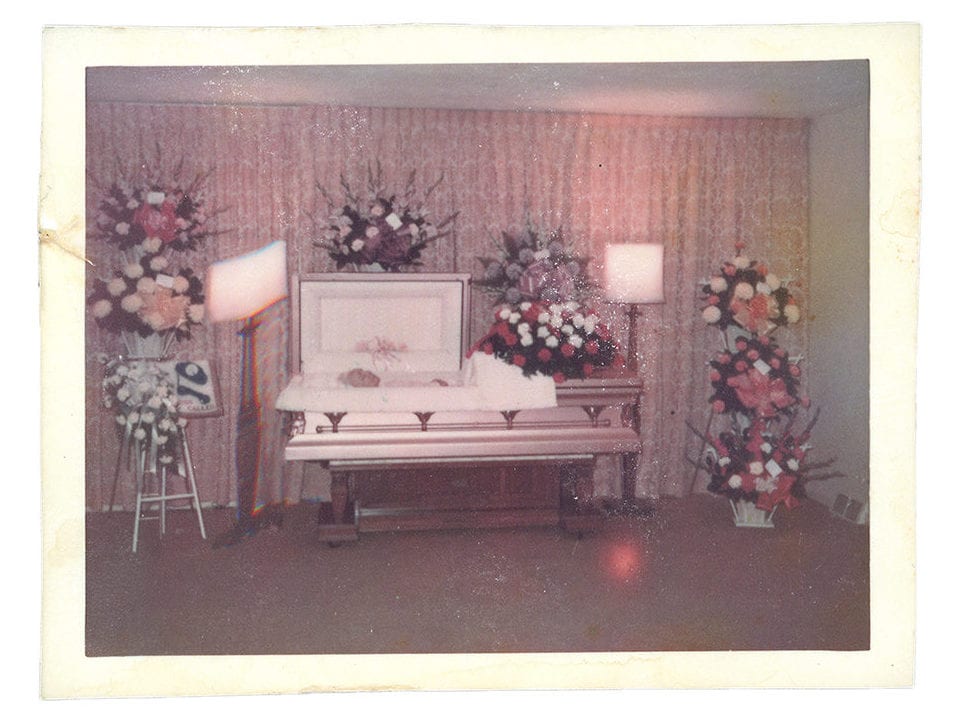

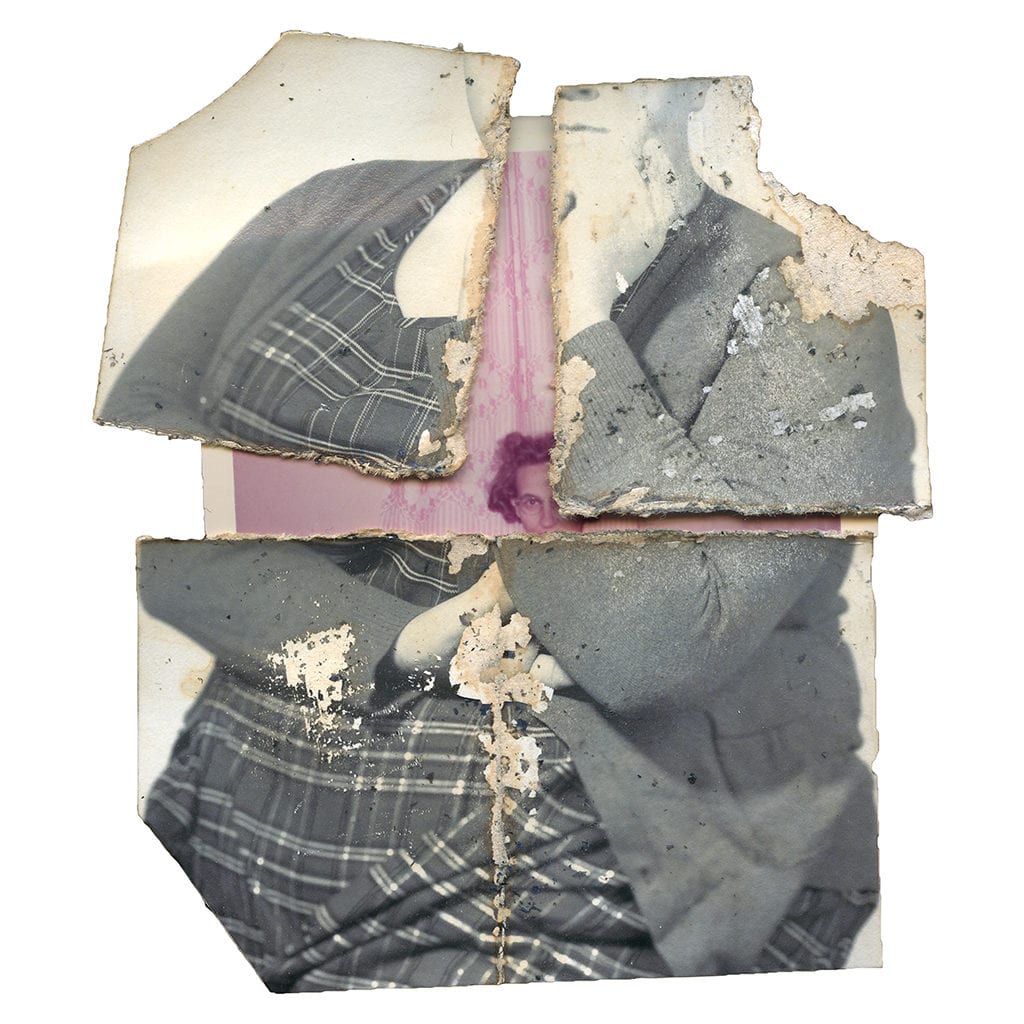

Victoria Ridway’s series, Patrimony, is an exploration of her father’s family photo archive. Throughout this series, she scans, manipulates, recreates, and layers the archival images to reinterpret her family’s history. Utilizing self-portraiture, she reinserts her Aunt Bernice, an aunt by marriage that Ridgway’s grandmother had previously removed from the family story. This reinsertion into their visual narrative allows her to confront her ancestors and disrupt the generational trauma that the family has been avoiding. Through collage and combining contemporary and archival images, Ridgway shows her family members within herself, literally revealing ancestors underneath torn images of her own form, thereby solidifying the idea that we are made up of everyone that came before us. This work opens up a conversation about the inheritance of trauma and the manifestation of pain.

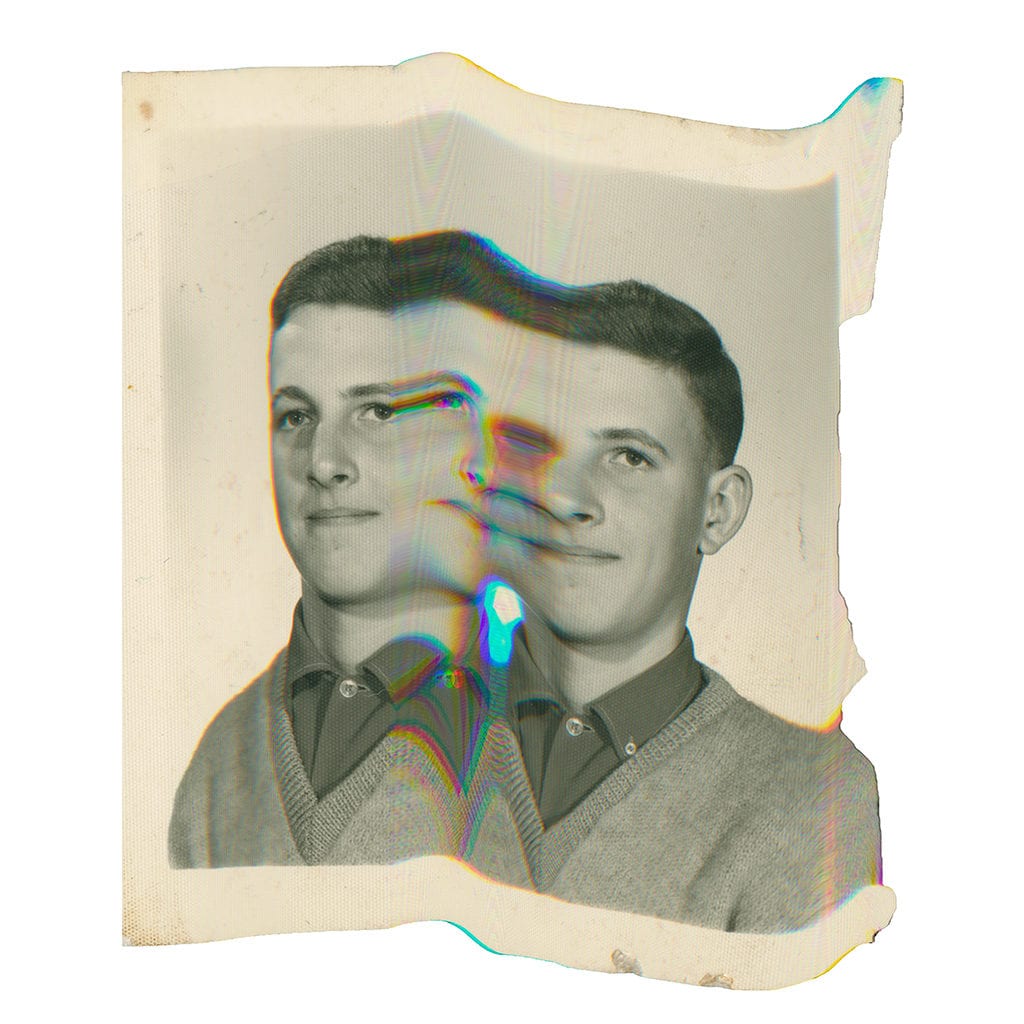

The archive she has created is a reflection of the intangible quality of memory. Peering into images such as Richard or Delia is like staring into the surface of water, trying to recognize a solid image in something that won’t stay still. There are fluctuations and instability. These photographs are of a time that is neither in the past or the present. They come from a place that is both unreal and familiar. It is because of these dualities that the images shatter and spook me.

Where does this work fall for you on the spectrum of truth and fiction?

These images straddle fiction and truth. They are based on folklore, the idea of a myth, and familial storytelling. For example, imagine a family member who died long ago. Maybe your parent or grandparent knew them. They died before you were born. The only way you know that person is through stories and folklore that people have told you. You may have an idea of how their portrait looks. However, when you go back into the archive and actually see pictures of them, you start putting on filters about who you think they really are and the memory that has been handed down to you. The thing about memory is that it has been manipulated every time you think about it because you are romanticizing it or adding some fiction somehow. That’s how I feel about these familial stories I’ve been told. They are reality-based but romanticized—no trace of abuse or repercussions for violent acts or words.

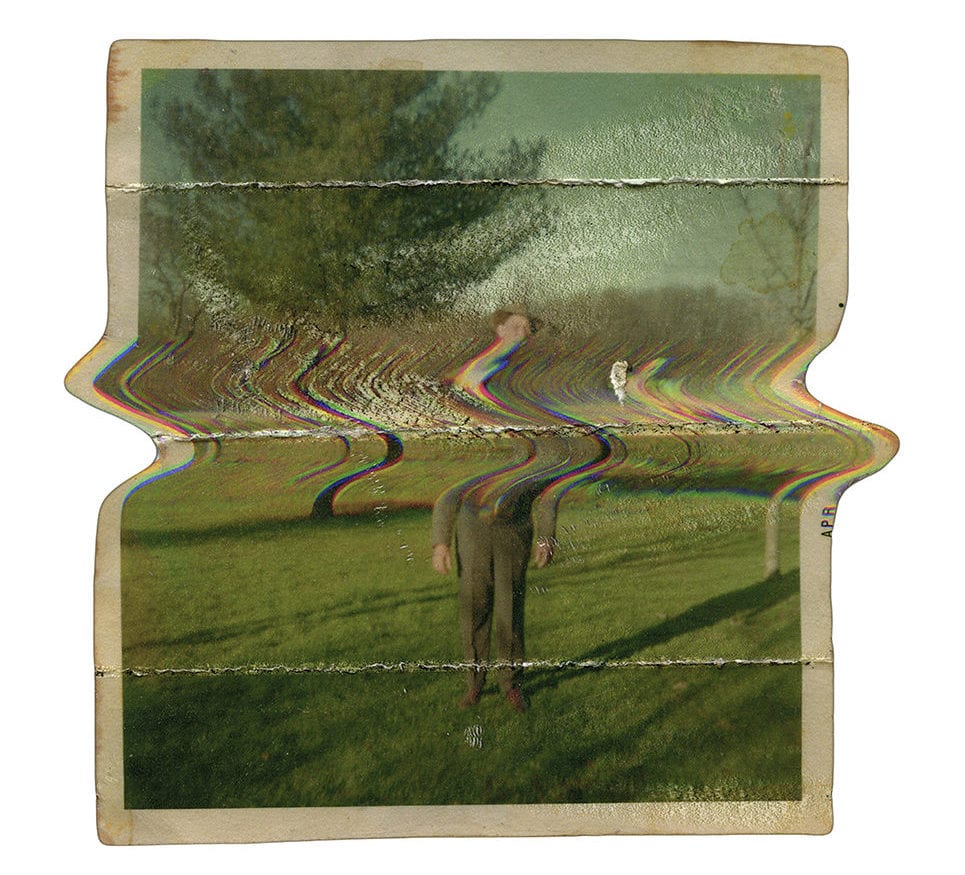

One of the first images I created for this body of work, Walter + The Farm, features my grandfather. He was beloved, but I often wondered how much of his memory was idealized, because he died a tragic death at sixty-nine. My dad was eleven years old when his father died, and so he sees him through the eyes of a child; he doesn’t see him through the eyes of an adult. When I created the Walter + The Farm image, I felt as though I could honestly see my grandfather for the first time. He was no longer a dissolved memory but was fully manifested.

Your other bodies of work are about womanhood and the body. How does your womanhood influence your relationship with your family archive? Do you feel a sense of responsibility to your ancestors as you work with these images?

My grandmother was the one that put this archive together. She created most of the images, and all of the books are a collection of things she gathered to record our family. I’ve always felt I was the next generation, the record keeper of the family. I hold a lot of responsibility for making sure those images are alive and that they are in a safe space; that they are looked at often. I am a bit of a hoarder in that aspect, I think, and that is one of the many reasons I have gone through and found specific images to recreate them or to put my own filter on them. I don’t want to give them up or separate them by giving them to family members. This archive was originally curated by my grandmother to remove some family members and show the movement of time. My goal is not to destroy her fingerprints but to uncover the truth and create my own space for that truth to live in.

There are many physical and temporal layers happening in this work. How are you using your body to reinsert yourself and your aunt, Bernice, into this narrative? There are a number of photos where I see your face. Are these images of you or of someone else?

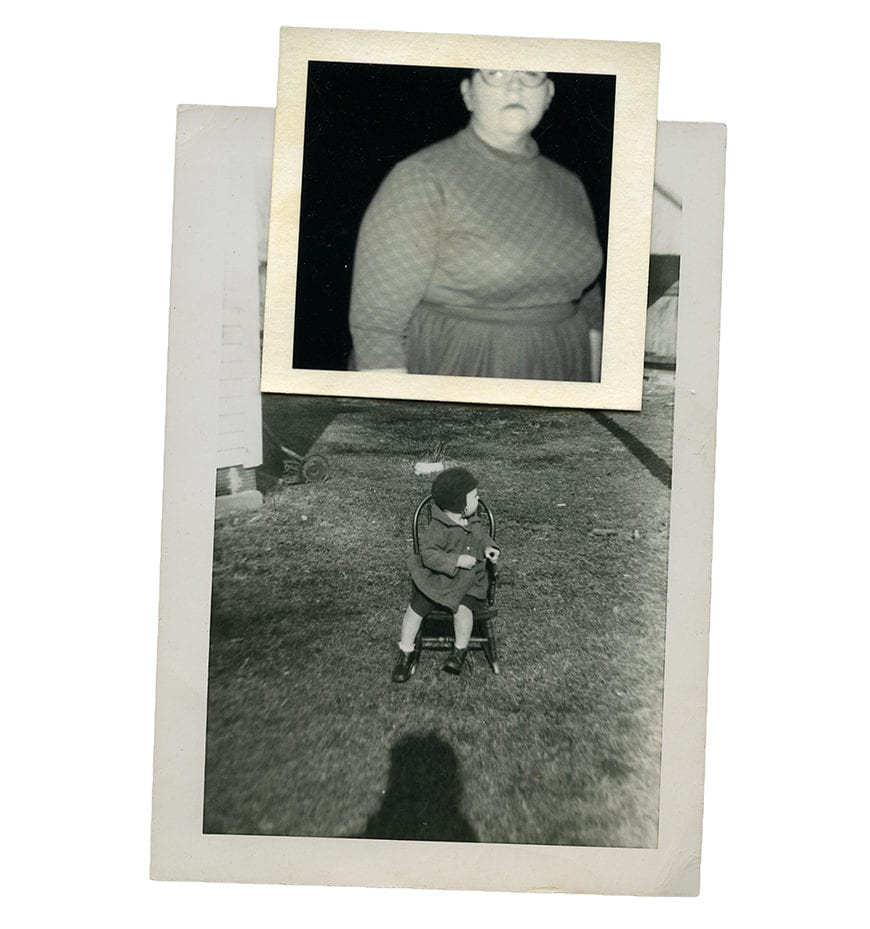

There is a duality, in a sense, that I am playing a character. I am reinserting my aunt into the archive, but I’m not taking away so much of myself for it to be completely transformed. I had not seen a picture of her until about six months ago when I discovered her existence through researching my family tree. I am also highlighting myself as a fat-bodied person because the manifestation of this abuse and generational trauma shows up in my body type and in the idea that I am obese-bodied because of things that happened that are beyond me. This isn’t something that is new in theories around bodies and body types. We do not have a clean slate when we are born. The narrative is much more complicated and has more to do with our genetics, experiences, and inheritance of complicated coding.

Is there an image in this series that gives you a sense of closure from this family trauma?

The image that I have the strongest connection to is Rivals because of the duality of Bernice and me. This image is essential when we talk about Bernice and her erasure from the archive. It shows the tension and anger between the two family members. The bottom image is of my grandmother, and you can’t see it, but in the image itself, she is holding my dad. She is holding a baby, but the way I have layered this image on top, her expression and body language has been completely transformed. The resulting image is more of who my grandmother was to me—this kind of questionable person. This image not only allows space for Bernice and my grandmother to have a conversation but also for my grandmother and me. Though I love her, there is trauma there. This image is not only showing a fat-bodied person. It can be interpreted as a judgment of a body or a fight between two people.

While all of these images become digitized at different stages of your processing, the final pieces aren’t finished until they are created as pieces that could exist in an actual archive, as objects outside of the digital realm. Why is touch and physicality important to this body of work?

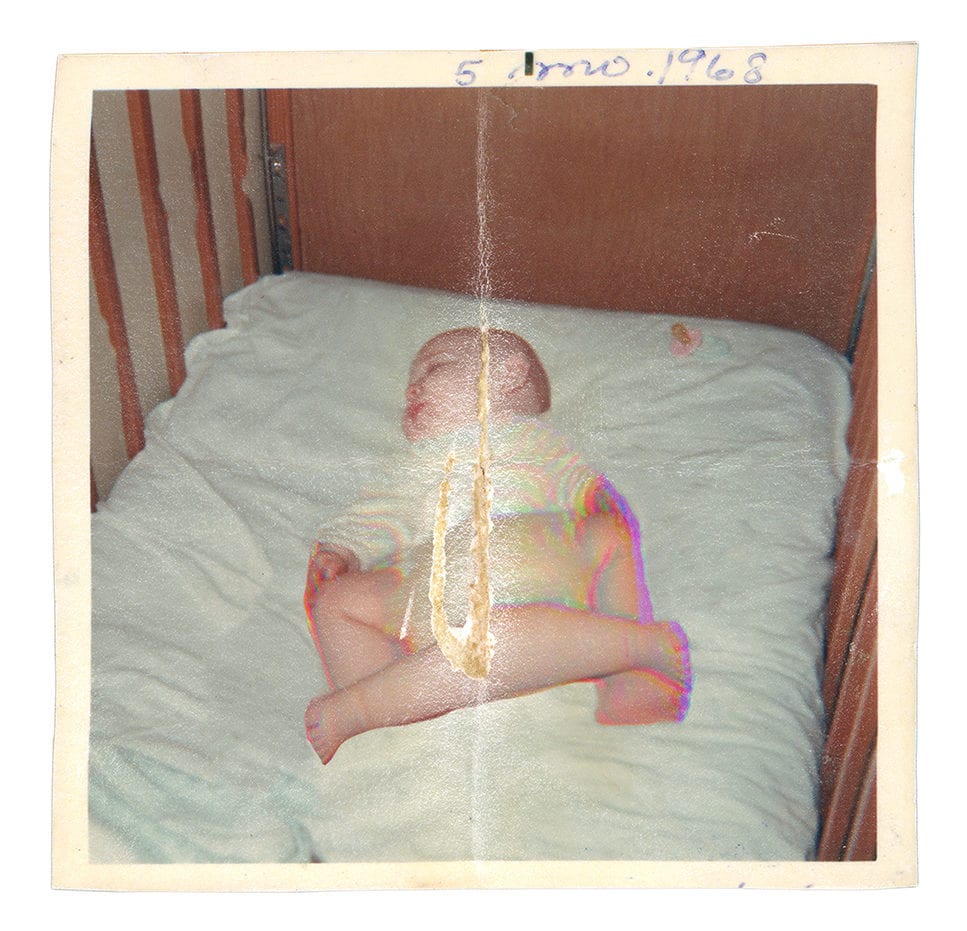

These images are touched in many ways. They have either touched the inside of a photobook, so they are stained because they weren’t in an acid-free environment or folded up inside a wallet. They’ve been in their environment for so long and loved that they are falling apart. Even though that looks violent, it’s much like a memory being manipulated every time you think of it: aging, the touch of age to show the sandwiching of time and presence.

Where do you see these physical objects going after you die?

That is THE question! I have no idea. All I can do is hope and speculate. Maybe if I have children, they will get passed down to them or end up with a loved one. Who honestly knows? Do you know what would be badass? If, when I die, my images end up in a flea market, in a pile of photographs, being sold for 50 cents, with only the text written on the back to explain their origin.

About the artist

Victoria Ridgway is an Indiana and Louisiana based Photographer. She received her MFA from Indiana University – Bloomington in 2019 and was a recent Assistant Professor at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. Her work examines power structures in representation with a particular focus on Fat bodies, the spaces/roles they are denied access to, and the urban legend of the Obesity epidemic. Ridgway is a 2019 Alumna of Review Santa Fe. She was awarded an Honorable mention from the 2017 Tokyo International Foto Awards and was a finalist for the International Photography Annual 7 at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, Ohio.