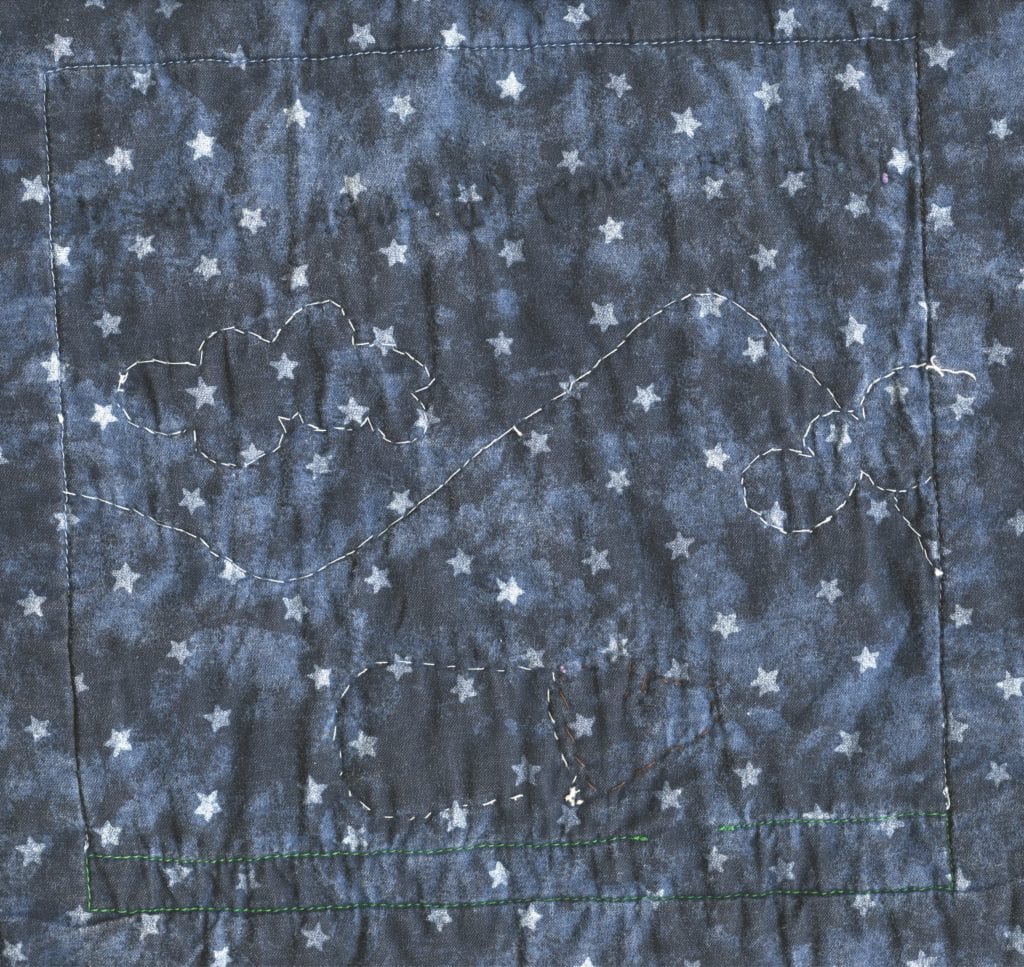

Stars are signals. To look up at the night sky, is to look back—not at the stars themselves, but at light emanating from moments long, indeed, inconceivably gone.

_______________________________________________________________________

George Kubler, a twentieth-century historian of ancient Mesoamerican art, believed art objects are like stars. For those willing to gaze, the aesthetic form of each object can transmit something of its previous moment, something that will be “still valid in actual experience” in the present. In The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (1962), Kubler argues that art’s signals answer specific needs and problems concerning emotional experience. This “functionality” of forms is not often valued as such in my society, nor was it in Kubler’s. In fact, similar to what we divine in the stars, whether and how an art object reverberates in the present depends on perception, on which parts and pieces the viewer is able or willing to see in that moment. But Kubler felt strongly that art itself could help to expand perception, making way for the realization and acceptance of new and other forms of knowledge. To sense signal-shapes across time, their repetitions and their stuttering alterations, is to trace needs, problems, affects: “As the linked solutions accumulate, the contours of a quest by several persons are disclosed, a quest in search of forms enlarging the domain of aesthetic discourse, [a domain that] concerns affective states of being…Aesthetic inventions expand the range of human perceptions by enlarging the channels of emotional discourse.”

I’ve had the strange feeling lately that I’m growing.

_______________________________________________________________________

Text by Francesca Balboni

Images in order of appearance:

Anika Steppe, Untitled (Elephant), 2018

Anika Steppe, Untitled from series “Lily”, 2016

Anika Steppe, Untitled from series “Lily”, 2016

Anika Steppe, Untitled, 2016

Anika Steppe, Pishr of Davy from series “Stars and Flars”

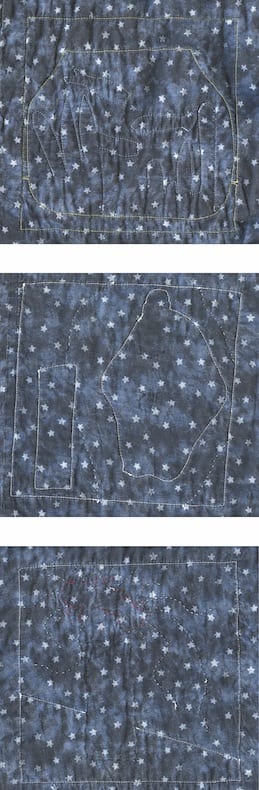

Anika Steppe, Fish; Snowman and bookmark; Starting to think about perspective all from “Stars and Flars” series, 2019

Anika Steppe, Flowers and Stars, 2019