“Step forward a little so we can see you.”

Roland Barthes evokes a scene at the end of a bridge in a glassed conservatory, or winter garden, where a photographer poses a brother and his younger sister, a five-year-old girl who will grow up to be Barthes’ mother. She stands a little back, facing the camera, and Barthes senses that the photographer must have tried to coax her forward. This “anonymous provincial photographer” and “indifferent mediator,” who “did not know that what he was making permanent was the truth,” then disappears under the verdant fecundity of the garden. There is no reason to remain. The photographer is not part of Barthes’ narrative of finding, in this faded photograph, “what constituted that thread which drew me toward photography.” In this essay, however, I invite the photographer to step forward into the light, if only for a moment.

The anonymous photographer of the Winter Garden Photograph is not the only absent photographer in Camera Lucida, a theoretical treatise on photography or an act of mourning for Barthes’ mother or both. Intending to limit his “Reflections” to his own experience, and lacking any as a photographer, Barthes “could not join the troupe of those (the majority) who deal with Photography-according–to-the-Photographer.” But Barthes does mention photographers frequently, and what he says suggests that he does not merely avoid speaking from their point of view but rather that he carefully sutures over their role.

One means by which he does so is to conflate the photographer and the apparatus. Before eliminating the photographer as a subject, Barthes speculates that the emotion of the photographer has to do with looking through the “little hole” (stenope). Stenope might seem a surprising choice because the word designates a small hole that substitutes for a lens in the camera obscura. Viewfinder, in French, is viseur. But perhaps it is not surprising, because elsewhere Barthes conflates the lens with the photographer. To be photographed, for Barthes, is to “feel myself observed by the lens,” not by the observer behind the lens. Photographers, to Barthes, are dominated by mechanics; the ones who transcend mechanics are “great photographers,” those who can make something even of a polaroid, for example. But once mechanics are transcended, he says little about what makes a Nadar or an Avedon great.

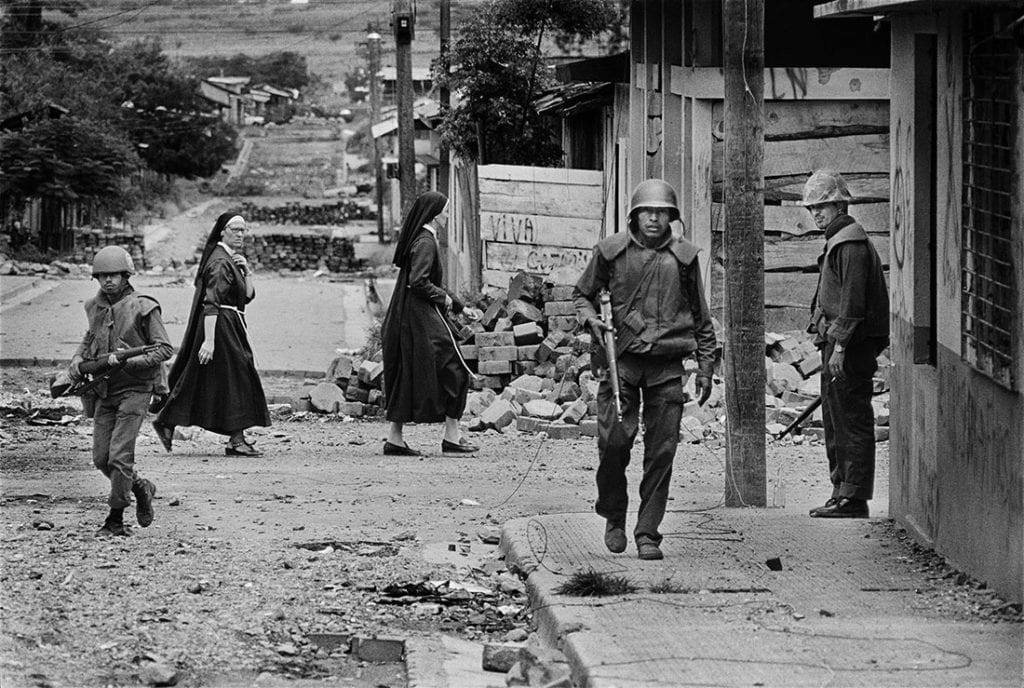

Another way in which Barthes brackets the photographer is to contend that, great or not, he never appreciates the oeuvre of a photographer, only individual photographs. Hence, as many have noted, it is not the subjectivity of the photographer that interests him, only his own. And the “punctum” for Barthes, which makes a photograph “live for [him],” must be a detail: something accidental that “happened to be there,” which the photographer might not notice but “could not not photograph” (47). Not only was the Winter Garden Photographer ignorant of the truth, the power, of his picture, but seemingly Koen Wessing, when he photographed Nicaraguan soldiers (fig. 1). The nuns “‘happened to be there,’” passing in the background (43). It is as though soldiers were Wessing’s subjects, not nuns and soldiers, that Wessing did not judge the very space and the moment when the nuns would appear and when the choreography of movements and glances between the three soldiers and the two nuns, and even the photographer (most of the subjects look at him) would coalesce in a composition to convey, disturbingly, the dissonance – if it is dissonance – of the situation.

Sometimes the punctum is not a detail, but rather time itself. Time has even less to do with the photographer, who, like the subject and the photograph itself, is at the mercy of time. This punctum conveys the “that has been,” that Barthes identifies as central to mourning and that depends on photography’s claim to represent “reality.” The subject of mourning returns us to the Winter Garden, and to one motivation for writing the photographer out of the discussion.

His mother’s kindness, “the kindness which had formed her being immediately and forever,” emanates from the photograph. Her kindness is sealed into her appearance like the freshness of the vegetables tumbling out of a net bag in another essay by Barthes; the girl is as unselfconscious as one of the vegetables. I have written elsewhere that such essential kindness is not literally photographable. But it is also true that the quality kindness does not exist in isolation. A kind person is usually kind to someone; at least, for kindness to show, something must evoke it or make it visible. The photographer’s request suggests an interaction may be at stake: come join us. That the request might not have been made changes nothing. By ascribing it to a photographer, Barthes showed that he understood something of the interaction at the core of a family photograph, someone posed it so that the family could relate to it.

What if, then, instead of “interaction,” we use the word “relationship”? Barthes declares his love for photographs whose subject meets his gaze. In such cases, Barthes writes, citing André Kertész’s photograph of a boy with a small dog, the subject “is looking at nothing.” (fig. 2) Yet, here the photographer is absent just where one might expect to encounter him, for surely the boy was looking at Kertész. In Kertész’s absence, however, the photograph and everyone in it remains alone with the spectator. This solitude is especially true of the little girl in the Winter Garden Photograph. Not only is she by herself throughout the book, once the photographer has left, but even her brother, who inhabits the photograph with her, vanishes in Barthes’ account.

It has been suggested that Barthes, author of the essay “the death of the Author,” was motivated to bracket the photographer as he bracketed the writer, in order to make clear that the work, not the subjectivity of the author is the focus of the reader’s attention. This may be true. Yet an interest in the photographer’s role does not have to mean an interest in her subjectivity. It may mean the recognition of the photograph as the embodiment of a relationship of the photographer to the subject, as the form or performance of such a relationship, or as a form of attention that may or may not have been returned. Although the subject gazing in my direction does not look at me, the spectator, the subject is not “looking at nothing.” The subject is looking at a photographer, and this relationship is embodied, imagined, in the photograph. The photographer, then, is the ladder Barthes climbs to renew his relationship with his mother. The future mother and the photographer together produced a relationship, and then the photographer left.

I expand on the photographer’s request: “Step forward a little so that we, your future son and I, can see you.”

Sources

Roland Barthes, “The Rhetoric of the Image”, Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 32-51.

Margaret Olin, Touching Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012),

Roland Barthes, “Death of the Author,” Image, Music Text, 142-148. Michael Fried sees in Camera Lucida something of the movement toward anti-theatricality that he chronicled, in “Barthes’s `Punctum’,” Critical Inquiry 31 (Spring 2005): 539-74. But see also Vered Maimon’s cogent reservations in ‘Michael Fried’s Modernist Theory of Photography’, History of Photography 34 (2010): 387-395.